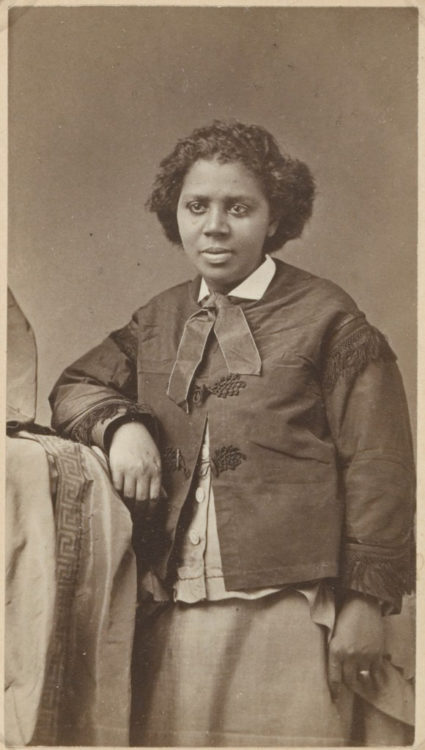

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller

Lantin, Gaëlle, Black sculptors during the Harlem renaissance: artists or more than that? : the examples of Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller and Richmond Barthé, thesis (master 2) under the supervision of Alain Michel Geoffroy, Université de la Réunion, 2016

→Ater, Renée, Remaking race and history : the sculpture of Meta Warrick Fuller, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2011

→Koontz, Shonnette, A collection of the life and work of Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, 1877-1968, Institute, WV, West Virginia State College, 2003.

The Witch’s Cradle : Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, Central pavillon, Venice biennial , April 23 – September 29, 2022

→Meta Warrick Fuller: From the Studio, Danforth Museum, Framingham State University, November 22, 2008 – May 17 2009

→An independent woman: the life and art of Meta Warrick Fuller (1877-1968), Danforth Museum of Art, Framingham, Massachusetts, December 16, 1984 – February 24, 1985

American sculptor.

At times when Black women artists were rarely given the opportunity of a proper training in the visual arts and sculpture was considered a man’s world, Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller became a pioneering sculptor whose work wrapped in symbolism introduced African subjects and depicted the Black experience ahead of her contemporaries. Born during the Jim Crow era of racial segregation into a middle class African-American Philadelphia family in 1877, M. Fuller’s barbershop-owning father and hairdresser mother were able to encourage her artistic abilities and provide her with an education in the arts. At a young age she was overwhelmed by sculptures while visiting art exhibitions and was inspired by ghost stories and tales of horror. At the age of 17 she won a three-year scholarship to attend the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art before travelling to Paris.

The artist studied sculpture and drawing in France from 1899 to 1902. She enrolled at the Académie Colarossi and the École des Beaux-Arts and showed her works in major exhibitions. In the French capital she was mentored by expatriate African-American painter Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937) who introduced her to the Parisian art world. She also met Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), who praised and encouraged her to continue creating her sculptures. She was named the “sculptor of horrors” in the French press due to her depiction of deepest human emotions in pieces such as Man Eating His Heart (1901) and The Wretched (1902). While her time in Paris was full of opportunities for her artistic career, upon her return to Philadelphia, M. Fuller was met with rejection from the city’s art dealers due to racial and gender discrimination and had to struggle to exhibit and sell her art.

At the Exhibit of American Negroes during the 1900 Paris World’s Fair, M. Fuller made an important connection with African-American scholar and civil rights activist W. E. B. DuBois who worked to elevate Black culture in America and later provided her with major sculptural commissions. In 1907 M. Fuller was the first African-American woman to receive a US federal art commission when W. E. B. DuBois invited her to produce a piece to mark the Jamestown Tercentennial Exhibition. Named the Warrick Tableaux, it consists of a series of dioramas chronicling the history of the Black community. W. E. B. DuBois called on the sculptor again in 1913 to create Emancipation, a group of life-size figures commemorating the 50th anniversary of the abolition of slavery for the National Emancipation Exposition. One of her most forceful works was the allegorical sculpture Ethiopia Awakening, also commissioned in 1921 for the America’s Making Exposition in New York City.

In 1909 she married Dr Solomon Carter Fuller and the couple moved to Framingham, Massachusetts in 1910. That same year sixteen years of her art was destroyed in a fire that broke out in her warehouse. She afterwards tried balancing her art career with her husband’s expectations to settle in her role as a wife and mother of three children. Working in bronze, plaster and wax, her subject matters expanded from human trauma, African heritage, racial and social injustices to intimate portraits and religious themes.

After her husband’s death and towards the end of her life in the 1960s, M. Fuller started writing poetry that reflected her life. She is considered a forerunner of the flourishing Harlem Renaissance and inspired other sculptors such as Augusta Savage (1892-1962) and Nancy Elizabeth Prophet (1890-1960). The Danforth Art Museum at Framingham State University holds the largest collection of her art.

A biography produced as part of “The Origin of Others. Rewriting Art History in the Americas, 19th Century – Today” research programme, in partnership with the Clark Art Institute.

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2023