Marlow Moss

Schaschl-Coope Sabine (ed.), A forgotten Maverick : Marlow Moss, Berlin, Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2017

Marlow Moss, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, 30 March – 30 April 1962

→Marlow Moss 1889–1958, Tate St Ives, 2013

British painter and sculptor.

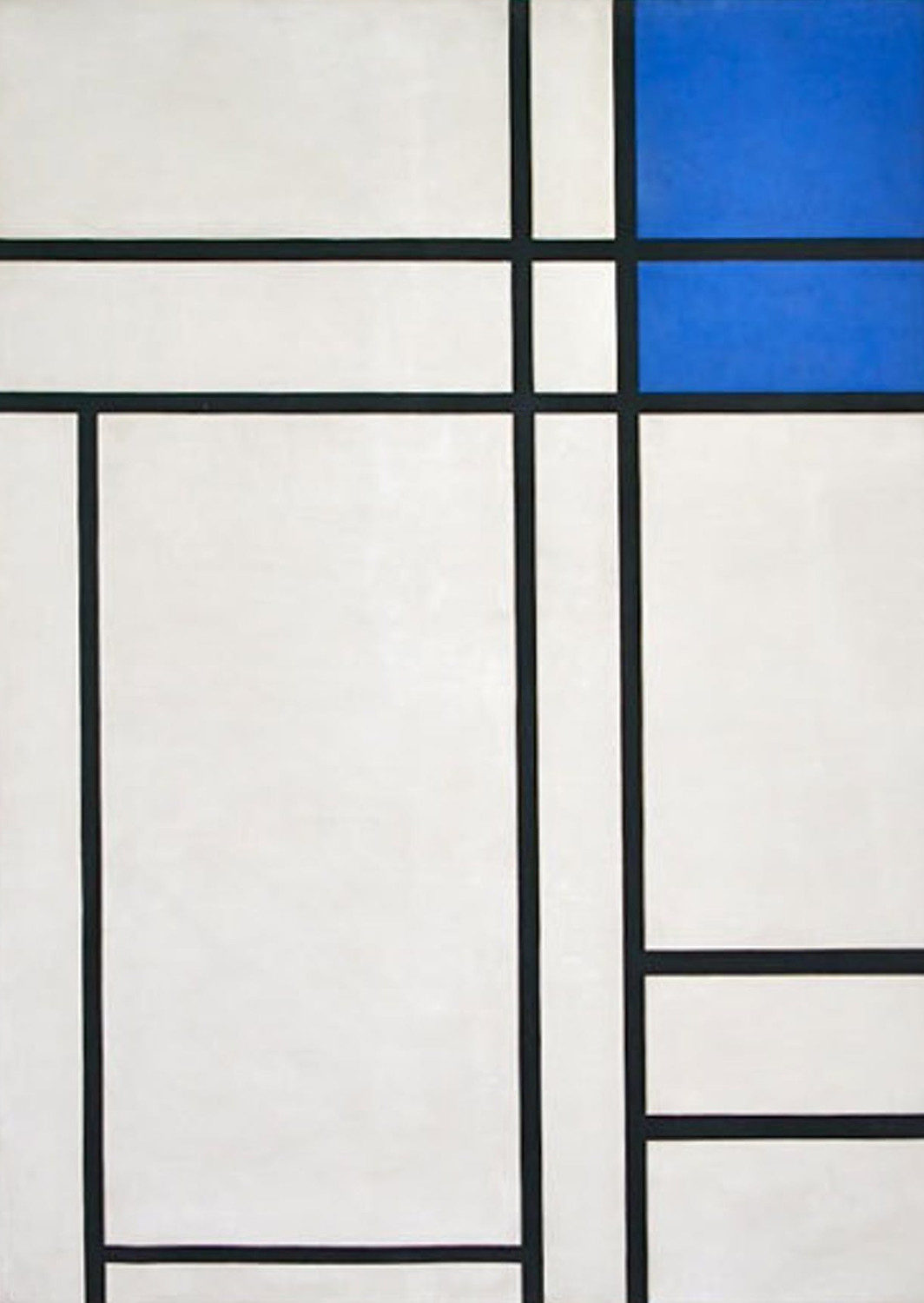

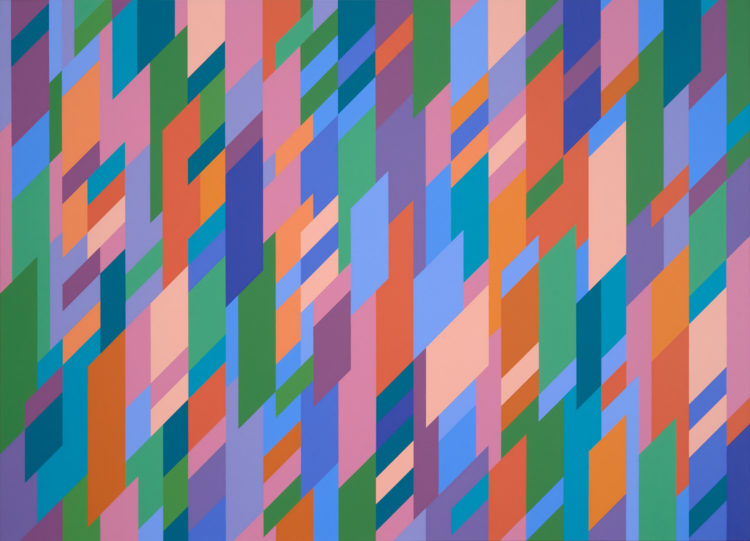

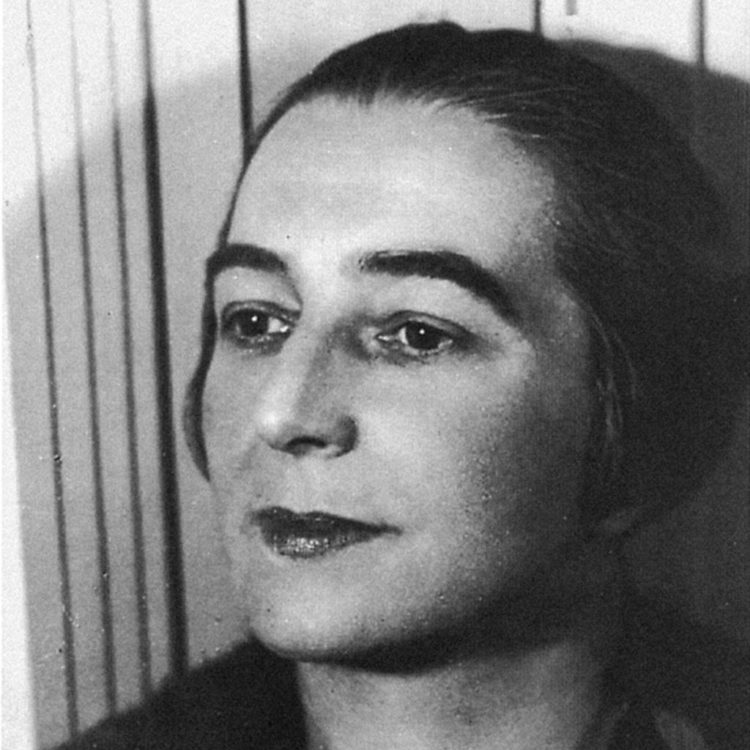

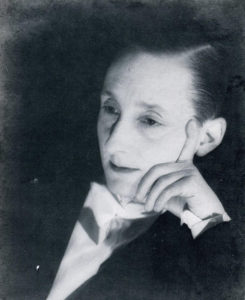

Born to an upper class family, Marlow Moss first studied piano but was forced to stop after she contracted tuberculosis. When she recovered, she turned to dance and movement. Her guardian – she had lost her father – promised her the best teachers on the condition that her artistic practice remain non-professional. She rebelled by enrolling in the St John’s Wood School of Art, later cutting off ties with her family to study at the Slade School of Fine Art from 1917 to 1919 before withdrawing to Cornwall. Upon returning to London, she shaved her head, began to wear men’s clothing and adopted a masculine name. By doing so, she became a new person whose “costume says to the man: I am your equal”, as Madeleine Pelletier famously put it (La Suffragiste, No. 46, 1919). She was self-taught, immersing herself in Rimbaud and Nietzsche at the British Museum Reading Room and studying the works of Van Gogh and Rembrandt. She arrived in France in 1927 at the age of 37; in a photograph – often published without mention of her name – she is seen wearing a tie, holding a cigarette, sporting very short, slicked-back hair and a face free of makeup. As for painting, she chose the path of abstraction. While studying at the Académie Moderne under Fernand Léger and Amédée Ozenfant, she found herself deeply impressed by a work of Piet Mondrian. She met the painter two years later, and the artists seem to have remained in contact from 1929 to 1938.

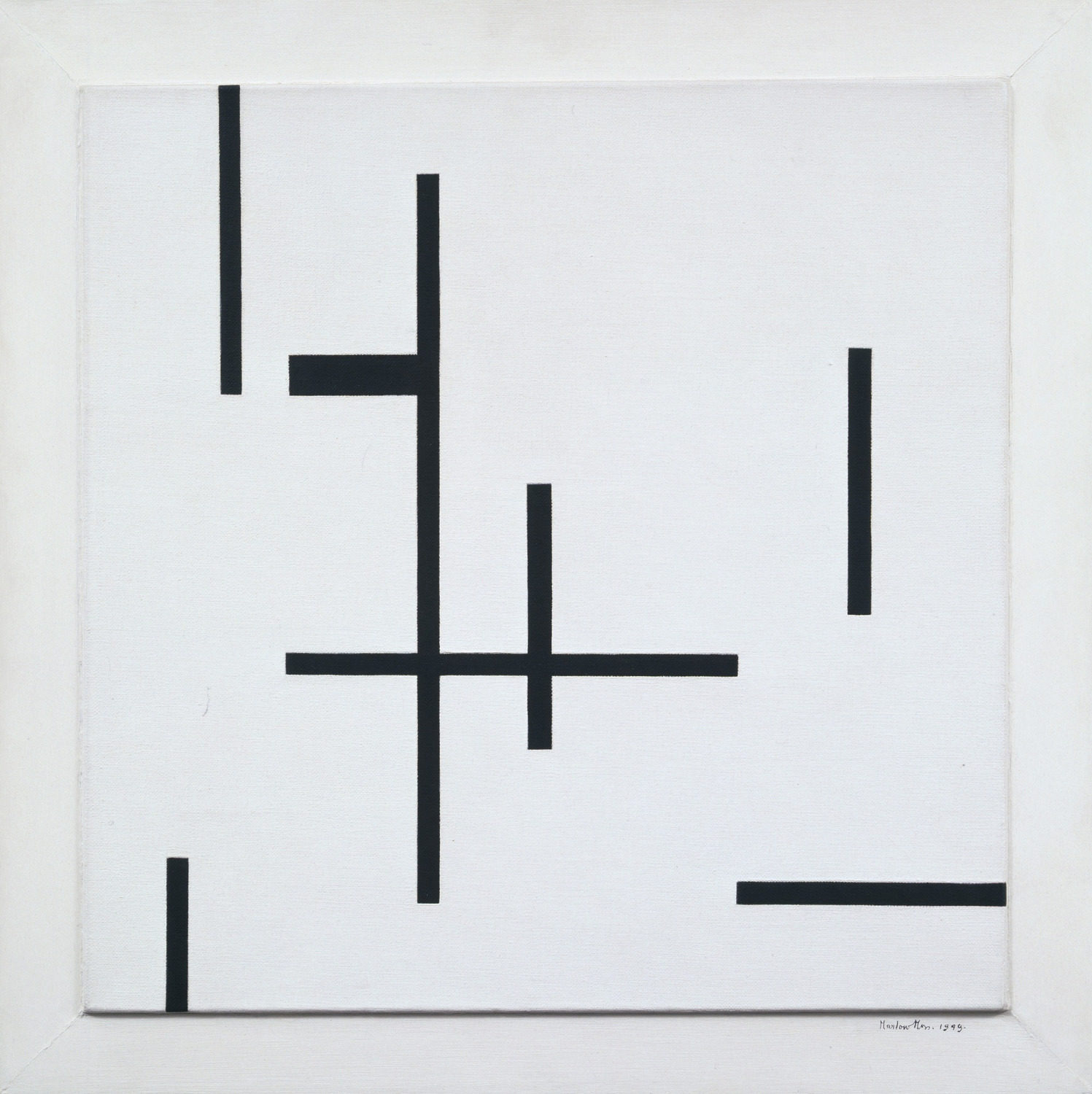

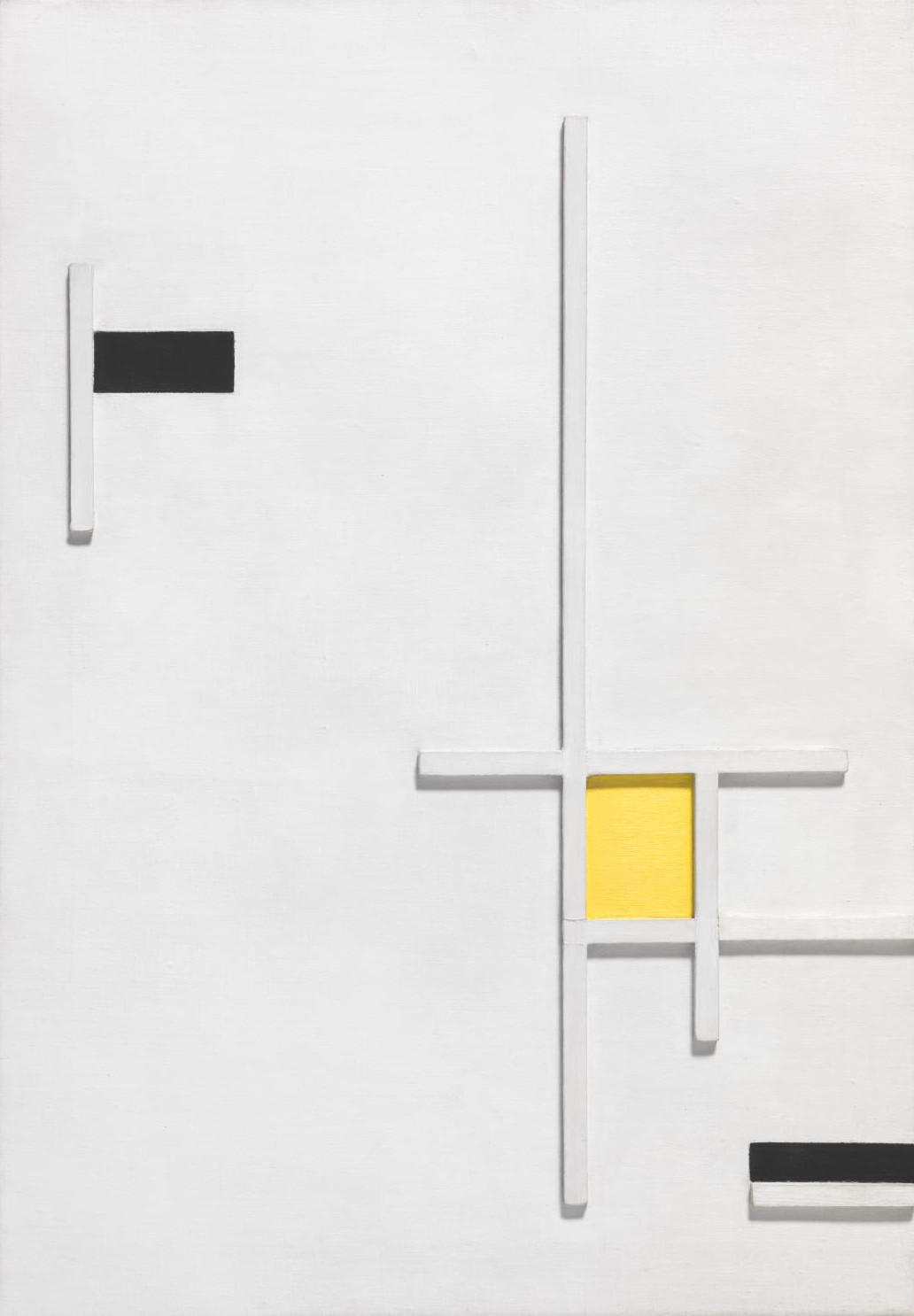

M. Moss is thought to have painted her first Neo-plasticist work in 1929: two lines intersecting at a right angle on a white background. Because P. Mondrian never taught her his pictorial technique, she is thought to have invented her own first “deviation” from the vertical-horizontal grid, which she deemed too static: the double line. Historians have noted that these types of compositions only appeared in P. Mondrian’s works two years later. M. Moss would subsequently do away with this type of structure, instead choosing to exploit as much of the white’s brightness as possible, and combining several types of monochromatic canvases to create all-white reliefs. To these, she sometimes added lines of string painted in white or bare rope to express tension, instead of using colour to do so. She became a member of the Surindépendants and of the group Abstraction-Création, and experimented in her immaculate phalanstery studio at Gauciel (known as château d’Évreux), where she and her partner Antoinette H. Nijhoff received passing artists. The studio and its entire contents would later be destroyed in a bombing. In 1939, M. Moss left France for the Netherlands. The following year, the German invasion forced her to flee by boat to England, where, an orphan and a stranger, she reluctantly took architecture classes, which sparked an interest in sculpture. Her acquaintance with a naval engineer enabled her to begin working on metal structures. She converted a small carpenter’s workshop into a studio and spent the post-war years attempting to recreate some of her lost works. Exhibitions of her work during her lifetime (Hanover Gallery, London, 1953), and after her death (Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1962) focused on rehabilitating the autonomy of her visual approach, with Germaine Greer underlining its influence on British art. In spite of this effort, M. Moss’s work is still not sufficiently recognised for its importance within interwar abstract movements.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2019

Marlow Moss at Museum Haus Konstruktiv

Marlow Moss at Museum Haus Konstruktiv