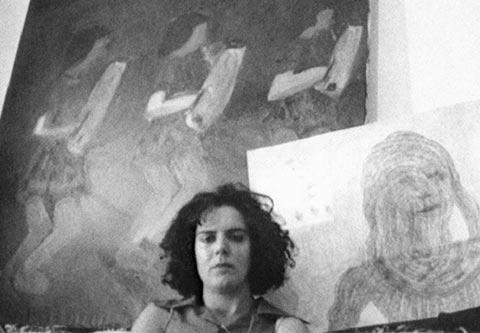

Marianne von Werefkin

Werefkin Marianne, Lettres à un inconnu, Paris, Klincksieck, 1999

→Brogmann Nicole (ed.), Marianne von Werefkin: Œuvres peintes (1907-1936), exh. cat., Fondation Neumann, Gingins (9 May–25 August 1996), Gingins, Fondation Neumann, 1996

→Malycheva Tanja, Wünsche Isabel, Marianne Werefkin and the Women in Her Circle, Bremen, Jacobs University, 2016

Marianne von Werefkin: Œuvres peintes (1907-1936), Fondation Neumann, Gingins, 9 May–25 August 1996

→First Exhibition by the Editors of the Blue Rider, Moderne Galerie Tannhäuser, Munich, December 1911–January 1912

→Storm Women. Women Artists of the Avant-Garde in Berlin 1910–1932, Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt am Main, 30 October 2015–7 February 2016

Russian painter.

Daughter of a general-in-chief, Marianne von Werefkin had an aristocratic upbringing and her mother, a painter, encouraged her to develop her artistic abilities. For ten years, from 1886 on, she was a student of Ilya Repin, the greatest realist painter of the day, in Russia. In 1888, her right hand was seriously injured, but she nevertheless invented a system enabling her to hold a brush and carry on painting. Nicknamed the Russian Rembrandt, she deliberately moved away from Romanticism and Realism, and tried to achieve her own artistic goals. Among the works of that period—most of them now vanished—was an 1893 self-portrait (Self-Portrait in a Sailor’s Blouse). Through her mentor, she met Alexej von Jawlensky, with whom she immediately had a very strong relationship—he would be her life companion until 1921. In 1896, they went to Munich, then an artistic capital and a source of the pictorial revival she was heading towards.

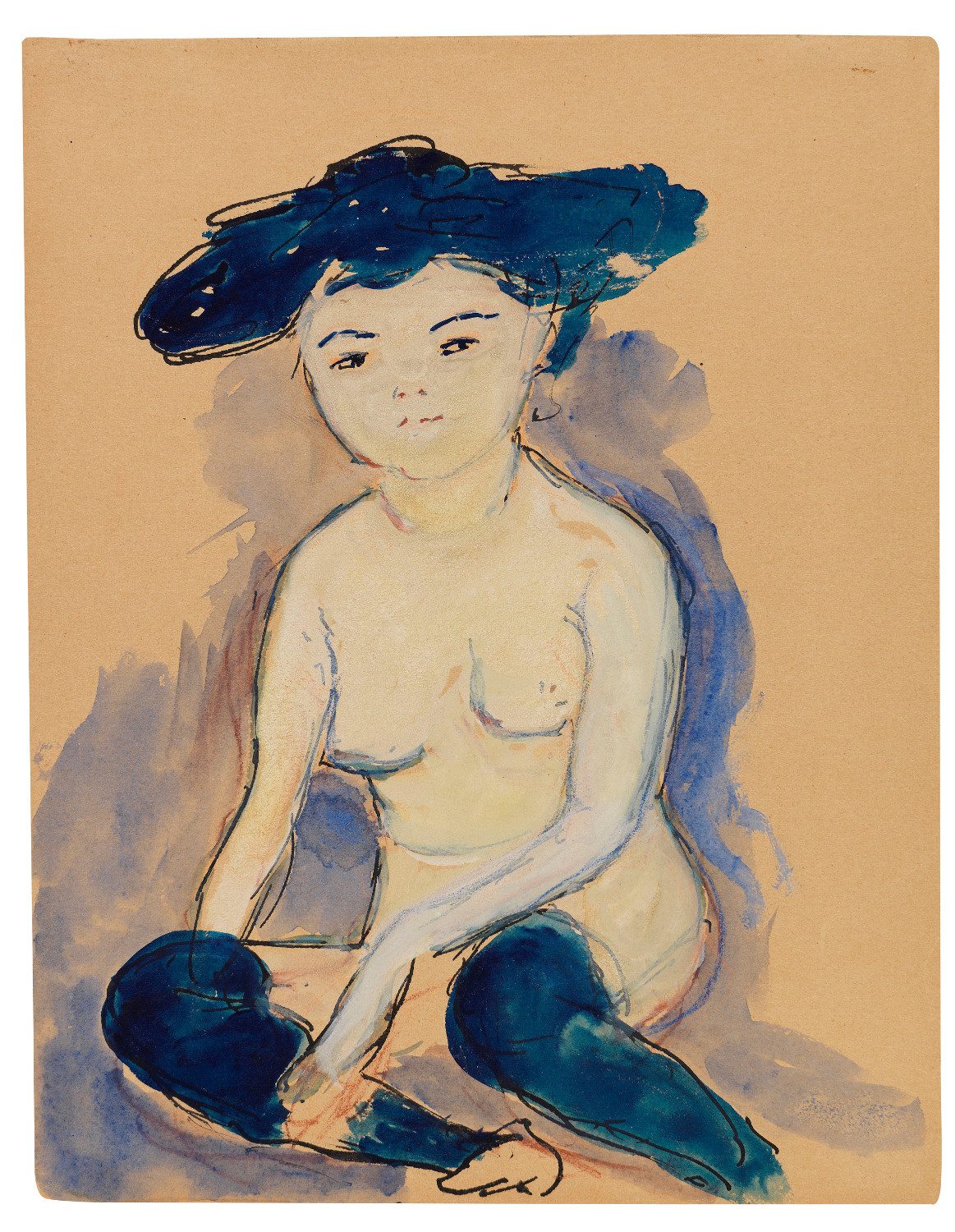

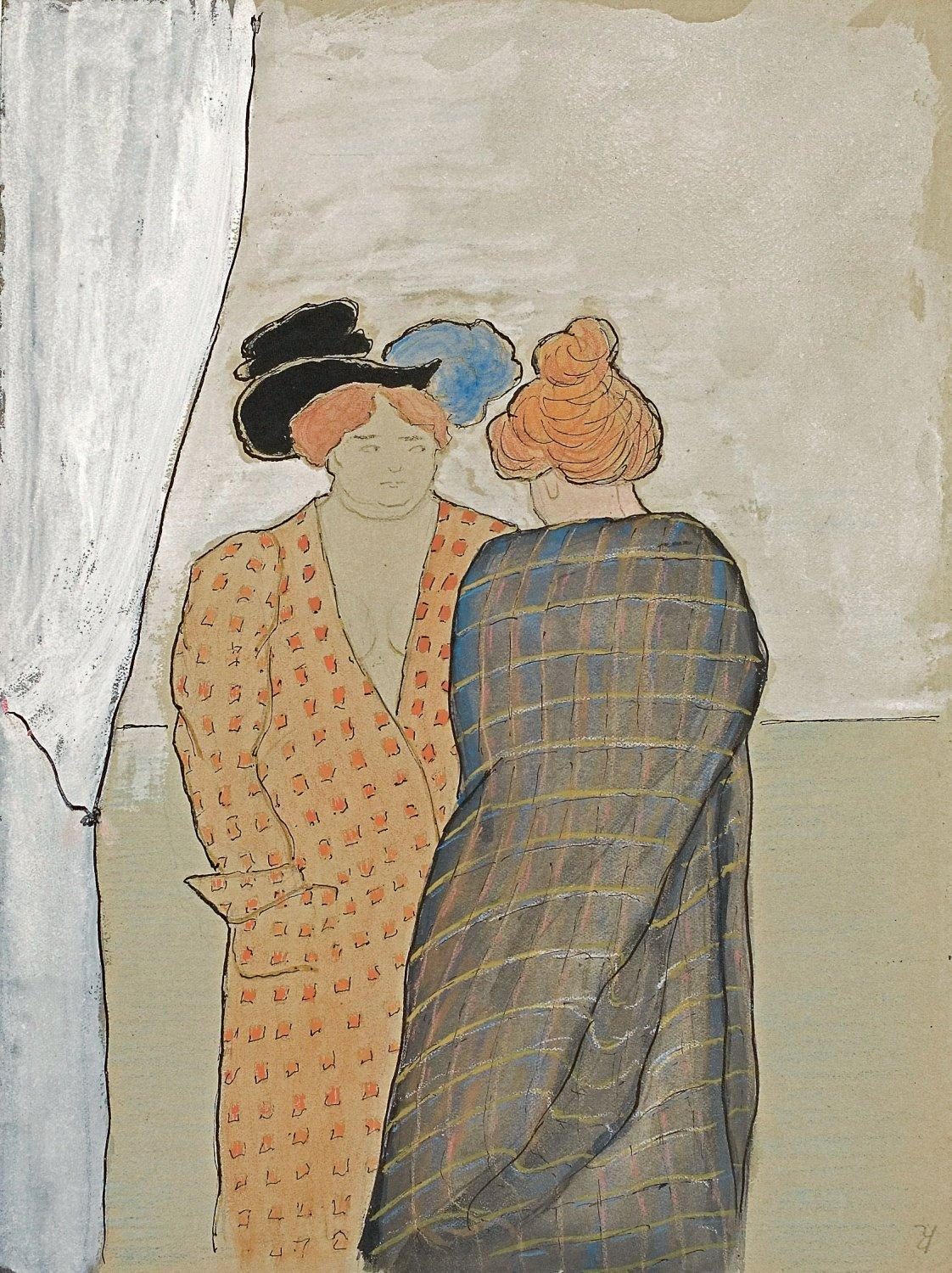

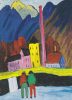

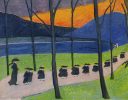

Her home became a salon governed by a way of thinking stimulated by her dazzling personality and conducted by the confraternity of St. Luke, founded in 1809 by young painters at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, brought together by bonds of friendship and one and the same line of visual research. Vassily Kandinsky, Gabriele Münter and then Paul Klee all lived in the vicinity. The subjects broached were mentioned in the diary she kept between 1901 and 1905, Lettres à un inconnu [Letters to a Stranger] (1999), in which she jotted down the ways of thinking which would lay the foundations for Munich Expressionism; those notebooks attest to her indefatigable personal quest and convey her observations about art, in a period when she had stopped painting. Marianne von Werefkin in fact devoted herself assiduously to the development of Jawlensky’s career, while going through a deep-seated crisis of moral and artistic identity. Since they first met, she supported him in the hope that he would realize, in tangible form, the new art to which she aspired. Impaled on a traditional conception of genius, and subject to the gendered norms of the artistic arena, she reckoned that only a man could incarnate a real stylistic revolution, deeming herself too weak to do so as a woman. That state of mind lay at the root of fearsome quarrels between them, further poisoned by the affair that Jawlensky was having with one of their maids, with whom he would have a child. Humiliated, Marianne von Werefkin gave up painting for a while; she nevertheless pursued her thoughts about a new art form: “emotional art”. A stranger to the world of Realism and Symbolism, she expressed the need for a painting that would explore new stylistic avenues, based on the “sincerity” of the emotions conveyed by the painter. In 1903 and in 1905, she travelled to France, where she discovered the painting of Henri Matisse and the Nabis, which, in its use of colours and drawing using flat tints, tallied with her idea of a new art. Disappointed by Jawlensky’s work, she started painting again in 1906, choosing gouache and tempera, and discovered a new dynamic and luminous strength in colour. She opted for a fluid kind of drawing which is radiant in her notebooks, illustrated by more than 400 sketches. Dance, to which she attributed great expressive power, was an essential subject in them—the painter was in fact a friend of Diaghilev (1872-1929) and was very well acquainted with the work of Alexandre (1886-1963) and Clothilde Sakharoff (1892-1974). Like Kandinsky in the same period, she theorized about the importance of a liaison between the arts: music, dance and painting. The painter’s notion of “inner need” linked up with her idea of “sincerity”: according to her, painting should faithfully convey the resonance and rhythm of the image, the visible and the invisible forming it, and its relation with colours. In 1909, in her salon, the new association of Munich artists was founded, bringing together, among others, Kandinsky, Jawlensky, Münter, Adolf Arbslöh, and Alfred Kubin. When the First World War broke out, Marianne von Werefkin emigrated to Switzerland. In 1918 she set up home in Ascona where, in 1924, she created the art group Grosser Bär, and carried on her work until her death, in 1938. Among the main subjects of her works, many of which are held in Ascona, we find women, often portrayed at work and in their daily lives, passers-by and the theme of the path: landscapes, in particular the Swiss mountains where she lived, are also present, accompanied by human figures which symbolize the eye cast by the painter upon the world.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017