Mary Edmonia « Wildfire » Lewis

George, Alice, “Sculptor Edmonia Lewis Shattered Gender and Race Expectations in 19th-Century America”, The Smithsonian Magazine, August 22, 2019

→Roscoe Hartigan, Lynda, “Lewis, Mary Edmonia ‘Wildfire’”, in Clark Hine, Sarlene, Black Women in America, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2nd ed., 2005

→Wolfe, Rinna Evelyn, Edmonia Lewis: Wildfire in Marble, Parsipippany, Dillon Press, 1998

Edmonia Lewis and Henry Wodsworth Longfellows: Images and Identities, Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, February 18 – May 3, 1995

→Art of the American Negro Exhibition, Chicago, 1940

American sculptor.

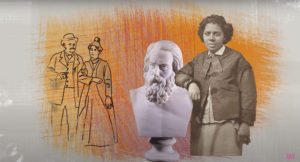

Mary Edmonia “Wildfire” Lewis, known as “Edmonia Lewis”, was the first woman of mixed-race ancestry in the United States to become an accomplished sculptor of national and international import, finding renown in Italy and England as well as at home during the Civil War era. Her marble creations are distinctive for their depictions of abolitionists icons, Native American and African American subjects, biblical themes, and portraits executed in the neoclassical style popular in the late nineteenth century. Unravelling E. Lewis’s history has been filled with enigmas and compounded by the complex realities of women working within male-centric cultures that coveted the genre of sculpture as well as the variables of the artist’s own descriptions and documented interviews.

E. Lewis was born in upstate New York in 1844. Her mother, Catherine Mike Lewis, was part Mississauga Ojibwe and was an accomplished weaver and craftswoman. Her father was African American, with the last name Lewis, whose precise identity is unconfirmed but is speculated to have been either a gentleman’s servant or a writer from the Caribbean islands. Few specifics of E. Lewis’s early life are known except that she grew up in New Jersey and that she was given the name of Wildfire. Her older half-brother, Samuel “Sunrise” Lewis, alone with two maternal aunts, helped to raise Edmonia after their parents died when she was nine years old. Samuel left the family, finding success during the California Gold Rush. When E. Lewis came of age Samuel enrolled her in the Ladies’ Preparatory Division which later became Oberlin College in Ohio.

Leaving Oberlin College after an arrest for accusations of poisoning her classmates, violent attacks, jailed and exonerated, E. Lewis moved to Boston in 1863 to pursue a career in the arts. Mentored by sculptor Edward Brackett, she was able to garner critical support from Lydia Maria Child and William Lloyd Garrison as a result of commissions and sales of portrait busts and medallions she created of abolitionists. E. Lewis became friends with the sculptors Harriet Hosmer, Anne Whitney and Charlotte Cushman who encouraged her to move to Rome where she opened a studio in 1865. She became a significant member of a group of British and American women expatriate sculptors in Italy whom writer Henry James dubbed “the White, Marmorean Flock.” E. Lewis was highly sought after for studio visits by American tourists and became popular in the Italian social scene. However she was also highly sensitized to the politics of race, class and gender, and sought to protect the integrity, authenticity and agency of her artistry. From the first cut of the marble to the final polishing, each creation was executed by E. Lewis’s own hand, as opposed to having the support of studio assistants, fearing that her work might be attributed to male assistants.

E. Lewis’s active years of 1865-1876 were marked with the creation of critical works that focused on issues of liberation. Forever Free (1867), inspired by the words of Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation that ended slavery in the United States, is in the Howard University Gallery of Art. This is the earliest known work by an American artist depicting imagery of freed African Americans. Given the grave plights of women of color globally, in E. Lewis’s The Death of Cleopatra (1876), in the collection of the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, suicide can be viewed as an act of personal liberation – depriving male entities of power control over the timing Cleopatra’ execution. The aesthetic and political visions of E. Lewis are bold, fearless, and courageous statements, and there is estimated to be a body of nearly sixty works in existence, less than half of which have been located.

A biography produced as part of “The Origin of Others. Rewriting Art History in the Americas, 19th Century – Today” research programme, in partnership with the Clark Art Institute.

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2022

Art History Series: Edmonia Lewis | Northwest Regional Library System, Florida, 2021

Art History Series: Edmonia Lewis | Northwest Regional Library System, Florida, 2021  Edmonia Lewis | Walker Women | National Museum Liverpool, 2021

Edmonia Lewis | Walker Women | National Museum Liverpool, 2021