Research

Aché woman with nakó, 2007, Mbarakayú Reserve in the department of Canindeyú, © Photo: Fernando Allen.

Texture and fibre. Landscape Writing and Relationships of Dependency: Plant Fibre Availability and Sustainability in Aché and Nivacché Women’s Artistic Practices and Processes in Paraguay.

Women gatherers introduce their knowledge of materials into a world while also extracting fibres from it. Functions and meanings blur and overlap when utilitarian textiles also express symbolic ideas. In Paraguay, Aché and Nivacché women combine plant fibres with vegetable and mineral dyes, feathers, and animal and human hair to create contrasts and juxtapose oppositions. Using these fibres and other materials, they make fabrics and objects which sometimes take on animal forms, decorating them with repeated graphic and chromatic patterns. The fabrics also visually translate the surrounding landscape, not just in the woven patterns, but also via the materials representing the life which thrives there.

Dyeing caraguatá yarn, 2011, process of dyeing caraguatá fiber, Nivaclé community of Colonia 9, Boquerón, Paraguayan Chaco, © Photo: Fernando Allen

But how does one tell the story of a landscape when it has been so dramatically altered? Nivacché artist Siovsa Felicia Segundo de Valeriano talks about the status of her ancestral lands: ‘I was born in Tinjoque,’ she says, ‘a place which is now occupied by Estancia Margarita in the area known as General Díaz’.1 The name of the place she was born has thus changed, as has the landscape, but she was still able to learn a range of designs handed down by generations of women: ‘First I learned the design of the cactus fruit (sôtôvai), then the jaguar’s footprint (yiyôôj lhaishivo) and the design of the rattlesnake (ôclônilh)’.2 Weaving and basketry functions much like the act of writing, creating a testimony of the landscape’s existence and narrating the world’s ability to give birth to forms which, in turn, enable the existence of forms of life and their relationships with the world.

In the indigenous communities of Paraguay, weaving and basketry have historically been women’s practices. In spite of colonisation and its effects, including intensive land use, changes marked by extractivism, and the disappearance of traditional modes of farming and subsistence, these practices have nonetheless survived. Traditional income-generating activities such as these offered the ideal conditions for the creation of baskets and bags by indigenous artists, but since the material conditions of life have changed, these objects’ functions and, in some cases, materials, have also altered. Along with this comes a transformation of the cultural patterns and social rituals which are expressed through textile bags and baskets – they now narrate the alteration of the landscape and the materials it provides to these communities.

Clisá, 1990, bag for commercial use made of caraguatá fiber, dyed with natural and industrial dyes, 44 × 40 × 43 cm, Nivaclé community of the Paraguayan Chaco, Centro de Artes Visuales/Museo del Barro, © Photo: Susana Salerno and Julio Salvatierra

In conveying the changes made to the land, the patterns woven into textiles and baskets have taken on new meanings and functions. Utilitarian functionality can also express beauty, but when the original uses of an object disappear, its shapes survive as symbolic designs or remnants of their ancestral culture as well as instruments of communal and individual affirmation. Aché and Nivacché women’s textiles and baskets are now displayed and sold in galleries, museums, stores, and fairs, and have become attractive consumer products for both local and international buyers.

The sustainability of Aché and Nivacché women’s traditional artistic practices depends on the biological availability of natural resources. These practices are, therefore, linked to access to the landscape. Colonisation and displacement lie behind the loss of their territory. Although these territories have been continually deforested over the 20th century, this process has dramatically increased over the past two decades due to intensified cattle ranching in the Chaco region and soya bean cultivation in the Atlantic Forest area of the Alto Paraná. Every time a bulldozer clears out another part of their territory, a few more meters of forest are lost. Paraguay ranks among the top two Latin American countries in terms of per-day deforestation rates and, in certain seasons, is no. 1.3 This deforestation destroys ecological habitats, leading to an increased number of endangered animal and plant species.

Anthropologist Ursula Regehr has identified 279 endangered plant species. Moreover, the few reforestation projects in the region introduce exotic species which threaten biodiversity by replacing local species.4 A threatened but not yet endangered plant species, the caraguatá (from the Bromeliaceae family), is an essential raw material which the Nivacché use to make thread from which they weave bags called clisá with a variety of designs.

Clisá, 1997, bag for commercial use made of caraguatá fiber and dyed with natural and industrial dyes, 27.5 × 100 × 28 cm, Nivaclé Community of Filadelfia, Paraguayan Chaco, Centro de Artes Visuales/Museo del Barro, © Photo: Susana Salerno and Julio Salvatierra

These textiles are closely related to the traditional economy, which is based heavily on hunting, fishing, and gathering5 – all practices which are now restricted in Chaco communities. According to anthropologist Miguel Chase-Sardi, women have always played the main role in gathering and were also the guardians of bags used to store and carry food and cooking utensils.6

But traditionally gathered foods have been replaced by mass-produced products, and traditional containers – textile bags – have also been crowded out by industrial ones. And today, Nivacché women make plant-fibre textiles primarily for the purpose of selling them. Along with these shifts, gathering activities have decreased and fewer of the items used for this work have been made. As Regehr explains, ‘This transformation results in the gradual restriction of the practices of sharing and giving.7

Slovenian-Paraguayan anthropologist Branislava Susnik has researched the persistence of Nivacché textile production during colonisation in the 20th century despite this decrease in use. According to Susnik, although textiles are produced for utilitarian purposes, they are not linked to them exclusively.8 But when it became difficult to move through the caraguatá fields, young women, already in the process of subjecting themselves to the colonisers’ culture, began to view traditional practices with disdain.9 External interest, together with an increasing desire for cultural affirmation, has however brought about a return to certain practices in the communities. The production of bags has also resumed due to their market value as handicrafts or popular art (albeit always from the perspective of Western civilisation).

Woven in a rectangular shape, clisá bags made by Nivacché women feature traditional geometrical ornaments. Some hexagonal shapes resemble animal skin, shells, and even footprints. The bags are sometimes made to resemble extinct or rare species.

Kromi pia, 1997, ellipsoidal band for carrying babies, made of pindó, samu’ũ and wild nettle, 42 × 68 cm, Aché community of Yñarõ, Centro de Artes Visuales/Museo del Barro, © Photo: Susana Salerno and Julio Salvatierra

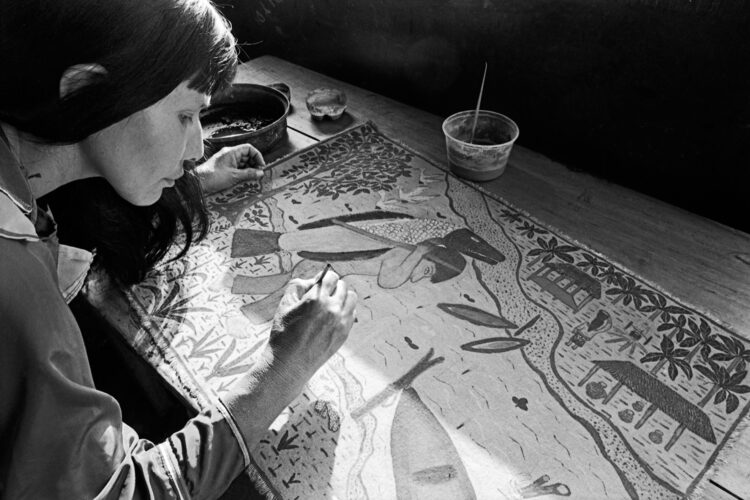

Aché women weave bags and baskets from threads made from a range of materials. Ticio Escobar notes that these include fibres from coconut and pindó palms (queen palms), ortiga brava (stinging nettles), guembepi (Philodendron), beeswax, samu’ũ fibres (Chorisia speciosa), takuarembo (Chusquea ramosissima), monkey and human hair, and charcoal. By combining these different materials, they create contrasts of colour, texture, and function and sometimes make the items primarily for decorative purposes. B. Susnik notes that ‘women, good basket makers, are held in high esteem in the community.10 Likewise, in the Aché culture, each piece is associated with a specific use. Artist and writer Ysanne Gayet cites examples of various creations from Puerto Barra, Alto Paraná: pia’a (baby carrier), nako (large basket carried using a forehead band), rawe (pindó mat), ewichã (small cylindrical basket), güene (hood made of mixed fibres), and deity (liquid container).11

Deití, 1970, vessel-basket with vegetable fibers, charcoal, and beeswax, 31 × 27 cm diameter, Aché community of Yñarõ, Centro de Artes Visuales/Museo del Barro, © Photo: Susana Salerno and Julio Salvatierra.

Traditionally, Aché society has been divided by gender: men were hunters, while women were basket bearers.12Aché women were responsible for making the baskets they used to collect and transport fruit, tubers, and worms, and also to carry children. However, access to the land and raw materials has diminished. As the Aché artist Teresa Karepakãpukúgi observes, the making of rawe (pindó mat), which once had large dimensions, is now restricted by deforestation, which exposes pindo to too much sun, creating a scarcity of young pindó palm fibres. As Fostervold notes, “because of the strong sun . . . [they] fall apart.13

Threats to biodiversity compound the erasure of cultural practices caused by colonisation and the neo-colonial structures which have led to the genocide of Aché people, and in some cases the sexual enslavement of Aché women. Today’s existing communities are formed of survivors of these processes. Cultural exchanges have sprung up between different Aché groups which share the same history of traditional practices and knowledge being forcibly erased. Fostervold gives the example of Aché artist Alicia Tokangi, who was born in a silvicultural context but grew up under the neo-colonial regime. Although her survival did not depend on basket weaving, she nevertheless learned the craft. ‘Even so,’ writes Fostervold, ‘there are certain traditions that she too did not learn or has forgotten.14

Ravé, 1990, pindó palm mat, 98 × 221 cm, Aché community of Yñarõ, Centro de Artes Visuales/Museo del Barro, © Photo: Susana Salerno and Julio Salvatierra

This ecocide has drastically altered the landscape. Biodiversity loss has led to the disappearance of game and products collected by women, both of which were the basis of the Aché diet. At the same time, their diet has been affected by acculturation processes. This has both practical and ethological consequences: the lack of raw materials makes it difficult to create pieces, while the functions are reduced as they cannot be used in traditional ways and industrial utensils have displaced traditional ones.

The nako basket, used to carry fruit and children, features different shades of green which form lines reminiscent of those in the traditional Aché territory: the forest, interrupted by clearings, and the river. The scarcity of materials and loss of the territory also translate to lines and narrate alternative forms of history.

Clisá, 1997, bag for commercial use made of caraguatá fiber with natural and industrial dyes, 22 × 100 × 23.5 cm, Nivaclé community of the department of Boquerón, Paraguayan Chaco, Centro de Artes Visuales/Museo del Barro, © Photo: Susana Salerno and Julio Salvatierra

But Aché and Nivacché weavers and basket-makers do not only visually translate the landscape, or, in other words, write the landscape, creating schematic or even figurative forms. They also transpose space itself onto fabric via geometric patterns and shapes made of fibres, dyes, hair, feathers, or minerals collected from the landscape. The space is already there when they use their bags and baskets to gather fruit from it. Women have always been an important part of their communities’ economic sustainability, and, within these new conditions which the economy has created for them, these forms of writing have clearly not lost their cultural significance. They sometimes even feature updated imagery, for example figurative representations of introduced species, colonists with guns, and industrial artifacts.

Some of these pieces are made with synthetic materials as a response to the difficulty of accessing plant fibres. The choice to use them can be interpreted not only as a marker of loss but also as the survival of a culture which refuses to disappear along with the landscape, instead asserting itself in a context dominated by other materials.

Regher, Úrsula, Simetría/asimetría: Imaginación y arte en el Chaco, Asunción: Fotosíntesis, 2011, p. 26.

2

Ibid.

3

Pechinski, Ashley, ‘Deforestación massiva en Paraguay arrasa con parques nacionales’, InSight Crime, 26 August 2021, https://es.insightcrime.org/noticias/deforestacion-masiva-paraguay-arrasa-parques-nacionales/

4

Regehr, Úrsula, Reconfiguraciones: Vida chaqueña en transición, Asunción: Fotosíntesis, 2018, p. 157.

5

Regher, op cit., 2011, p. 16.

6

Chase-Sardi, Miguel, ¡Palavai Nuu!: Etnografía Nivacle, vol. I, Asunción: CEADUC, p. 568.

7

Regehr, Úrsula, op cit., 2018, p. 34.

8

Susnik, Branislava, Artesanía indígena: Ensayo analítico, Asunción: Asociación Indigenista del Paraguay, p. 21.

9

Ibid.

10

Susnik, Branislava, Los aborígenes del Paraguay, vol. IV, Cultura Material, Asunción: Museo Etnográfico Andrés Barbero, p. 185.

11

Fostervold, Brian & Fostervold, Reinar, Catálogo de artesanos Aché de la Cuenca del Río Ñacunday/Catalogue of Aché Artisans of the Ñacunday River, Puerto Barra, p. 2.

12

Clastres, Pierre, Crónica de los indios guayakís: Lo que saben los aché, cazadores nómadas del Paraguay, Alberto Clavería (trad.), Barcelona: Alta Fulla, p. 202.

13

Fostervold, op cit., p. 25.

14

Ibid. pp. 28-29.

Lia Colombino has a Master’s degree in museology from the University of Valladolid (2002) and is currently pursuing a PhD in art at the Universidad Nacional de las Artes in Buenos Aires. She has been the director of the Museo de Arte Indígena at the Centro de Artes Visuales/Museo del Barro since 2008. She has also coordinated the Seminar Espacio/Crítica. In addition to these roles, she is the director of the Instituto Superior de Arte, Universidad Nacional de Asunción, where she teaches as well. She has curated exhibitions and coordinated literary projects.

Damián Cabrera has a Master’s degree in philosophy from the University of São Paulo. He is the coordinator of the Department of Documentation and Research at the Centro de Artes Visuales/Museo del Barro. He also teaches at the Instituto Superior de Arte, Universidad Nacional de Asunción and the Universidad Columbia del Paraguay. He is additionally an author, having published two books: Xiru (2012) and Xe (2019). He has curated art exhibitions in Paraguay.

An article produced as part of “The Origin of Others” research programme, in partnership with the Clark Art Institute.

Lia Colombino & Damián Cabrera, "Plant fiber in the artistic practice and processes of Aché and Nivacché women in Paraguay." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/texture-et-fibre-ecriture-du-paysage-et-relations-de-dependance-disponibilite-et-durabilite-de-la-fibre-vegetale-dans-la-pratique-et-les-processus-artistiques-des-femmes-ache-et-nivacche-au-paraguay/. Accessed 9 July 2025