Marcelle Renée Lancelot-Croce

« Un’artista nel Senato del Regno: Renata Lancelot Croce » [An artist in the Senate of the Kingdom: Renata Lancelot Croce], MemoriaWeb – Trimestrale dell’Archivio storico del Senato della Repubblica, n° 29 (nv série), March 2020

→Schaal Katia, « La médaille de sculpteur, essor d’un genre à l’époque de la ‘médaillomanie’ (1880-1920) », PhD thesis under the direction of Claire Barbillon and Inès Villela-Petit, Poitiers-Paris, University of Poitiers/École du Louvre [in progress]

→Ferlier Ophélie, « Marcelle Renée Lancelot-Croce », in Chevillot Catherine, Papet Edouard (ed.), Au creux de la main. La médaille en France aux XIXe & XXe siècles, Paris, Skira-Flammarion, Musée d’Orsay, 2012, p. 93.

French sculptor and medallist, Italian by marriage.

Marcelle Renée Lancelot was born to a family of artists. She was the daughter of lithographer Dieudonné Lancelot (1822-1894) and older sister of sculptors Camille Lancelot (1864-1892) and Gabriel Lancelot (dates unknown). In addition to her father’s tuition, she studied in the studios of Hubert Ponscarme (1827-1903) and Eugène Delaplanche (1831-1891). Endowed with precocious talent and the dual ability to model bas-reliefs and carve steel medals, she exhibited as from 1878 at the Salon des Artistes Français, in both the sculpture and medal engraving sections. In 1888 her portraits earned her an honourable mention. The following year she received another honourable mention at the World’s Fair and a third-class medal and travel grant for her presentation of Le Champagne (1889) at the Salon – a first for a woman. She spent the year 1890 travelling around Italy and stayed in Rome. It was on this occasion that she met sculptor Leonardo Croce (1852-1934), whom she married in 1892.

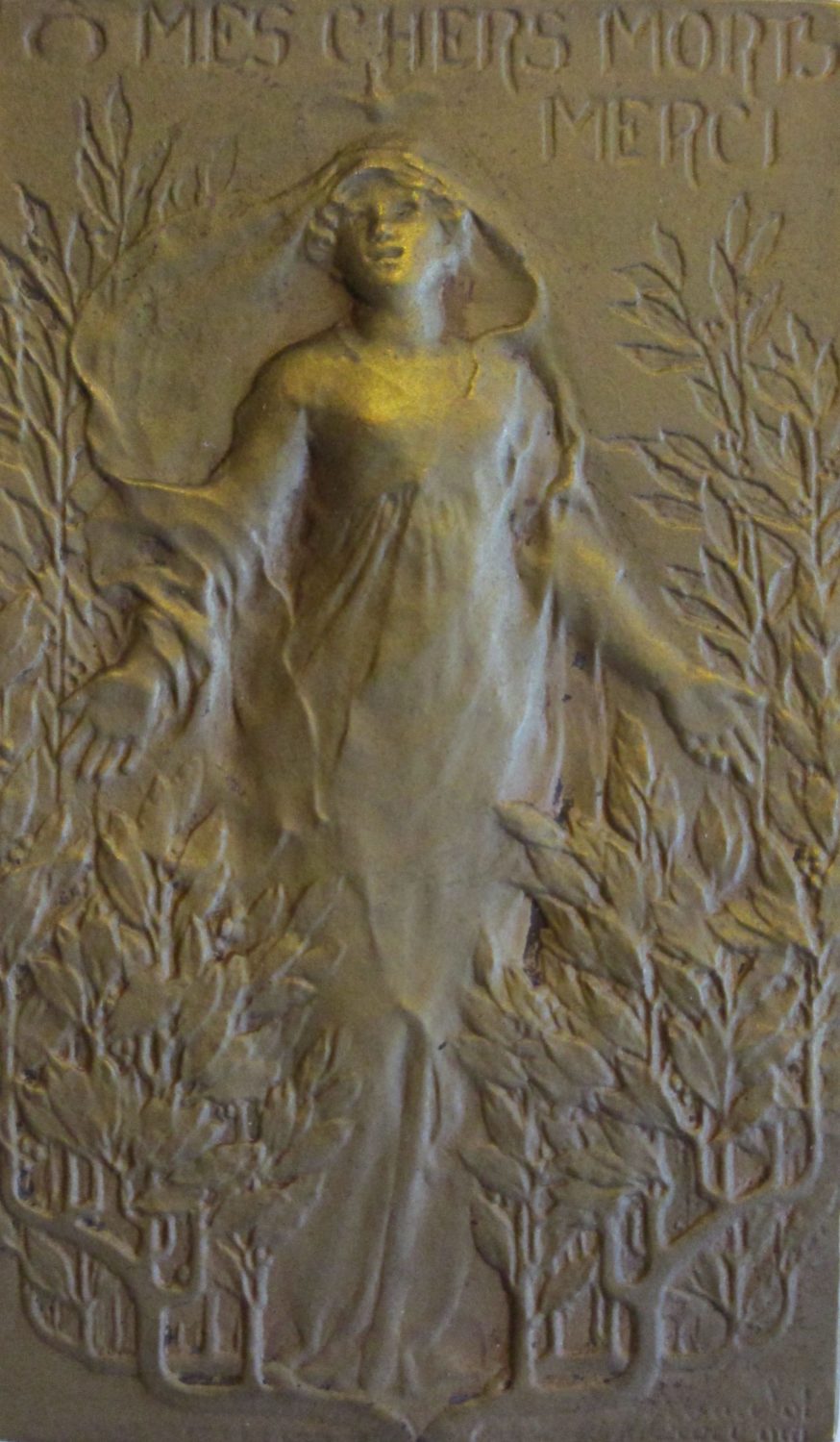

She settled in Italy and became a member of the Accademia di San Luca (corresponding member in 1897, deputy in 1905, and emerita in 1946) and the International Circle in Rome, and began producing medals for the Italian authorities (Pope Leo XIII, 1900; Umberto I, 1901; Émile Loubet on a Visit to Rome, 1904). However, she never ceased to send pieces to the Salon des Artistes Français in Paris. Her work was always welcomed there with interest, and she won a second-class medal in 1894 with La Femme et ses destinées (Woman and her destinies, 1894), as well as the grand prize at the Fine Arts Exhibition in Rome that same year. She reached the peak of her career at the 1900 World’s Fair, where the jury awarded her a gold medal and the French government made her Knight of the Legion of Honour. In 1906 the jury of the Milan World’s Fair awarded her another first prize.

Critics praised the fluidity of her style, her ability to model reliefs without artificially accentuating them, and the ease with which she faithfully depicted her contemporaries and the inventiveness of her symbolic motifs. These qualities tied her to the neo-Baroque aesthetic that was fashionable in sculpture at the time and which contributed to the renaissance of French medal crafting in the years 1890 to 1910. However her Italian marriage led Parisian critics, particularly Charles Saunier, to contest her status as a French sculptor-medallist and to categorise her in the Italian school. In Rome her application for the title of chief engraver of the Italian Mint was rejected at the first evaluation stage in 1913 on the grounds that she was a woman, despite her undeniable talent.

Because medals were a form of reproducible art, copies of her works can often be found in various French museums, including Rouen, Lille and Narbonne. The Musée d’Orsay holds a set of twenty-four medals, plaques and plates, half of which were acquired in 1914. In addition to the collections of the Monnaie de Paris and legal deposits kept at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the largest collection of her works is kept at the Musée des Beaux-arts in Troyes. The artist’s family ties enabled her to spend time in the Aube region periodically and to find refuge there during World War I. The painter and curator of the Musée de Troyes, Dieudonné Royer (1835-1920), who was also her godfather, was instrumental in some of these acquisitions, while the rest came from a donation the artist made to the Société Académique de l’Aube in 1938. The set of works comprises fourteen drawings, three portraits on canvas, three sculptures and forty-four medals, which have yet to be studied, as they are unfortunately kept in storage.

Publication made in partnership with musée d’Orsay.

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2021