Madame Yevonde

Madame Yevonde, In Camera, London, John Gifford, 1940

→Salway Kate, Goddesses & Others. Yevonde: A Portrait, London, Balcony, 1990

→Rogers Brett, Madame Yevonde: Be Original or Die, London, The British Council Visual Arts Publications, 1998

Goddesses and Others: Photographs by Madame Yevonde, National Portrait Gallery, London, 17 January–30 May 2005

→Madame Yevonde, Be Original or Die, Kulturhuset, Stockholm, 19 March–29 May 2005

British photographer.

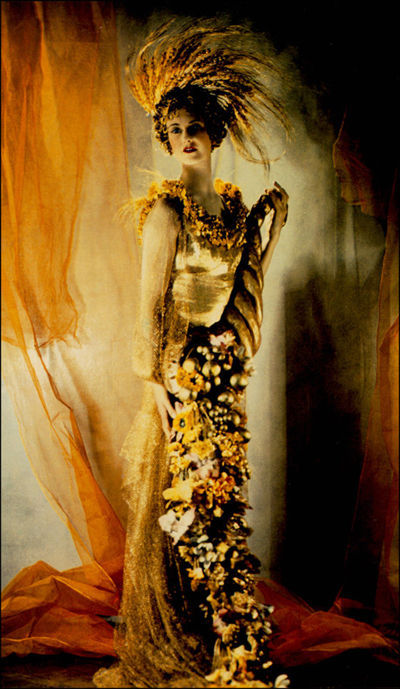

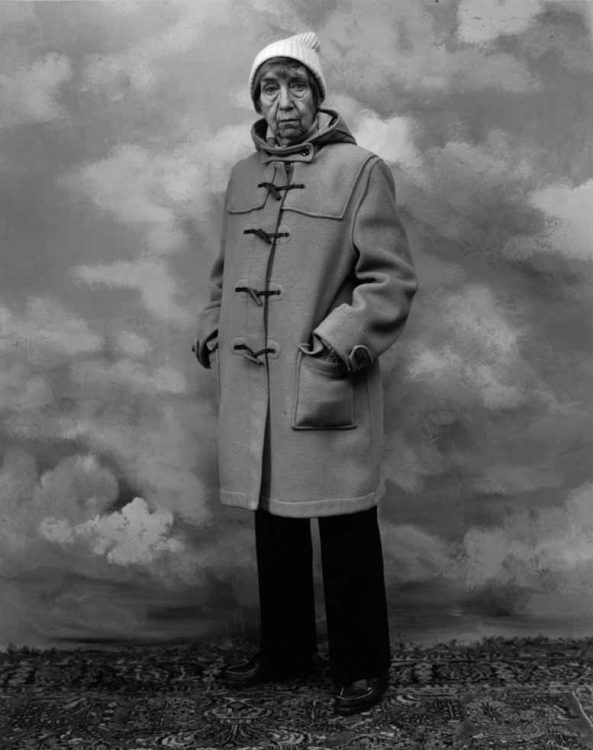

Madame Yevonde, one of the earliest feminists, was both an eccentric artist and a recognized professional photographer. He career got underway in 1910 when she became the assistant of Lallie Charles (1869-1919), a female photographer with a pictorialist bent. That same year, she joined the suffragette movement and campaigned for women’s voting rights. With her own studio, which she set up just before the First World War, she was keen to be different from traditional portrait agencies. In 1920, she married the playwright and journalist Edgar Middleton. In the 1930s, she received many advertising and commercial commissions, which she executed in an innovative way, especially through her use of colour, which made her famous. Convinced that photography was both a science and an art, she stepped up her technical research and, in the early 1930s, discovered the Vivex process, which she used up until the Second World War for many portraits which remained well-known, in particular her series of Goddesses, which she started in 1935. Each society portrait was interpreted in a mythological manner.

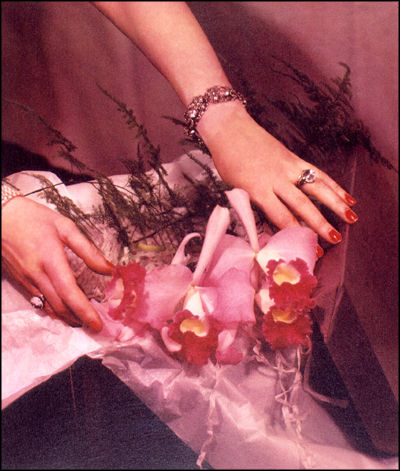

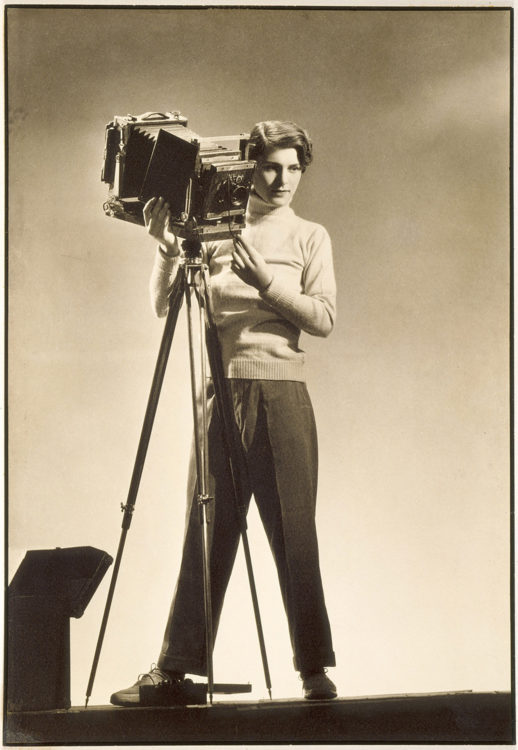

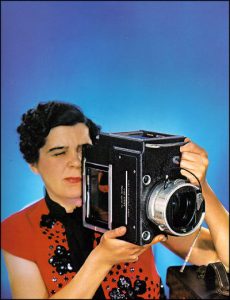

Lady Diana Mosley, wife of an English fascist leader, was Venus, while Mrs. Anthony Eden, wife of a labor politician, was the muse of History. In these almost surrealist parodies, the colours were gaudy, the features exaggerated, and the décors artificial. The series was formally daring, but also socially audacious for the irony with which the female depictions were questioned, from Medusa with her icy stare to Flora, romantic and innocent, by way of Minerva, symbol of militant androgyny. Like Claude Cahun and Cindy Sherman, the photographer played with female archetypes and the transgression of genders, especially in her self-portraits, like the one produced in 1940, where she puts herself under the auspices of Hecate. She wittily upturned erotic stereotypes when, for example, she exhibited Machine Worker in Summer (1937) at the Royal Photographic Society, a photograph of a naked woman in front of a sewing machine, in an allegorical décor. Her interest in the body also appeared in a series to do with tattoos (Tattoo Study, 1938). In her work, we also find that constant factor in female photography: the desire to come across as professional. So, in a 1937 self-portrait she posed elegantly holding a camera.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Lawrence Hole on Madame Yevonde, British Council

Lawrence Hole on Madame Yevonde, British Council