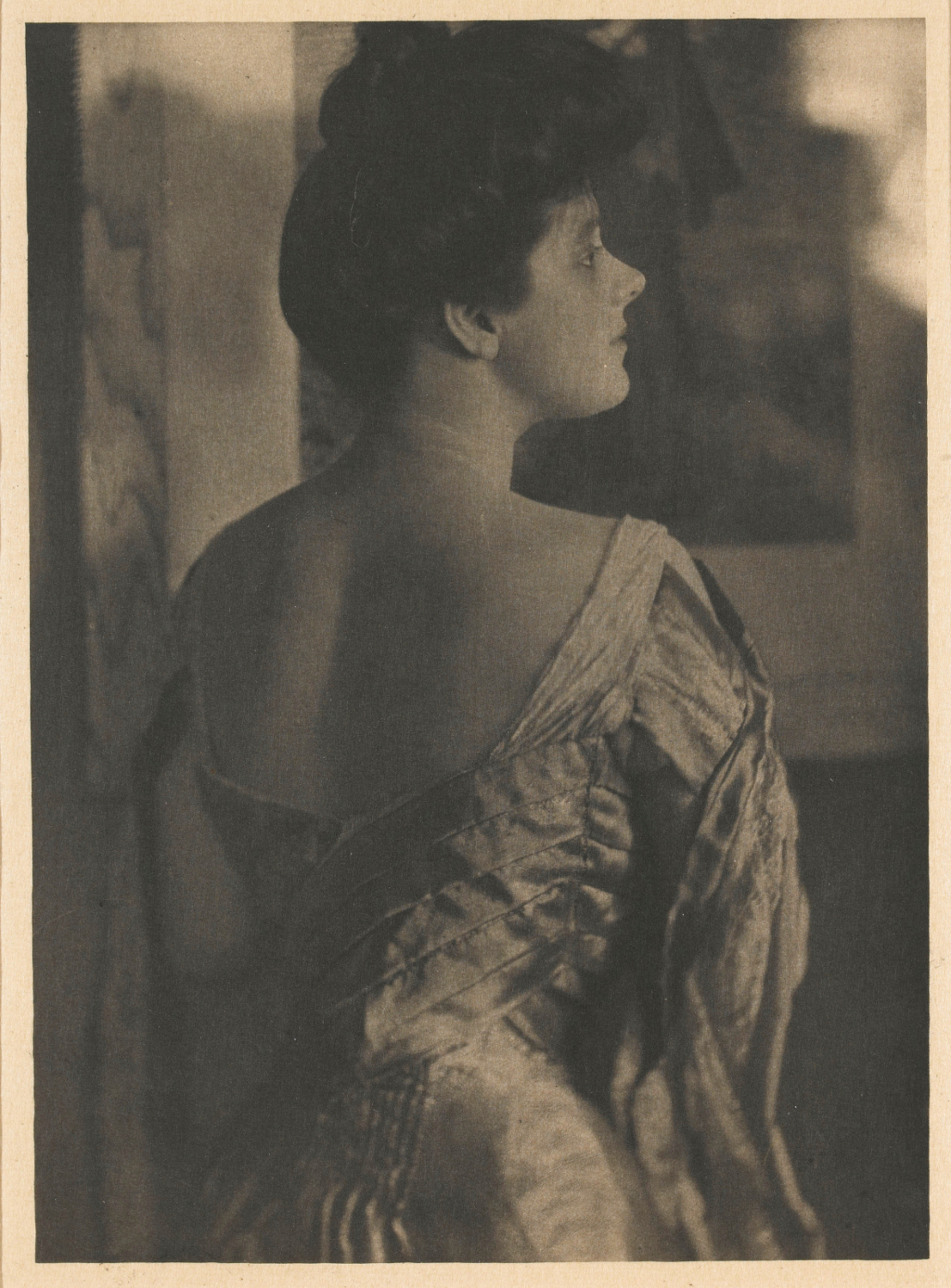

Gertrude Käsebier

Galifot Thomas, “Autour de Frances Benjamin Johnston, Gertrude Käsebier et Catharine Weed Barnes Ward: stratégies séparatistes dans l’exposition des femmes photographes américaines au tournant des XIXe et XXe siècles”, Artl@s Bulletin 8, no. 1, 2019

→Petersen Stephen and Tomlinson Janis A. (ed.), Gertrude Käsebier: The Complexity of Light and Shade, Newark, University of Delaware, 2013

→Michaels Barbara, Gertrude Käsebier: The Photographer and Her Photographs, New York, Harry N. Abrams, 1992

Gertrude Käsebier: The Complexity of Light and Shade, Delaware Art Museum, 2 March – 22 April 1979 ; Brooklyn Museum, May 12 – July 8, 1979

→A Pictorial Heritage : The Photographs of Gertrude Käsebier, Delaware Art Museum, 2 mars – 22 avril 1979, the Brooklyn Museum, February 6 – June 28 2013

American photographer.

Nothing predisposed Gertrude Stanton to becoming the urban and international artist she would go on to be at the turn of the 20th century. Born on the plains of the Midwest, she admitted that she suffered from growing up in an environment that did not value aesthetics. The Stanton family prospered thanks to her father’s sawmill in Colorado until the Civil War forced them to flee to Brooklyn, New York. G. Stanton received a solid education at the Moravian Seminary for Young Ladies in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, after which she returned to live with her family. She met one of the lodgers of her mother’s boarding house, Eduard Käsebier, an immigrant from a well-connected family in Germany, whom she married in 1874. His income as a shellac importer provided enough to support Gertrude in pursuing her first vocation as a portrait painter.

In 1889, at the age of thirty-seven and with her three children almost teenagers, she enrolled in the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where she studied painting for seven years in addition to practising photography on the side. By 1885 the latter medium had found its place in many homes but in the meantime, the passionate snapshot photographer that was G. Käsebier had developed further ambitions. In 1896 she had produced enough material to present her first solo exhibition at the Boston Camera Club, showing one hundred and fifty works.

Faced with her husband’s declining health and the need to secure her family’s future finances, she decided to pursue photography as a profession. At the turn of 1897 and 1898 she opened her first New York commercial portrait studio. Its immediate success allowed her to transfer the premises to Fifth Avenue in 1899.

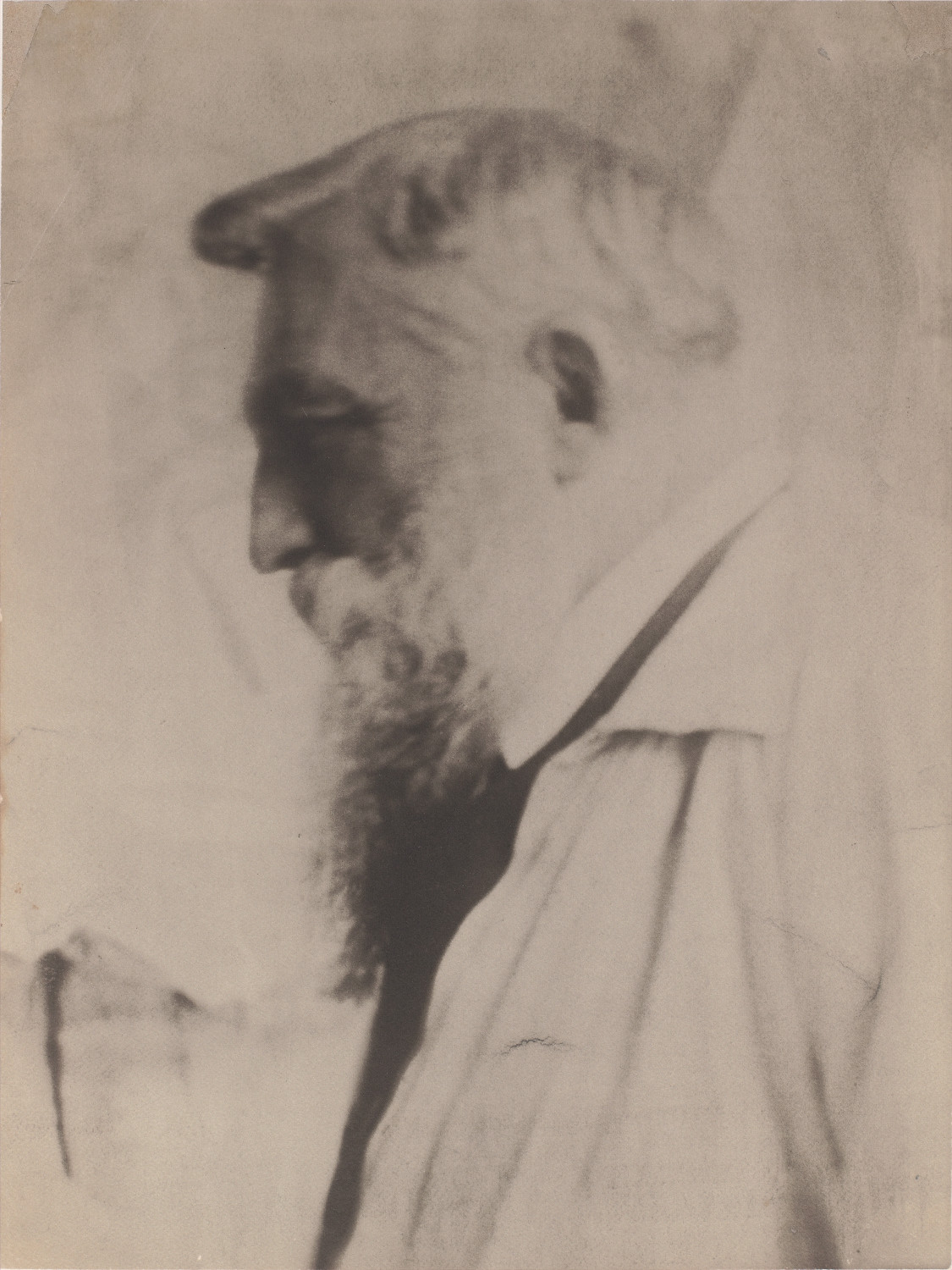

G. Käsebier did not abandon, however, her ambition to make a name for herself as an artistic photographer – a recognition that was earned when she took part in the Philadelphia Salons in 1898 and 1899. In 1900 she became the first woman to become a member of the Linked Ring Brotherhood in London (with Carine Cadby, British). A year earlier she had entered the sphere of influence of Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946). The critic and photographer gave Käsebier, whom he praised as “beyond dispute the leading portrait photographer in this country”, pride of place at the New York’s Camera Club and in the columns of his journal Camera Notes.

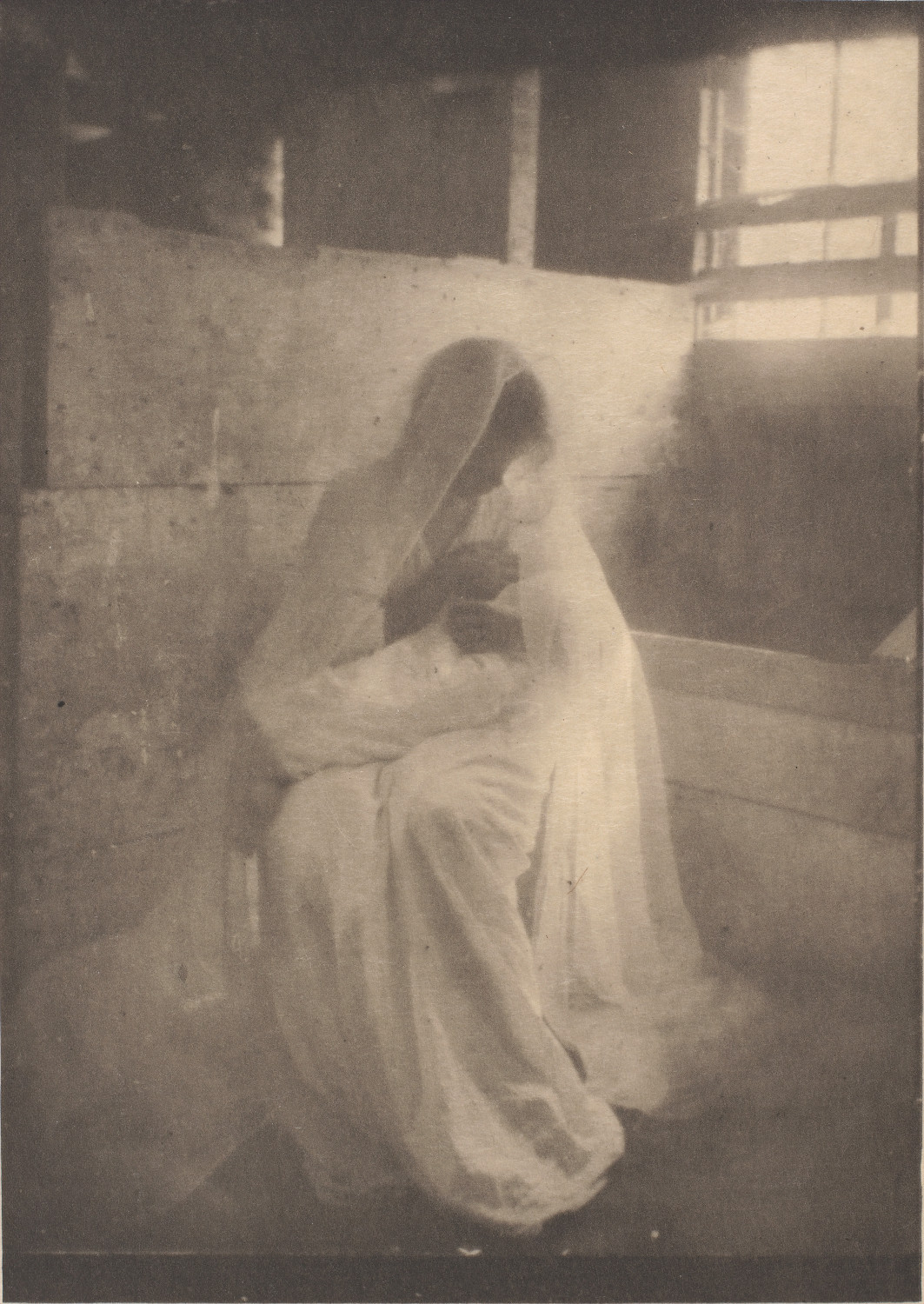

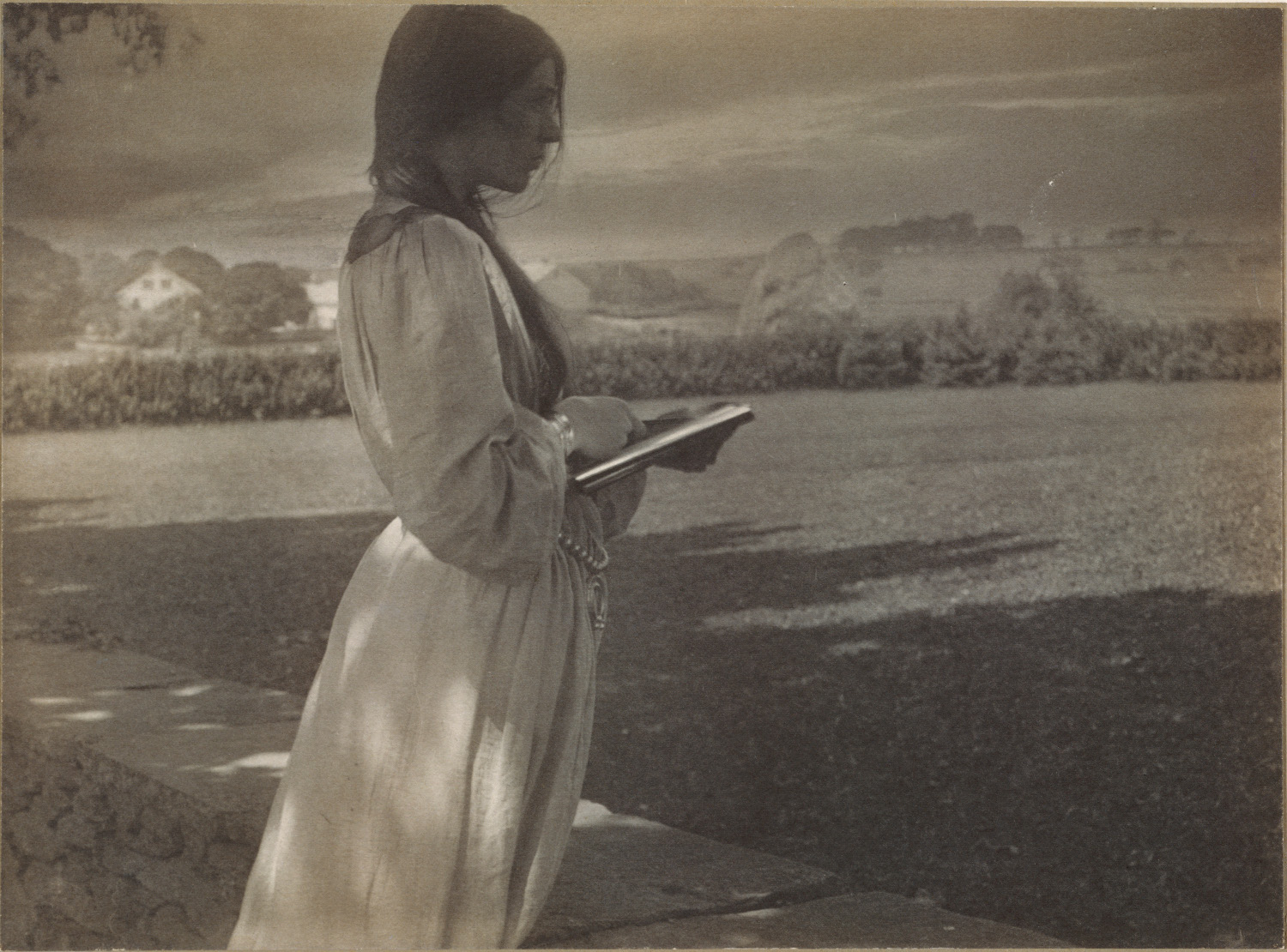

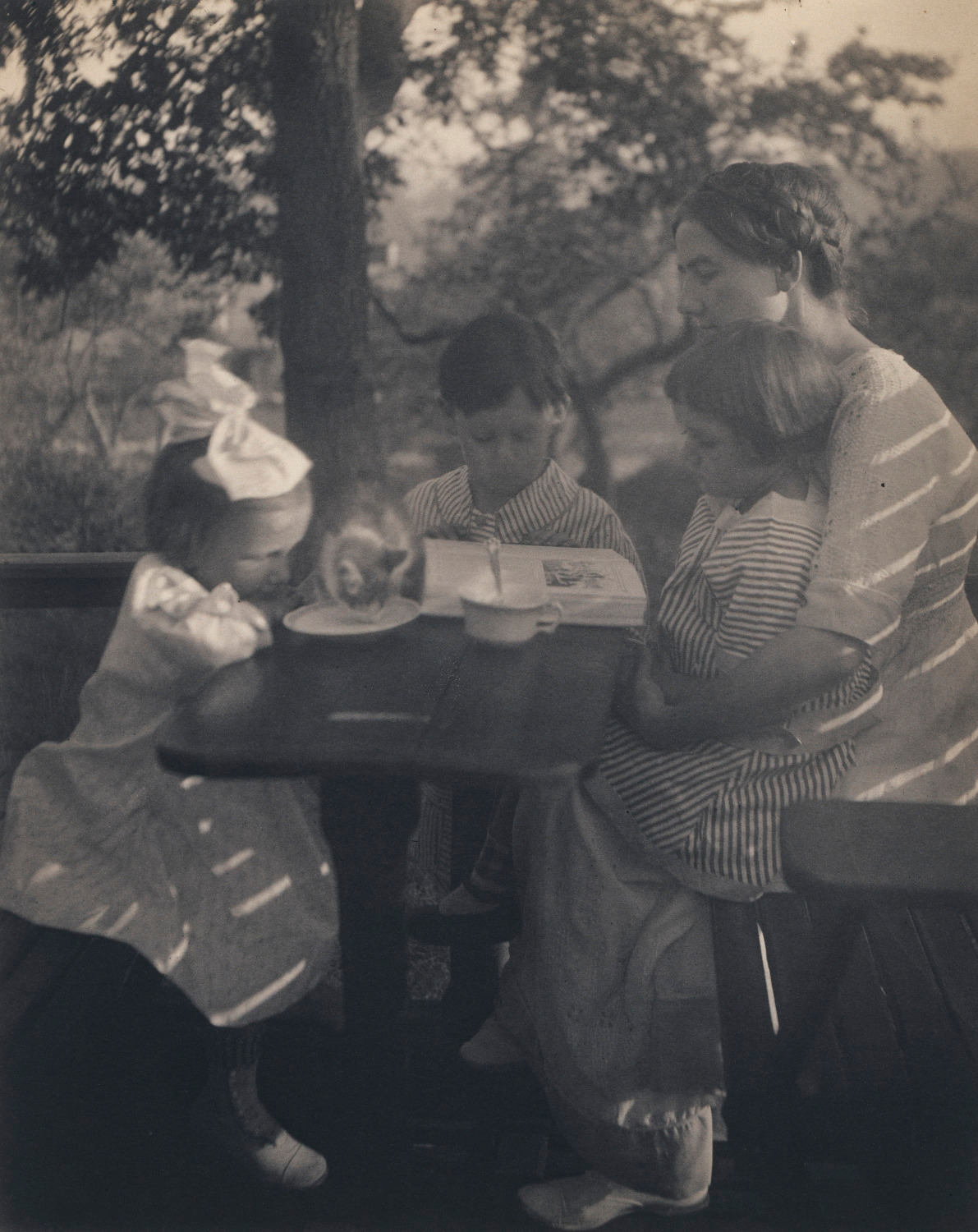

The following sequence confirmed her rapid rise to fame and is the best-known period in the artist’s life and work. Her portraits and scenes around themes of motherhood and childhood, achieved using sophisticated processes such as gum bichromate and platinum printing, fed into the aesthetic canons of the Photo-Secession. In 1902, G. Käsebier co-founded this group initiated by A. Stieglitz, who would make it the most elitist American branch of international Pictorialism – the first artistic movement in the history of photography.

The most recently highlighted aspect of G. Käsebier’s career is the way she used her reputation to advocate for the collective cause of women photographers. One of the major aspects of such a commitment was her strong involvement, around 1909, in an unprecedented association of professional women photographers, the Women’s Federation of the Photographers’ Association of America, whose exhibition policy she launched and legitimized. It was this attachment to her professional status that led Käsebier to fall into disfavour with the aesthete Stieglitz. In 1912 she was the first member to resign from the Photo-Secession, soon followed by Clarence H. White (1871-1925), with whom she founded the Pictorial Photographers of America four years later. After having been honored by a few solo exhibitions in North American museums from 1929, G. Käsebier, whose works were very successful at the Parisian photography Salons of the early 20th century, was eventually rediscovered by the French public on the occasion of the exhibition Qui a peur des femmes photographes? 1839-1919 at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris in 2015.

Publication made in partnership with musée d’Orsay.

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions