Mathilde Létizia Wilhelmine Bonaparte

Bonaparte Mathilde Letizia Wilhelmine, Mémoires inédits, Paris, Grasset, 2019

→Des Cars Jean, La Princesse Mathilde : l’amour, la gloire et les arts, Paris, Perrin, 2006

→Bonaparte Mathilde Letizia Wilhelmine, Flaubert Gustave, Lettres inédites à la Princesse Mathilde, Paris, Louis Conard, 1927

Un soir chez la Princesse Mathilde, une Bonaparte et les arts, Palais Fesch, Ajaccio, June – September 2019

→La princesse Mathilde et son temps, Palazzo Strozzi, Florence, 1959

French watercolourist.

Mathilde Bonaparte was the daughter of Jérôme Bonaparte, Napoleon’s brother, and of Catharina of Württemberg. She was born in Italy, where her family lived in exile after her father’s short reign as the king of Westphalia (1807-1813) and the fall of the emperor. The young princess was taught ornamental arts, such as drawing and tapestry, and also took painting lessons from Michel Ghislain Stapleaux (1799-1881), a student of Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), and from Florentine artist Ida Botti Scifoni (1812-1844). In 1840 she married Russian aristocrat Anatoly Demidov, whose villa in San Donato, near Florence, was home to a large art collection. M. Bonaparte visited Italian museums, made copies of the works she saw there and spent time in artists’ studios before moving to France in 1846. Her separation from Prince Demidov was announced by the Tsar in 1847. Meanwhile, the princess had entered a new relationship with sculptor Émilien de Nieuwerkerke (1811-1892), who would go on to play a decisive role in the imperial administration of the arts – in part thanks to her. M. Bonaparte promptly surrounded herself with a large literary and artistic circle, creating a form of patronage through the purchase of works and financial backing, which owed as much to her official duties as a member of the imperial family as to her personal taste. She was, indeed, one of the rare women collectors during the 19th century in France, years before Nélie Jacquemart-André (1841-1912).

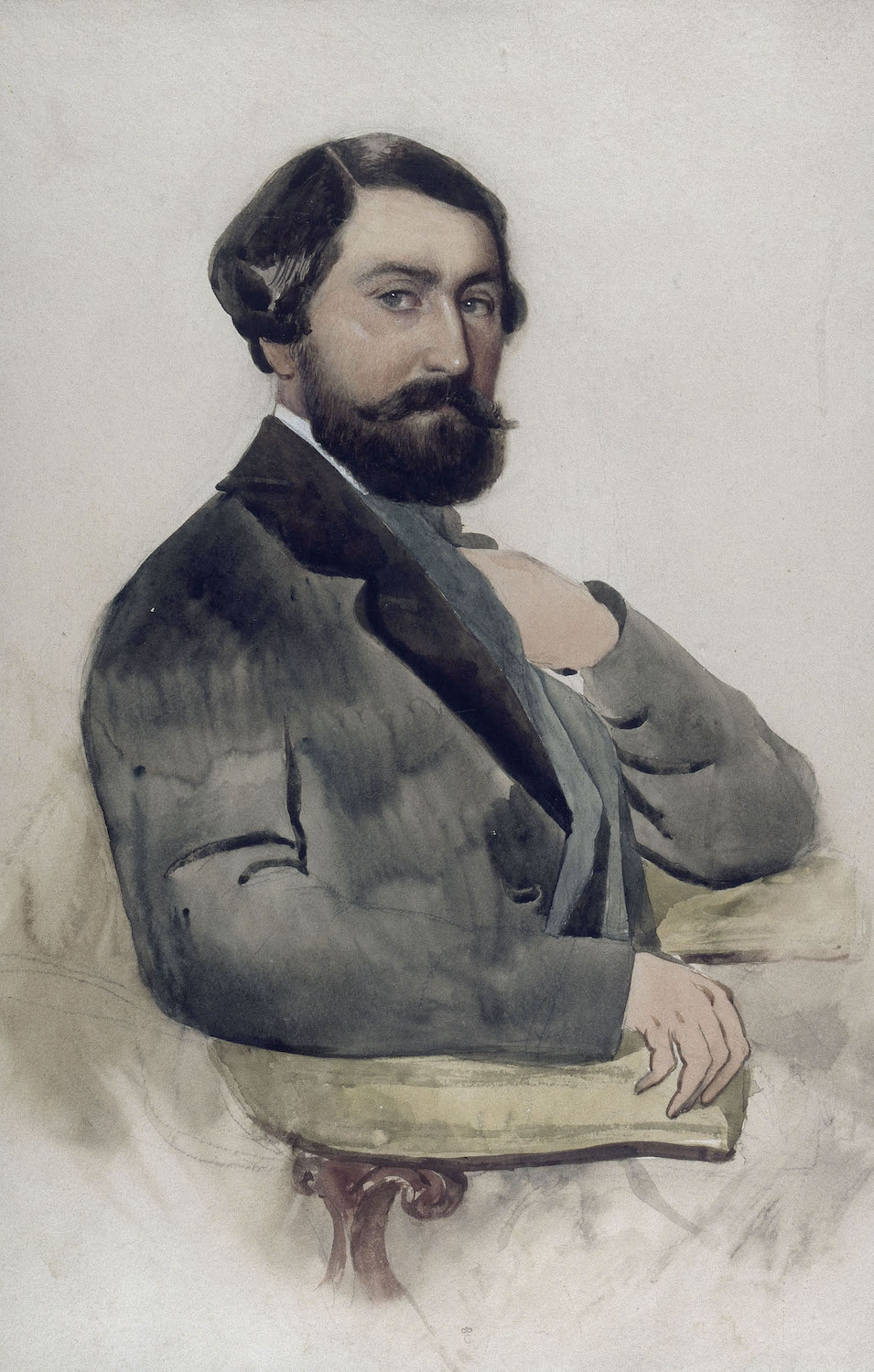

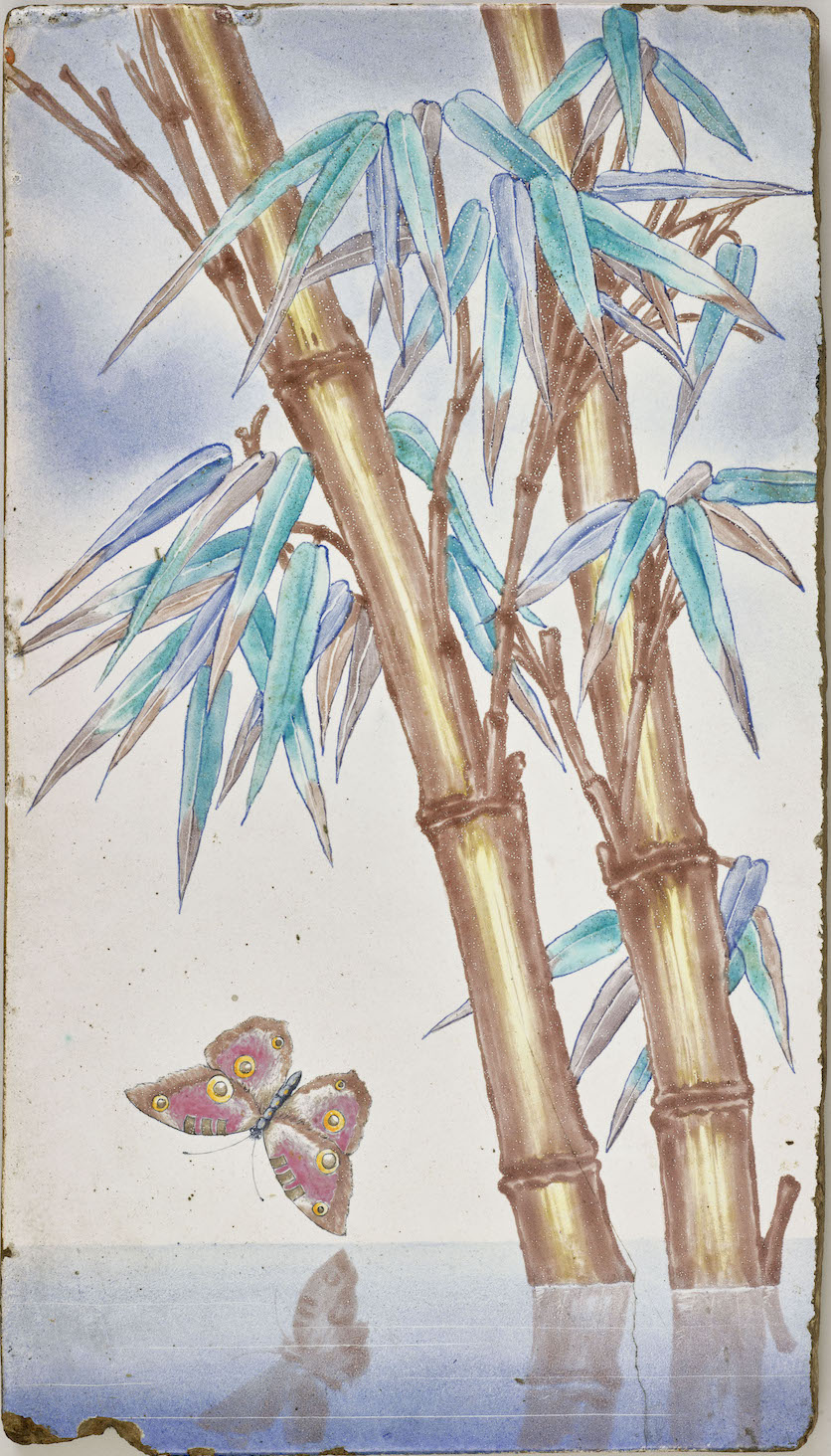

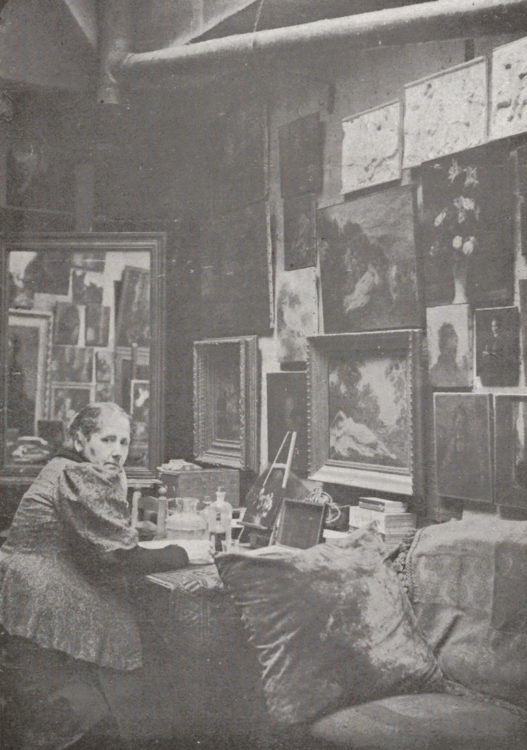

More than a salon-goer and collector, the princess was depicted and depicted herself mostly as an artist. She produced mainly drawings and watercolours but continued to take lessons from masters throughout her life – an indication of her training as an amateur painter –occasionally from Ernest Hébert (1817-1908), and more often from Eugène Giraud (1806-1881), one of her closest friends, whom she mentioned as her teacher at the Salon, where she exhibited under her own name from 1859 to 1867. M. Bonaparte’s subjects were predominantly imaginary figures dressed in costumes inspired by the historicist and orientalist trends in fashion at the time, painted in relatively large formats, such as Une fellah (1861 Salon), Tête d’étude, d’après nature (Study of a head, from nature], also known as Orientale (1864), and Juive d’Alger [Jewish woman of Algiers, 1866 Salon]. In doing do, she distinguished herself from other women artists of her time, who were often reduced to painting copies or still lifes, instead favouring character work and painting from nature, for which she often had young women pose – sometimes in the nude – in her Parisian studio or at her countryside property in Saint-Gratien. However, she also conformed to expectations relating to her “sex” by presenting copies of the masters and painting floral and bird motifs on fans and screens. In 1869 she created a large silk painting for the Goncourt brothers to decorate the ceiling of their house in Auteuil (today lost). The princess received two honourable mentions and a third-class medal in 1865. Commentators in the press lauded her for the “virile” quality of her style, which rivalled oil painting and enabled her to evade the characteristics usually attributed to “feminine art”. In private, opinions were often more condescending: Edmond de Goncourt, after watching the princess at work, said of her that she “daubed” like a child (Journal, 5 November 1874).

As an independent woman – both maritally and financially – a fierce guardian of her family’s legacy and a free thinker, M. Bonaparte led a relatively liberated life in the company of artists, which made her the target of anti-Bonapartist caricatures in 1870-1871. Putting aside aesthetic considerations, she appears as a major figure of the art world at the time due to the importance of her salon and collection, her determination to elevate herself as an artist above her status as a dilettante and to treat traditionally “masculine” subjects, as well as for her influential position in French public life and society.

Despite some recent acquisitions of her works by the Musée Hébert in Paris (a public institution of the Musée d’Orsay and Musée de l’Orangerie) and Musée Fesch in Ajaccio, most of M. Bonaparte’s works currently held by French public collections were donated by the artist. The princess also donated several pieces from her collections to national museums, including a marble bust by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (1827-1875) and a pastel portrait of herself as a painter by Lucien Doucet (1856-1895).

Publication made in partnership with musée d’Orsay.

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2021

Conference, Princesse Mathilde et Saint-Gratien | Archives du Val-d’Oise (french)

Conference, Princesse Mathilde et Saint-Gratien | Archives du Val-d’Oise (french)  Bicentenary of Princess Mathilde’s birth | Ville de Saint-Gratien (french)

Bicentenary of Princess Mathilde’s birth | Ville de Saint-Gratien (french)