Research

Many artists in the 1960s took an interest in the dustbin as a sociological, critical and political object. The most striking example of this was probably Arman, who began researching the subject in 1959 by emptying out the contents of dustbins into transparent tanks1.

However, the artist was quickly faced with the problem of fermentation and smells, and so he began to sort through the refuse2, initiating a new series known today under the generic name Poubelles[Dustbins]. Although Arman considered sorting the garbage as an (appropriationist) “transgression of the gesture”3, it prevented the contents of his Poubelles from rotting as it usually does.

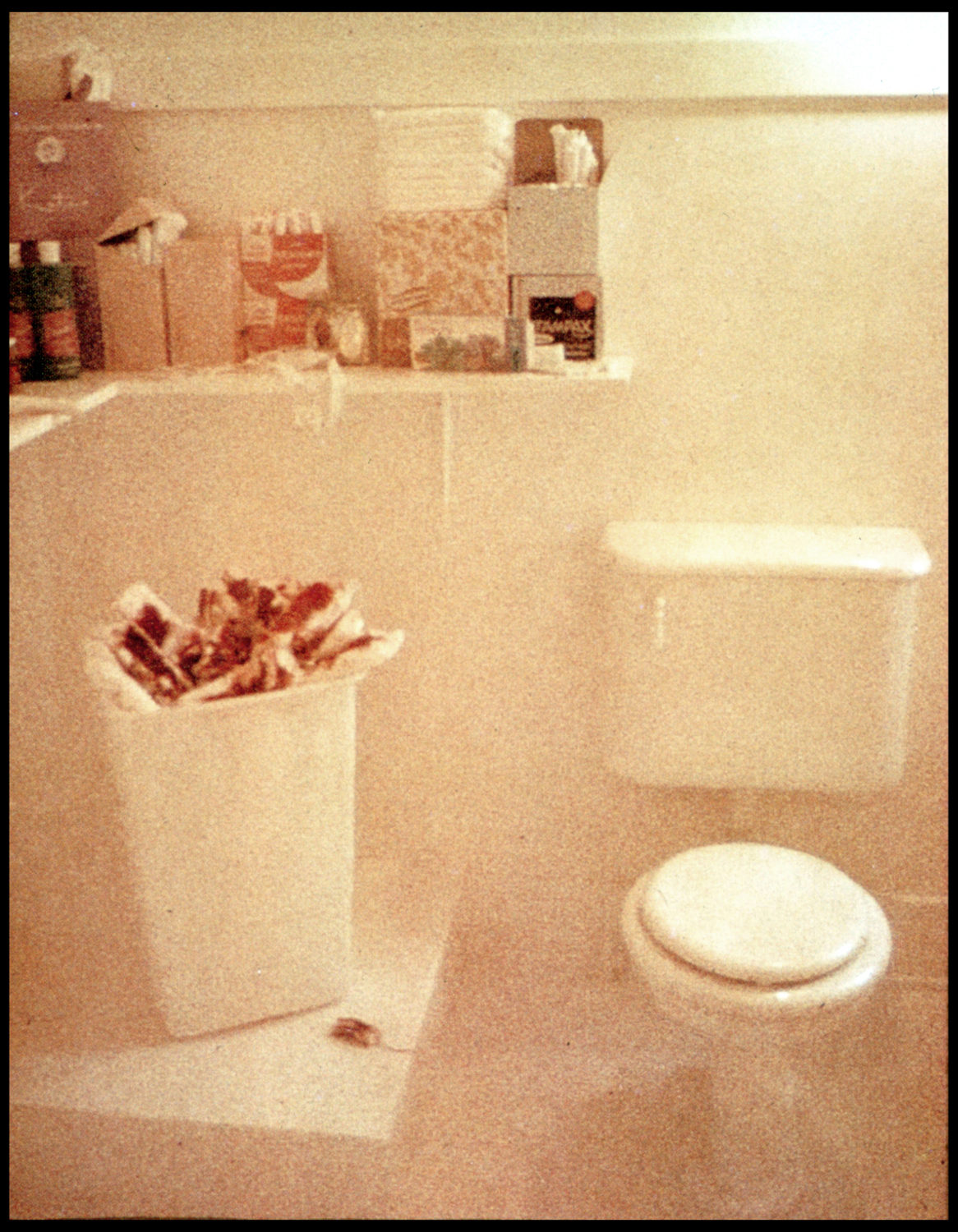

Arman, La Condition de la femme no 1, 1960, glass, wood, fabric, plastic, cork and metal, 92 x 46.2 x 32 cm, © Tate, 2017 / DACS, London / ADAGP, Paris

Niki de Saint Phalle, Assemblage, Blue Wood Ball, © Photo: André Morin, Courtesy Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois

Niki de Saint Phalle, Assemblage, Rusty Nail 2, © Photo: André Morin, Courtesy Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois

Niki de Saint Phalle, Assemblage, Strings 1, © Photo: André Morin, Courtesy Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois

In 1960 Arman created a piece with the ambiguous title La Condition de la femme no 1 [Condition of Woman I], which consisted in the contents of a bathroom bin. It would be unfair to accuse Arman of puritanism – for instance, La Condition de la femme n°1 contains a box of Tampax, as do two other Poubelles, Grands déchets bourgeois [Large Bourgeois Trash, 1960] and Poubelle de Jim Dine [Jim Dine’s Dustbin, 1961] –, but the fact that the “condition of woman” he evoked at the time remained expunged of the organic residues that bathroom bins usually contain is telling, to say the least. Despite the presence of a few tissues and cotton pads, the tampons in La Condition de la femme no 1 remain unused and wrapped4, thus making this specific image of the “condition of woman” in the early 1960s somewhat polite and perfectly acceptable. Arman’s contemporaries, who also took an interest in the dustbin, made even less allusions to gender, whether Daniel Spoerri’s La poubelle n’est pas d’Arman ! [The dustbin isn’t Arman’s!, 1961], Bernar Venet’s Performance dans les détritus [Performance in garbage, 1961]5, or Ben’s Les Poubelles vides [The empty dustbins, 1962]6: all of these works reference Arman’s, as tributes or criticisms. Only Niki de Saint Phalle seems to distance herself, with the small assemblages of non-organic waste drowned in plaster she made in the early 1960s. However, this little-known series was only shown posthumously and never studied in depth7. Furthermore, unlike Arman’s Poubelles, the domestic dimension of the litter is not affirmed: the plaster contains chalk sticks, paper clips, children’s toys, buttons, plastic flowers, screws, and all sorts of objects hardly related to bathroom or kitchen waste.

In his 1978 article “Poubelle’s blues”8, Gilbert Lascault evokes the many artists who took an interest in “leftovers”, in discards: Kurt Schwitters, Marcel Duchamp and Jean Dubuffet are mentioned alongside Arman, Daniel Spoerri, Piero Manzoni and Bernard Réquichot. And yet there is no mention of women in the art critic’s selection, although the subject of the dustbin as a receptacle for waste was often used by women artists, who made it into something very different from Arman’s Poubelles in function and implied meaning. One of the most famous of these pieces, a kind of doppelgänger of La Condition de la femme no 1, is probably Judy Chicago’s installation at the 1972 Womanhouse (Los Angeles)9. The installation, entitled Menstruation Bathroom, is a recreation of a bathroom, complete with immaculate walls and furniture, in which the bin – white, and placed on a pedestal like a classical statue – is overflowing with blood-soaked pads and tampons10. Whether the blood on the tampons and pads is real or painted red does not lessen the accusatory nature of the piece, which introduces, at least symbolically, soil and stink into the exhibition space – a line Arman dared not cross. The fact that the piece was presented in an independent rather than institutional context and was destined to be destroyed with the house around it six weeks later says a lot about the difference between Arman and Judy Chicago’s perceptions of artwork, the latter’s being characterised by a certain sense of urgency.

Two other artists from the Feminist Art Program Performance Group, Christine Rush and Sandra Orgel, performed various actions at the Womanhouse evocative of the condition of housewives – Ironing and Scrubbing. Although collecting rubbish was not included in these performances, it was nevertheless a subject of interest for feminist groups at the time, which strongly focused on women’s domestic chores. Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ “Manifesto for Maintenance Art” (1969), an ambiguous project that combined ecological reflections on the abundance of household waste and chores, is eloquent in this respect. The artist’s idea was to stay at the museum and maintain it: “The artwork would be (…) washing, feeding people, sweeping, dusting.11” Between 1973 and 1976, she carried out part of her manifesto’s projects in her Maintenance Art Performances12, during which she cleaned and dusted several museums. There was something awkward about the performance: as demonstrated by the artist in her Maintenance Art Manifesto, housekeeping – dishwashing, changing nappies, taking out the trash, etc. – still predominantly remains the underestimated work of women13.

In France and Belgium, these reflections were also particularly vigorous in the early 1970s: in 1974, Les Cahiers du GRIF devoted their second issue to the question of housework, entitled “Faire le ménage c’est travailler” (“Housekeeping is work”)14. While the review established no connection between these questions and contemporary art, one can easily imagine how these debates on women’s housework might well have encouraged the artists of the “Femmes en lutte” collective to present “heaps of garbage bags” [sic]15 at the 26th Salon de la Jeune Peinture in 1975. Aline Dallier retrospectively described the installation as a “denunciation of our domestic conditioning” – short sentences can be read on the bags, among which “Petite, occupe-toi de tes ordures!”16 [“Take out your own trash, girl!”]. The same year, Marianne Berenhaut presented her series of sculptures Poupées-poubelles (Dustbin-dolls) in the Cahiers du GRIF. While they do not include any waste per se, but rather debris – pieces of wool, leather, straw, iron fillings… – stuffed into stockings, their name is worth noticing. The artist explains the symbolic violence toward the female body in these words: “I can point violence out by using everyday objects […]; there is an addition of violence, and the world of dustbin-dolls, which is indeed a feminine world (not an asexual world), shows a certain violence – the female violence that I endure”17.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the dustbin was clearly associated with women’s domestic work. A French publication on the question confirms this assumption. Republished in 1963 and graced with the addition of a “Household art manifesto” likely to raise a smile after Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ “Manifesto for Maintenance Art”, the book L’art ménager and its thousand pages full of various household tips and tricks, devoted one of its chapters to “waste removal”18. In it, waste is hierarchised – a notion Arman would undoubtedly have found interesting –, sorted into combustible unperishable solids, perishables, and non-combustible unperishable solids, leading to various types of removal, among which the dustbin plays a crucial part. But no matter the variations in shape, material, colour, and openings, the conclusion is remains unchanged: it is the housewife’s duty to take out the bin full of “perishable and foul-smelling”19 waste.

The dustbin, as an object traditionally linked to the female world, was therefore a delicate subject for women artists to tackle in that they risked being considered representatives of a form of essentialist domestic art that would systematically revert them to their condition of women artists. By taking over the dustbin, men artists took away its highly political and gendered nature, consequently reducing it to silence as an instrument of domestic submission and turning it merely into the symbol of a general reflection on waste at a time when political ecology was on the rise. This article aims to restore the dustbin’s status as a fetish domestic object in the 1960s and 70s. It is also important to stress how the above-mentioned women artists, by using the dustbin in performative or short-lived contexts, far from museums or the market system, opposed the conception of a complete and exhibition-ready work of art as it was enounced in Arman’s Poubelles series.

Camille Paulhan (1986, France) is an art critic and historian who lives and works between Paris and Bayonne. She studied art history and in 2014 defended a thesis on the notion of the perishable in art in the 1960s-70s. She is a member of AICA France, publishes texts for exhibition catalogues and specialised magazines, and is also a correspondent for the Lyon-based review Hippocampe. She teaches art history at the École d’art de Bayonne and École supérieure d’art des Rocailles in Biarritz.

About these pieces, see Renaud Bouchet, La première série des Poubelles (1959-1966) dans l’œuvre d’Arman (né en 1928) (sup. Jean-Paul Bouillon), Master’s dissertation in art history, Université Blaise-Pascal – Clermont II, 2002, p. 22. Almost no photographic trace remains of these first Poubelles.

2

See Renaud Bouchet, “Dialogue épistolaire avec Pierre Restany autour des Poubelles d’Arman (mai 2001 – décembre 2002)”, Cahiers du musée national d’Art moderne, no. 96, Summer 2006, p. 89.

3

Arman, interview with Catherine Millet, art press, no. 8, December 1973 – January 1974, p. 16.

4

The author thanks Katie Dungate, conservation administrator at Tate Modern, for the specifications about this Poubelle [email to the author, 2 December 2013].

5

About this piece, see Damien Sausset, “Les ‘performances’ de Bernar Venet dans une problématique du contexte”, Bernar Venet: performances, etc. 1961-2006, Milan, Charta, 2006, p. 71.

6

About this piece, see Ben: strip-tease intégral, exh. cat. (Musée d’art contemporain de Lyon, 3 March – 11 July 2010), Paris, Somogy, 2010, p. 84.

7

In 2013, the Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois Gallery published the catalogue “En joue! Assemblages & Tirs (1958-1964)” on the occasion of the exhibition of the same title, Paris/Hanover, Galerie Vallois/Ahlers pro arte Foundation.

8

Gilbert Lascault, “Poubelle’s blues”, Traverses, no. 11, May 1978.

9

About the Womanhouse, see: Miriam Shapiro, “The Education of Women as Artists: Project Womanhouse”, Art Journal, vol. 31, no. 3, Spring 1972; Judy Chicago, Through the Flower: My Struggle as a Woman Artist, New York, Anchor Books, 1977; Arlene Raven, “Womanhouse”, Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard, The Power of Feminist Art, New York, Harry N. Abrams, 1994. See also Joanna Demetrakas’ documentary Womanhouse, 1974, rereleased in 2013 by Le peuple qui manque.

10

The effective presence of real menstrual blood in Menstruation Bathroom remains unclear, despite the photographs of the piece showing a white bin overflowing with bright red used tampons and sanitary pads. The room Chicago mentioned was “very, very white and clean and deodorized – deodorized except for the blood, the only thing that cannot be covered up”; Arlene Raven, on the other hand, speaks of “(fake) bloody tampons and kotex”. See Judy Chicago, quoted by Arlene Raven, “Womanhouse”, op. cit. p. 57, and Arlene Raven, Crossing Over: Feminism and Art of Social Concern, London, EMI Research Press, 1988, p. 119.

11

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, interview with Bénédicte Ramade, in Écoplasties: art et environnement (eds Nathalie Blanc and Julie Ramos), Paris, Manuella, 2010, p. 268.

12

About these works and the question of domestic art, see Helen Molesworth, “House Work and Art Work”, in Art After Conceptual Art (eds Alexander Alberro and Sabeth Buchmann), Cambridge/London, MIT Press, 2006, pp. 72 and following.

13

To read the full “Manifesto for Maintenance Art”, see Documents, no. 10, Autumn 1997, pp. 6-7.

14

Les Cahiers du GRIF, no. 2, 1974.

15

Francis Parent and Raymond Perrot, Le Salon de la Jeune Peinture: Une histoire (1950-1983), Paris, Jeune Peinture, 1983, p. 164.

16

Aline Dallier, “Le mouvement des femmes dans l’art”, Opus International, no. 66-67, Spring 1978, p. 37.

17

Marianne Berenhaut, “Poupées-poubelles”, Cahiers du GRIF, no. 7, June 1975, p. 48. About Marianne Berenhaut’s Poupées-poubelles from the early 1970s, see Isabelle de Longrée, “Poupées et tabous, le double jeu de l’artiste contemporain”, Poupées et tabous: le double jeu de l’artiste contemporain, exh. cat. (Maison de la Culture, Namur, 19 March – 26 June 2016), Paris, Somogy, 2016, pp. 74-75.

18

Paul Breton (ed.), L’Art ménager, Paris, Flammarion, 1963 [1952], pp. 931 and following.

19

Ibid.

Camille Paulhan, "« Take out your own trash, girl! »." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/take-out-your-own-trash-girl/. Accessed 18 July 2025