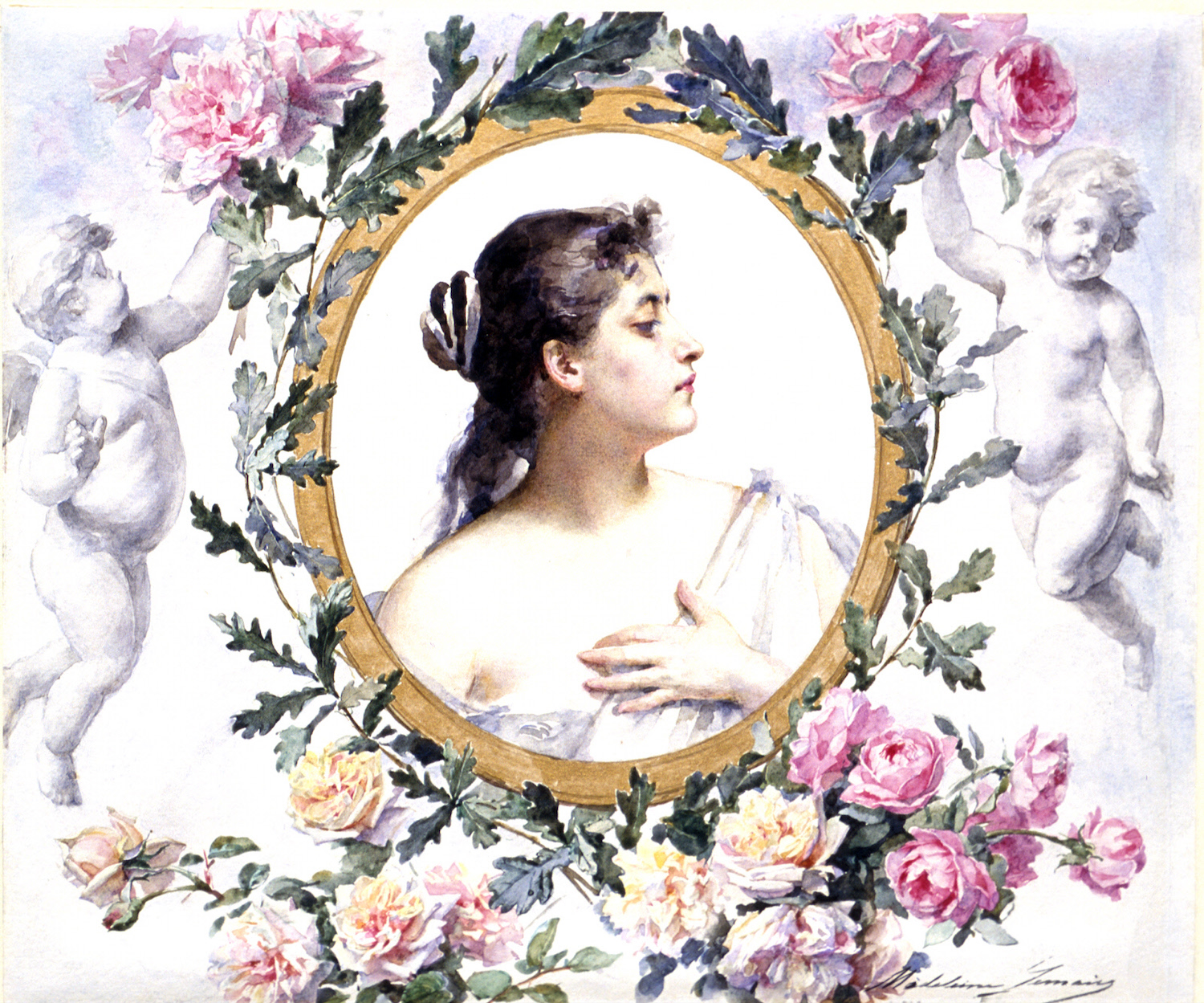

Madeleine Lemaire (Jeanne Magdelaine Lemaire, dite)

Ripa Yannick, “Madeleine Lemaire, l’impératrice des fleurs”, in Ripa, Yannick (ed.), Femmes d’exception. Les raisons de l’oubli, Le Cavalier Bleu, coll. Mobilisations, 2018, p. 159-166.

→Uro Yves, Madeleine Lemaire, une amie de Marcel Proust, Paris, l’Harmattan, 2015

→Petit Georges, Catalogue des aquarelles, dessins, gouaches et sanguines par Madeleine Lemaire, Paris, c. 1897

Femmes peintres et salons au temps de Proust : de Madeleine Lemaire à Berthe Morisot, Musée Marmottant Monet, Paris, April – June 2010

→Madeleine Lemaire, Galerie Charpentier, Paris, 1923

French painter, pastellist and illustrator.

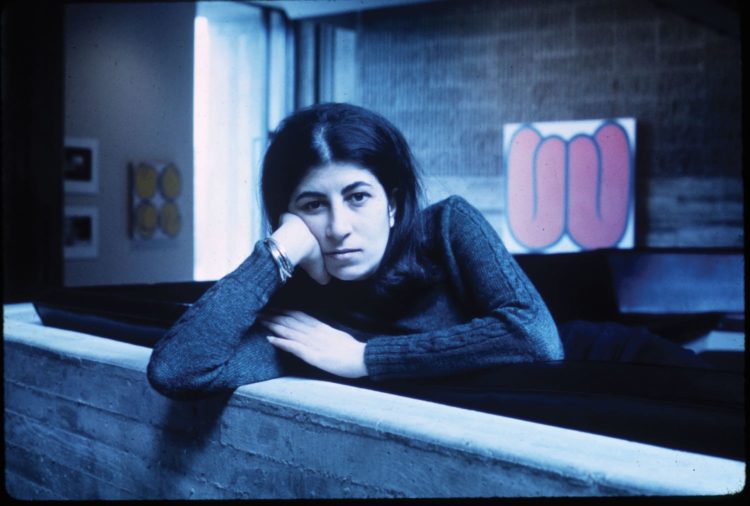

Recognised for her natural authority, energy and humility, Madeleine Lemaire is perhaps better known to us as the socialite Madame de Villeparisis and the tyrannical Madame Verdurin in Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. A few photographic portraits show her in her studio, a conservatory in the Plaine Monceau district where she entertained guests from all walks of life. Every Tuesday evening, writers, musicians and actors from the Comédie-Française and politicians flocked to her very sought-after musical and literary salon. The dandy Robert de Montesquiou was a regular visitor. Tenor Reynaldo Hahn won over his first audiences there, and M. Proust was initiated into the fever of socialite life at her salon in 1891. In the summer, the whole company was hosted by their benevolent friend at her Château de Réveillon in the Marne, where M. Proust wrote Les Plaisirs et les Jours while R. Hahn created four piano pieces and M. Lemaire painted watercolours of wildflowers.

Born into the upper middle-class, the daughter of General Baron Joseph Habert and niece of famous miniaturist Mathilde Herbelin (1820-1904), who also ran a salon, M. Lemaire developed social skills that benefitted the practice of her art. However, she refused to remain confined to the salons. Villeparisis and Verdurin only briefly outshine the independent artist she was, who was resolved to assert herself amidst a very masculine assembly. M. Lemaire had spent her childhood in the presence of artists. Her aunt was her first teacher, and Charles Chaplin (1825-1891) later became her tutor. The portraits she exhibited at the Salon from the age of nineteen showed the influence of 18th-century art. Her marriage to municipal civil servant Camille Lemaire in 1870 and subsequent motherhood never prevented her from working tirelessly to perfect her precocious talent. Her relationship with Alexandre Dumas fils cemented her position within the artistic elites and marked her emancipation and her move towards a more personal output.

As an illustrator, watercolourist and pastellist, M. Lemaire was a draughtswoman. She was a founding member of the Société des Aquarellistes Français (Society of French watercolourists) in 1879 and of the Société des Pastellistes Français (Society of French pastellists) in 1885, and advanced her ambitions alongside men, as equals. Pastel work was open to women and they entered into competition with male pastellists unlike women-only fields as watercolours or miniatures. Building a career in the field was harsh: only M. Lemaire and Marie Cazin (1844-1924) were allowed into the society. In 1893 she and Louise Abbéma (1853-1927) were the first two female members of the Salon’s jury. M. Lemaire also took part in World’s fairs. In 1893 she was part of the French delegation at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. She designed the official poster and wrote the catalogue for the Woman’s Building exhibition. In 1898 she exhibited at the Venice Biennale. She was also appointed as a “drawing teacher” at the French National Museum of Natural History in 1899.

J. M. Lemaire received an honourable mention at the 1877 Salon and a silver medal for her entire body of work at the 1900 World’s Fair. In 1906 the readers of Femina magazine elected her vice-president of the Femina Prize. She was made Knight of the Legion of Honour in 1908. The ultimate acknowledgement of having one of her works bought by the state never came. However, the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Troyes acquired a sanguine portrait of a woman in 1918 thanks to the Millard legacy. As host of a salon, M. Lemaire was nicknamed “patronne” (boss), and as a painter she was dubbed “impératrice (des roses)” (empress of the roses) by R. de Montesquiou; above all, she fulfilled her destiny as a determined, uncompromising woman.

Publication made in partnership with musée d’Orsay.

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2021