Marie Bashkirtseff

Tatiana Shvets, L’Élue du Destin Marie Bashkirtseff, Moscow, Osobaja kniga, 2018

→Dominique Rochay, Jean Forneris, Jean-Paul Potron (eds.), Marie Bashkirtseff : peintre et sculpteur, écrivain et témoin de son temps, Nice, Régie autonome des musées de la Ville de Nice, 1995

→Cosnier Colette,, Paris, Pierre Horay, 1985

Marie Bashkirtseff : peintre et sculpteur, écrivain et témoin de son temps, musée des Beaux-Arts, Nice, July 1 – October 29, 1995

→Marie Bashkirtseff, musée Russe, Saint-Pétersbourg, 1929

→Rétrospective en hommage à Marie Bashkirteseff, Exposition de l’Union des femmes peintres et sculpteurs, Paris, 1885

Russian painter, draughtswoman and pastellist.

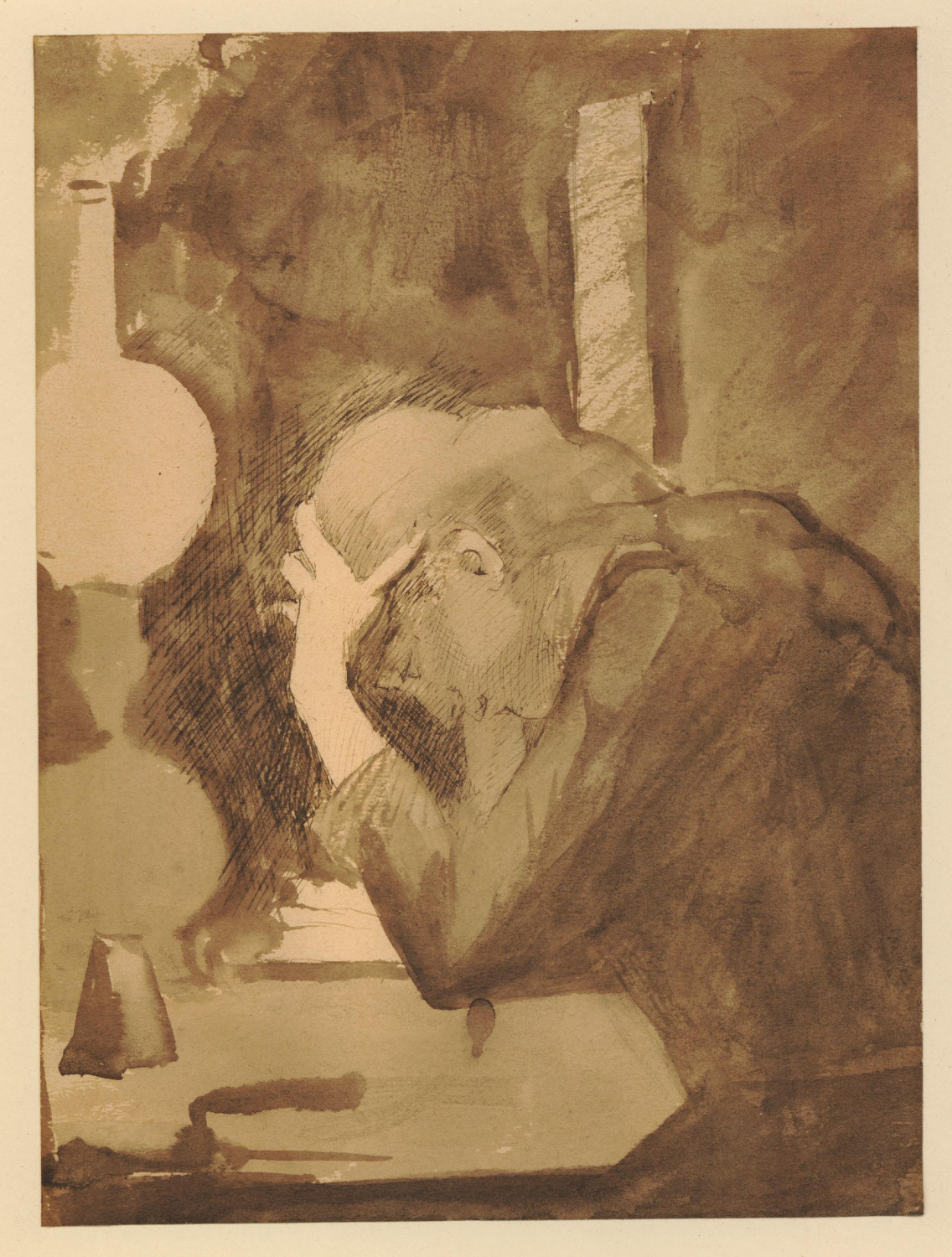

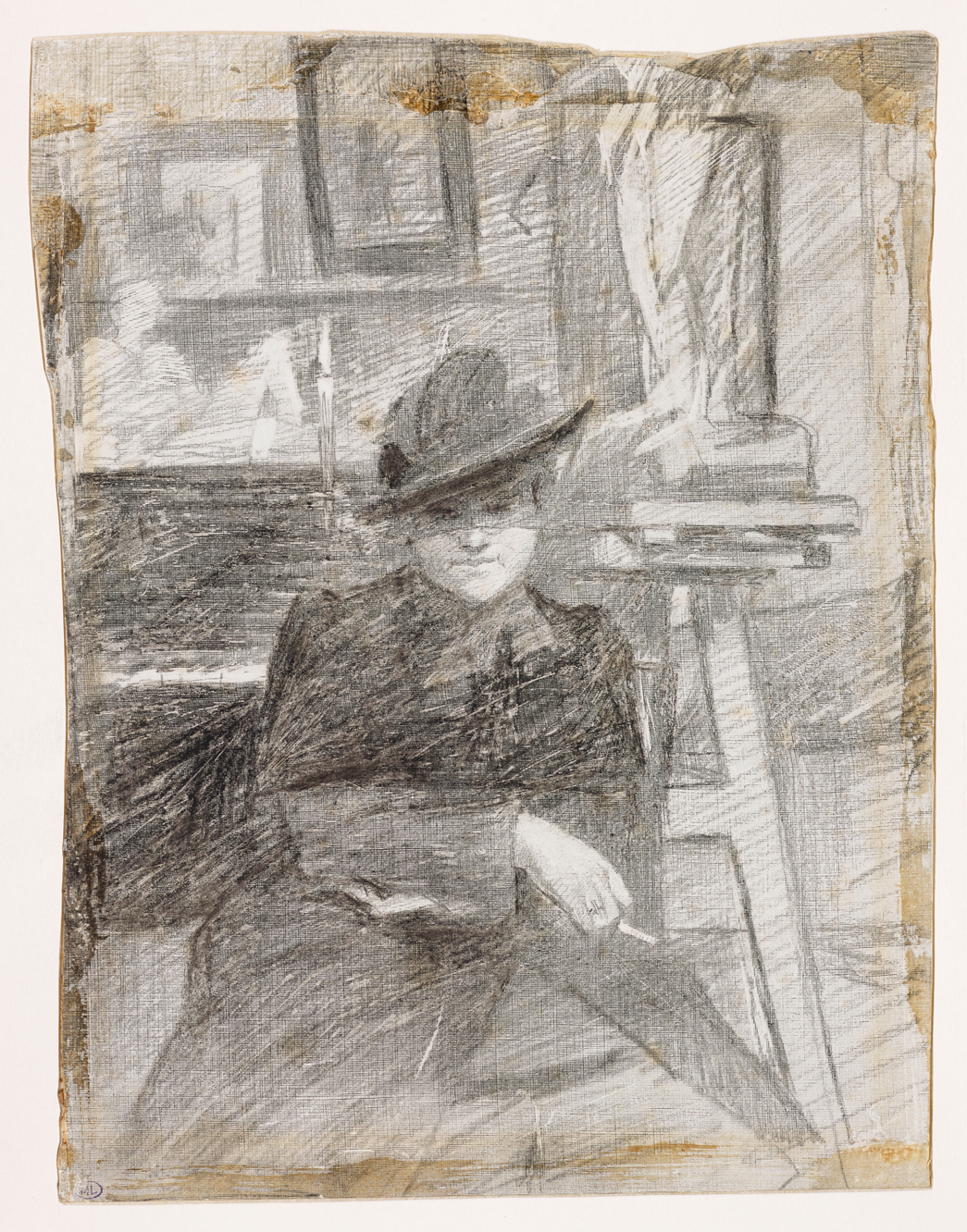

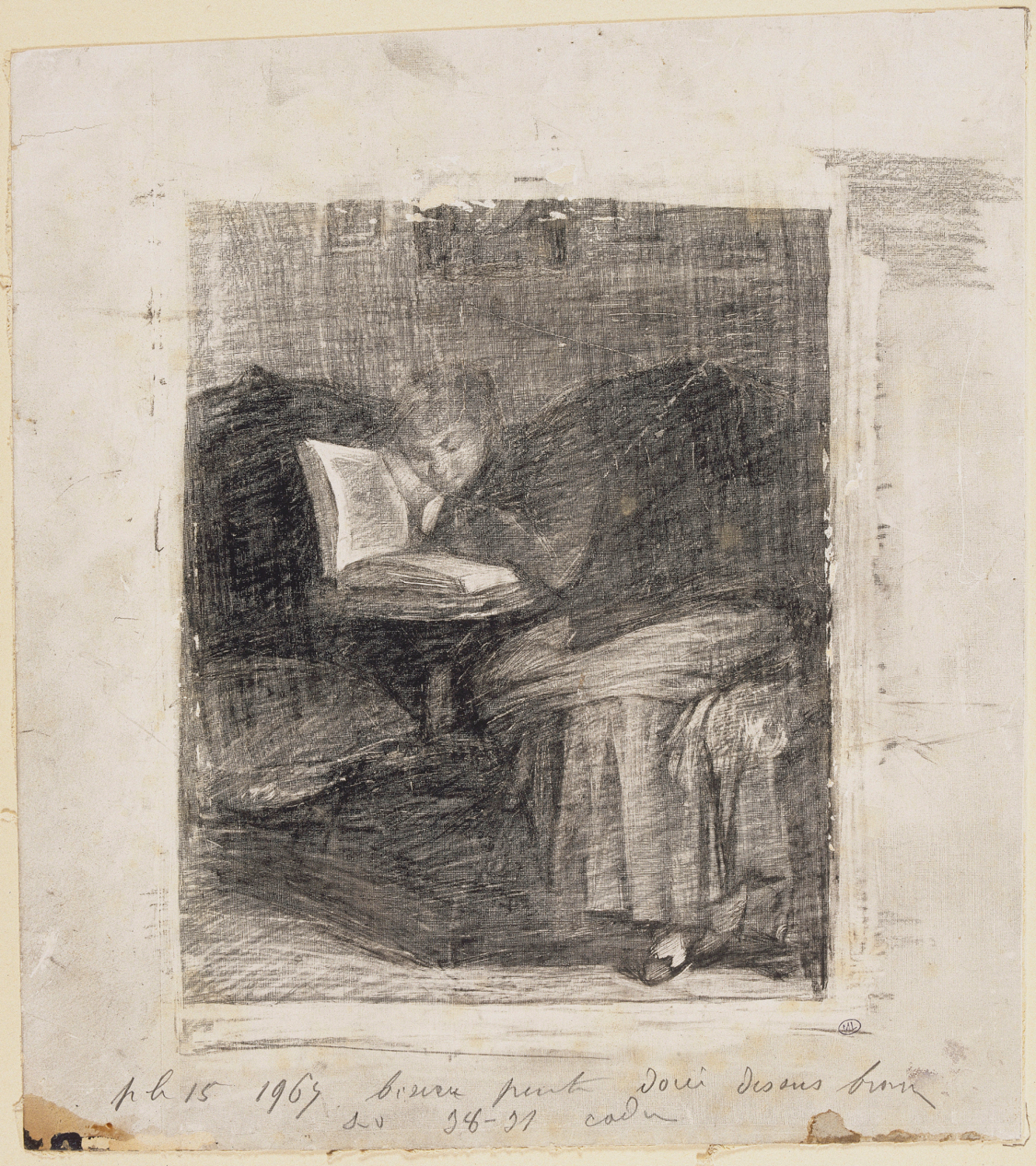

Born into a Russian aristocratic family, Marie Bashkirtseff received a refined education from a young age, alternating between dance, music and drawing lessons. Her artistic career mainly took place in France, far from her home country, which she left when she was twelve. From then on, she would lead a cosmopolitan life throughout Europe before finally settling in Nice in 1870. There, she received drawing lessons from François Bensa (1811-1895) and Charles Nègre (1820-1880) and discovered a passion for painting while taking lessons with Wilhelm Kotarbiński (1848-1921) in Rome. M. Bashkirtseff had dreamed of becoming an opera singer, but because tuberculosis altered her mezzo-soprano voice, she chose to become a painter instead and enrolled in the Académie Julian in Paris in 1877 as a student of Tony Robert-Fleury (1837-1911). Her painting L’Académie Julian (1881) offers a rare account of life at the women-only atelier, where male nudes without loincloths were still forbidden at the time.

The 1880s were a major step in M. Bashkirtseff’s artistic career. In 1881, after becoming aware that she would not be able to take part in the academy’s cursus honorum because of her gender, she contributed to the feminist newspaper La Citoyenne under the alias Pauline Orrel to demand access to fine arts schools for women. This decisive period coincided with a break from academic standards, which she materialised during a stay in Spain when she made a copy of Apollo in the Forge of Vulcan by Diego Velázquez (1599-1660) at the Prado Museum and developed a “Hispanicised” style in her paintings of a prison convict and of the picturesque streets of Granada. Upon returning to France, her fascination for the ideas of Émile Zola and her acquaintance with Jules Bastien-Lepage (1848-1884) led her to take part in the naturalist movement, the aesthetics of which espoused her humanist and social views. The popular figures of the Parisian faubourgs became her preferred iconographic repertoire. The gamins on the streets of Paris became subjects of research and recurring models in her work, as in Un meeting (1884), which earned her accolades at the 1884 Salon.

In her search for her own artistic style, M. Bashkirtseff also became interested in avant-garde innovations. She asserted close ties with the art of Édouard Manet (1832-1883) and put into practice the contributions of the Impressionists by exploring the possibilities of outdoor painting. However, her intentions differed from Impressionist orthodoxy: in Le Printemps [Spring, 1884], she attempted to create a symbiosis between a young labourer and the surrounding nature by using the same colour range (browns and greens) and near-photographic approach to outdoor scenes as Jules Bastien-Lepage. At the same time, fearing that she had little time left to live, she explored subjects close to her heart and influenced by Symbolism, like pain and solitude. She turned her sights to literary and biblical female figures, as seen in her sculpture Douleur de Nausicaa [Nausicaa’s Pain, 1884], inspired by Homer’s Odyssey, and her last painting, Les Saintes Femmes [Holy Women, 1884], which shows uncommon ambition. M. Bashkirtseff died of tuberculosis just before her twenty-sixth birthday, leaving the historical painting unfinished.

In 1887 the posthumous publication of an expunged version of her diary contributed to her international fame as a writer, but toned down her image as a politically committed artist who rebelled against the societal norms of her time in favour of a conventional portrait more suited to the normalised image of 19th-century women.

Publication made in partnership with musée d’Orsay.

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2021

![Paroles d’artistes femmes [Words of Women Artists], 1869-1939 - AWARE](https://awarewomenartists.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/anthologie-1-aware-women-artists-artistes-femmes-1-750x509.webp)