Rachel Whiteread

Chillida Alicia (ed.), Rachel Whiteread, exh. cat., Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid (11 February–22 April 1997), Madrid, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 1997

→James Lawrence, Rachel Whiteread, Gagosian Gallery, 2008

→Allegra Pesenti (ed.), Rachel Whiteread Drawings, exh. cat., Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (31 January–25 April 2010), Los Angeles, Hammer Museum and DelMonico Books, 2010

Rachel Whiteread, Tate Britain, London, 12 September 2017–21 January 2018

→Rachel Whiteread, Transient Spaces, Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin, October 27–January 13 2002

→Rachel Whiteread, British Pavilion, 47th Biennale di Venezia, Venice, 15 June–9 November 1997

British sculptress.

Exploring themes of absence and the memory of place by playing with sensory perceptions of space, Rachel Whiteread pursues a systematic process which certain critics have likened to minimalist or conceptual art. Following the example of architect Luigi Moretti’s 1950s-era plaster models of interior spaces, she has refined her process: create volume using empty space, conferring a materiality to the invisible. She studied at Brighton Polytechnic, then trained in sculpture at the Slade School of Fine Art, University College of London (1985-1987). Her first exhibit took place at the Carlisle Gallery in London in 1988. There, she showed Closet, the reproduction of the interior of a clothes closet, in the form of a plaster structure covered in wood and felt. She had already begun to apply the practice of mold-making to her own body, of which she made several impressions that she was not bold enough to show.

In 1992-1993, she took part in a university exchange with Germany, and traveled to Berlin to refine her project of casting familiar, banal shapes, of which she attempted to show a hidden face, and reveal unknown usages: sinks, bathtubs, mattresses, the undersides of tables, the interiors of kettles, bookcases, and even an autopsy table. These molds were made in plaster and various other materials, including resin, rubber, and plastic, in a monochrome palette which often glimmered, like gemstones. She hoped to pay homage to “life’s underbelly,” and to the nostalgic qualities of the objects that surround us every day. Her work became more impersonal, less autobiographical. She won the 1993 Turner Prize for House at the age of 30, making her the first female artist to receive this prestigious award. House (1993-1994) was a concrete cast of the interior of an entire Victorian house in the East End of London, which she couldn’t prevent from being demolished — the last of a group of abandoned homes, destined to disappear. Emptiness transformed into fullness, the most intimate into the monumental. The house was no longer a construction, an addition, but rather a subtraction. It appeared then as a mausoleum, as a death mask or a memorial, that fixed a negative space — for its doors couldn’t open, its windows were obstructed: the house became an impenetrable surface, which confronted the viewer with its mute resistance.

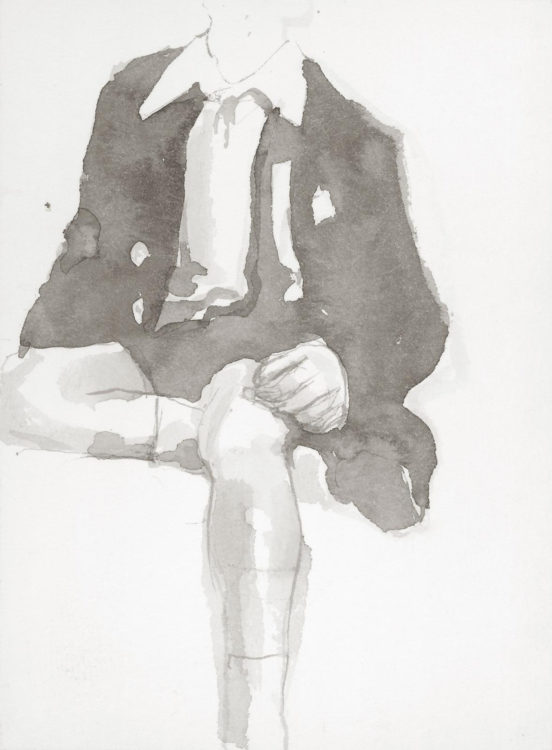

After her representation at the British Pavilion at the 1997 Venice Biennale (the first woman to represent Britain alone), she received various public commissions such as Water Tower (New York, 1998) and Holocaust Memorial (Vienna, 2000). Her work is part of several public collections. Her first show at the Nelson-Freeman Gallery in Paris (2010), brought together, in the form of still lifes, a collection of sculptures in resin and tinted plaster, casts of quotidian objects like cardboard tubes, medicine bottles, bits of packaging, all combined into an abstract landscape in pastel tones. Whiteread’s works on paper, although infrequently exhibited, occupy a central place in her creative process.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Rachel Whiteread, Tate Britain

Rachel Whiteread, Tate Britain