Niki de Saint Phalle

Morineau Camille (dir.), Niki de Saint Phalle, 1930-2002, exh. cat., Grand Palais, Paris (17 September 2014–2 February 2015), Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (27 February–11 June 2015), Madrid / Bilbao, La Fabrica / Guggenheim Museum, 2015

→Francblin Catherine, Niki de Saint Phalle, la révolte à l’œuvre, Paris, Hazan, 2013

→Niki de Saint-Phalle, exh. cat., Musée d’Art Moderne et d’Art Contemporain, Nice (17 March–27 October 2002), Geneva / Nice, Musée d’Art moderne et d’Art contemporain, 2002

Niki de Saint Phalle, 1930-2002, Grand Palais, Paris, 17 September 2014–2 February 2015; Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, 27 February–11 June 2015

→Niki de Saint-Phalle, Musée d’Art Moderne et d’Art Contemporain, Nice, 17 March–27 October 2002)

French-American visual artist.

Niki de Saint Phalle spent the first three years of her life in France, then moved to New York with her parents. At the age of 11, she was molested by her father; she disclosed this her 1994 book My Secret (Mon Secret), and continued to explore the event’s aftermath in her 1999 follow-up Traces. She became a rebellious teenager and found solace in writing. She married author Harry Mathews in 1950, with whom she had a son and a daughter. The couple moved to Paris in 1951, where Saint Phalle studied theater. She stopped abruptly in 1953 due to a terrible episode of depression, during which she began painting as therapy. In 1959, she discovered the New American painters—Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns—which proved to be a profound revelation. The following year, she separated from Mathews, who maintained custody of their children, and moved in with the artist Jean Tinguely.

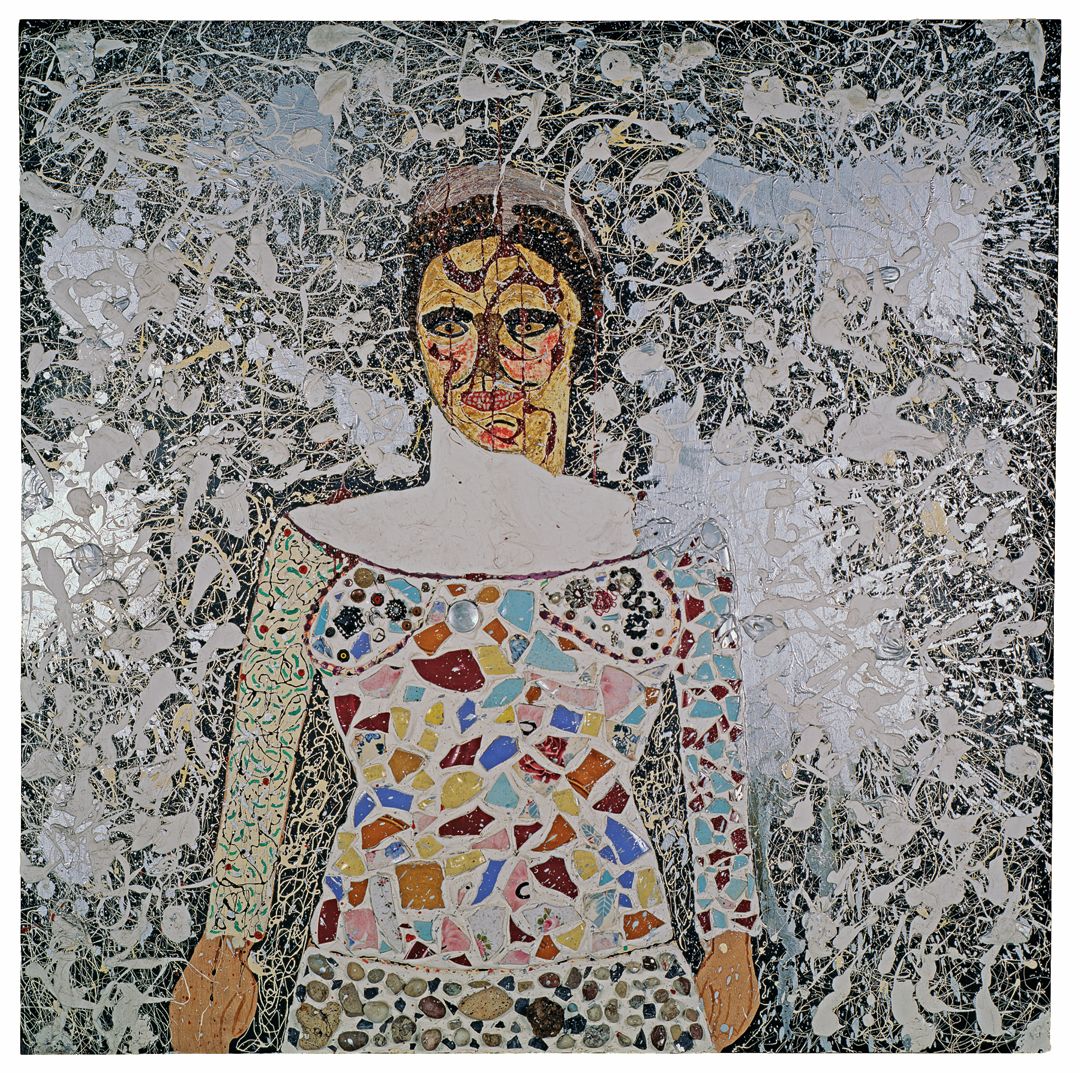

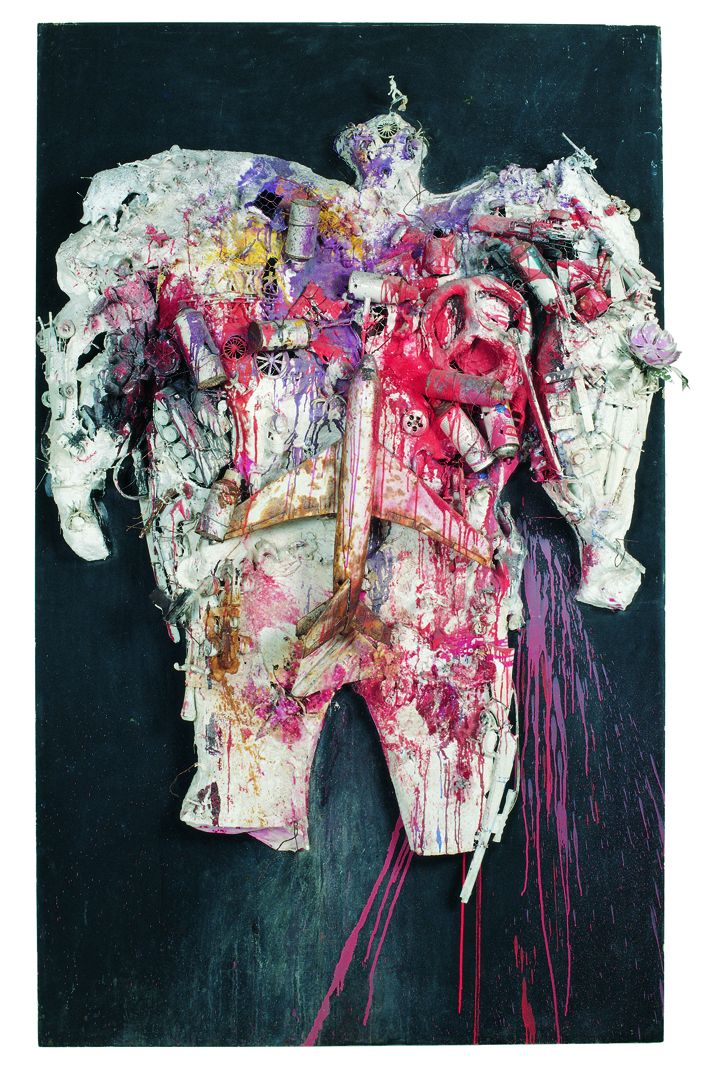

In 1961, at the Comparaisons salon in Paris, she exhibited Portrait of My Lover, an assemblage built on a target, at which viewers were invited to test their dart-throwing skill. She also created plaster sculptures that included pouches of pigment, which she exploded by shooting at them with a rifle. February 12th of that year, she organized the first of her shooting performances, which would continue from 1961 into 1962. This process was stunning, shocking, and quickly drew media attention. Swedish art collector Puntus Hulten bought some of her pieces then presented them in important European exhibitions. Saint Phalle joined the Nouveaux Réalistes group as the only female member. Thanks to her participation in a project with Johns, Rauschenberg, and Tinguely, she was accepted by the era’s artistic avant-garde, which was heavily masculine. Bit by bit, she worked to tear down traditional representations of women, and deconstructed classic archetypes—the witch, the man-eater, the young wife—all slowly crept into her work. Her sculptures are a conglomeration of everyday objects and junk, indicative of the consumer-centric society that was burgeoning in those years.

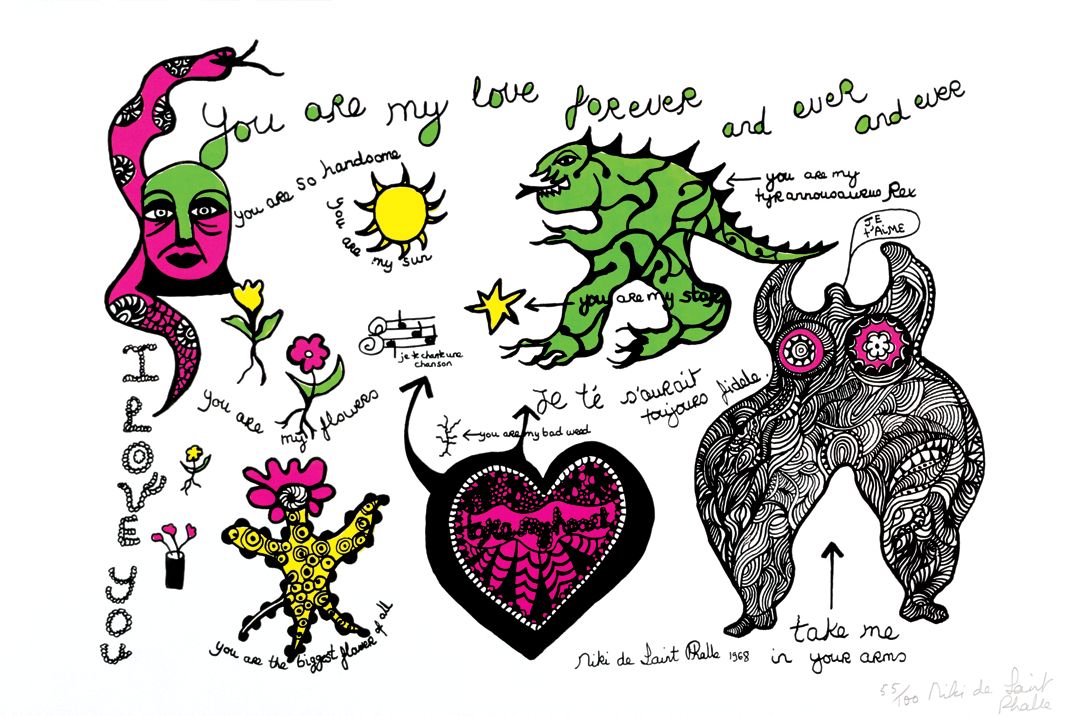

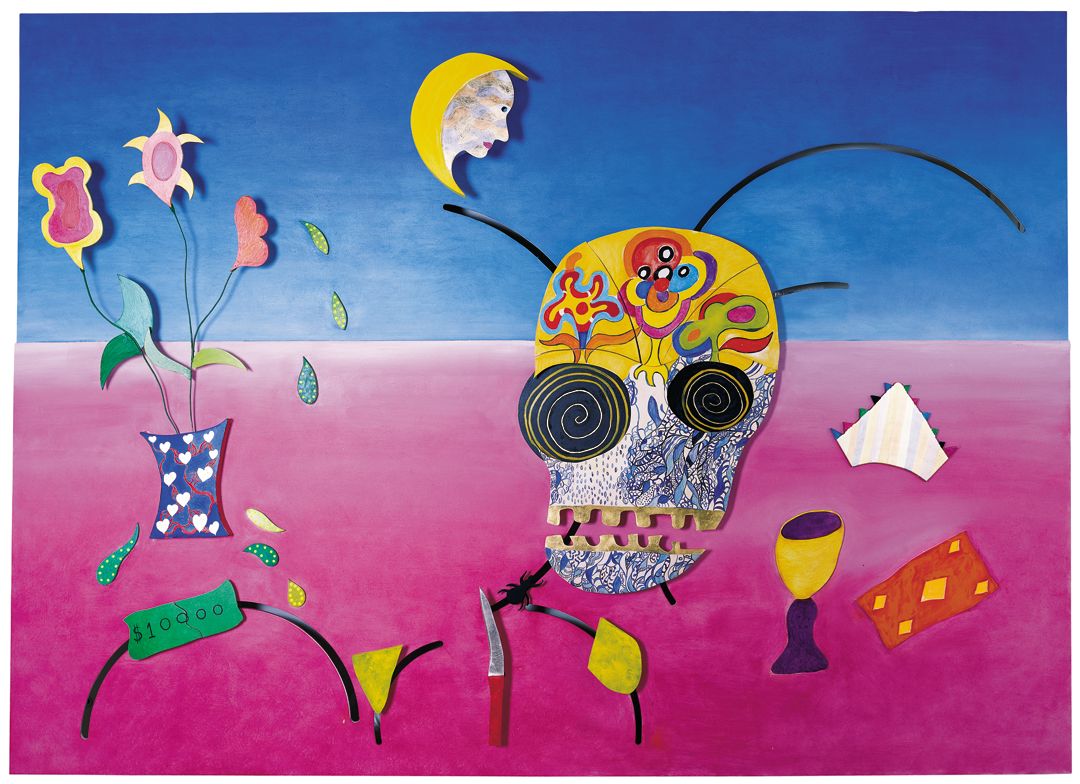

In 1964, in London, she exhibited brides, woolen heads, and dragons, and, the following year, her famous Nanas came on the scene. They were at first sculpted of yarn, papier mâché and bits of metal, but already in Saint Phalle’s characteristically vibrant colors. In 1966, she collaborated on the sets and costumes for the Roland Petit ballet Éloge de la folie (The Praise of Folly). She also exhibited Hon-en katedral, a giant (28 meters long) nana statue, which the visitor could enter through a gaping hole between her legs, and which she installed in Stockholm with Tinguely, Per Olof Utvedt, and Rico Weber. This work poked fun at the institution of museums, for which the female body becomes the object of all sorts of mistreatment, and proclaimed the power of the feminine. In 1967 Saint Phalle and Tinguely created Paradis fantastique, a group of 15 moving figures, for the roof of the French pavilion at the 1967 Expo in Montreal. The following year, the premier of her piece ICH (All About Me) took place in Kassel; it was written in collaboration with Ranier von Diez, and Saint Phalle created the sets and costumes. During this era of protest, the Nanas became a powerful symbol: playful, buxom, free—they were everywhere. The artist created one of her first maisons nanas in the Midi region of France, as well as the beginnings of a nana town. In 1979, inspired by the 22 cards in the tarot deck, she began working on Le jardin des tarots (The Tarot Garden), a group of monumental works in cement, covered in glass and ceramic mosaics, on a piece of land in Tuscany. In order to finance this, her masterpiece, she worked on other minor pieces on the same theme. In 1973, she had created two versions of a script for the film Daddy, in which she starred, which explored her relationship with her father. Among her related projects were the Stravinsky Fountain outside the Pompidou Museum in Paris, in collaboration with Tinguely (1982), and Snake Tree, a fountain outside a children’s hospital on Long Island, New York (1988). In 1986, she wrote and illustrated a book of information about AIDS entitled AIDS: You Can’t Catch It Holding Hands: it was widely distributed and adapted into an animated film, which Saint Phalle directed with her son in 1989. After making an important donation to the musée d’art moderne et d’art contemporain de Nice in 2002, the artist succumbed to emphysema, caused by inhaling materials used for her famous Nanas.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

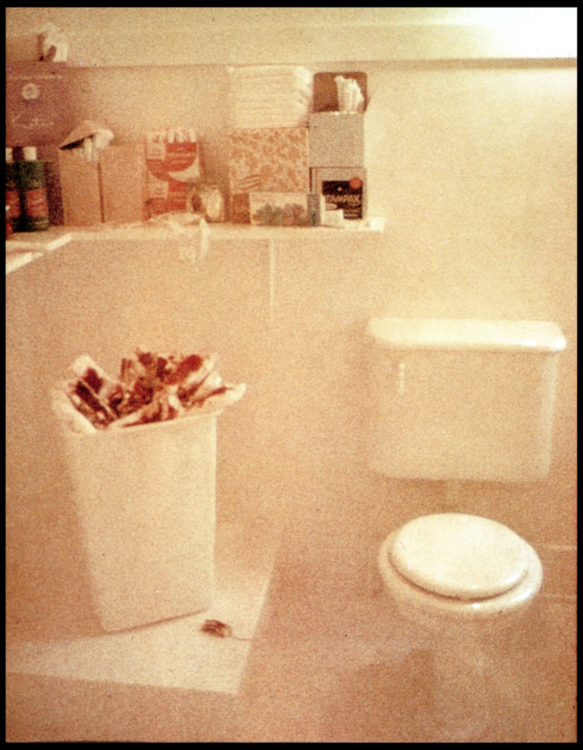

Niki de Saint Phalle, Tirs, 1961

Niki de Saint Phalle, Tirs, 1961  Tout un art - Niki de Saint Phalle | Waya Productions et les Abattoirs, Musée – Frac Occitanie Toulouse, 2022

Tout un art - Niki de Saint Phalle | Waya Productions et les Abattoirs, Musée – Frac Occitanie Toulouse, 2022