Raymonde Arcier

Dumont Fabienne, « Implication féministe et processus créatif dans les années 1970 en France : les œuvres de Raymonde Arcier et Nil Yalter » in Camus Marianne, Dupont Valérie (ed.), Création au féminin., vol. 2, Dijon, Éditions universitaires, 2006

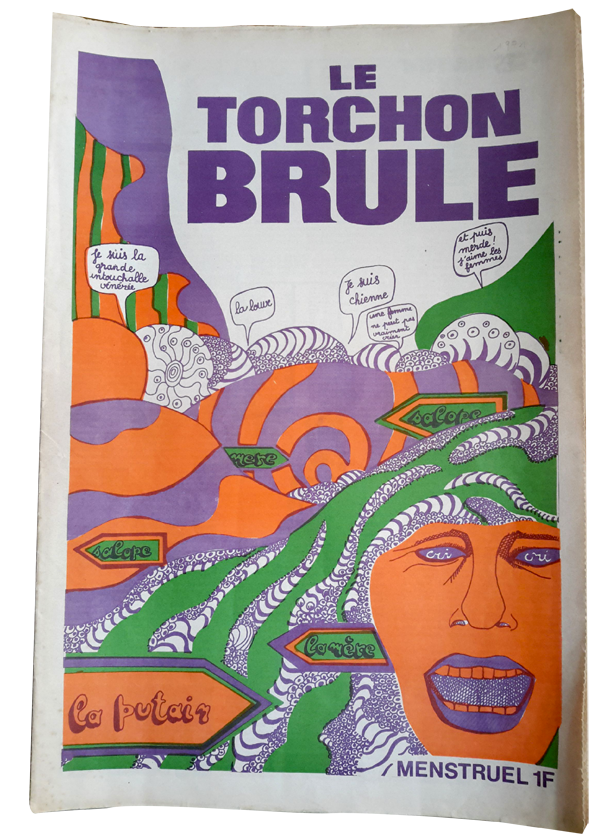

→Dedieu Marie, Le torchon brûle, no. 0, December 1970; 6 issues from May 1971 to June 1973; reprint, Paris, Éditions des femmes, 1982

→Arcier Raymonde, L’héritage, Paris, Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, 1978

Contre-cultures (1969-1989). L’esprit français, La Maison Rouge, Paris, 24 February–21 May 2017

French visual artist.

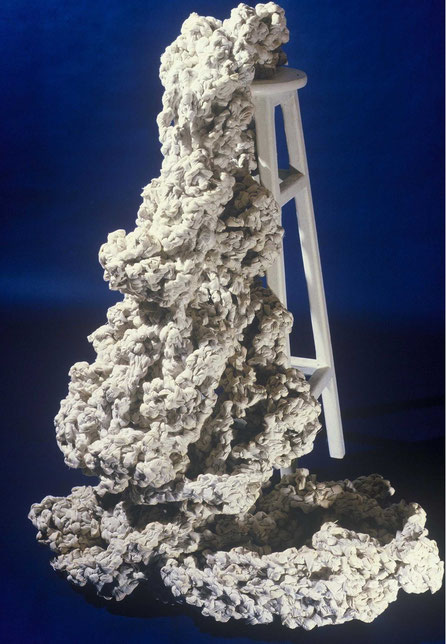

Active within the feminist movement from its earliest days, Raymonde Arcier, an office worker and self-taught artist, resumed her sociological studies at Vincennes University and, from 1970 on, produced her most striking works, crocheting wool and cotton, and knitting metal—with each piece demanding up to a year’s work. Through her appropriation of this female cultural apprenticeship, she wittily conjured up her social confinement, trying—to use her own words—to “make everyone aware of the huge labour of women”; as for housewives’ bags, she tried to “illustrate the time, energy, money, fatigue and pleasure involved in filling them, and emptying them; emptying them, and filling them”.

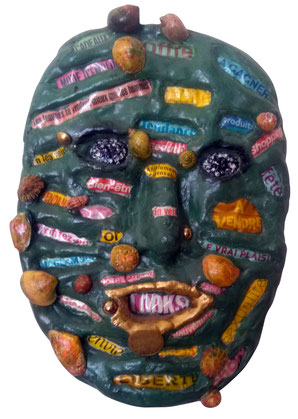

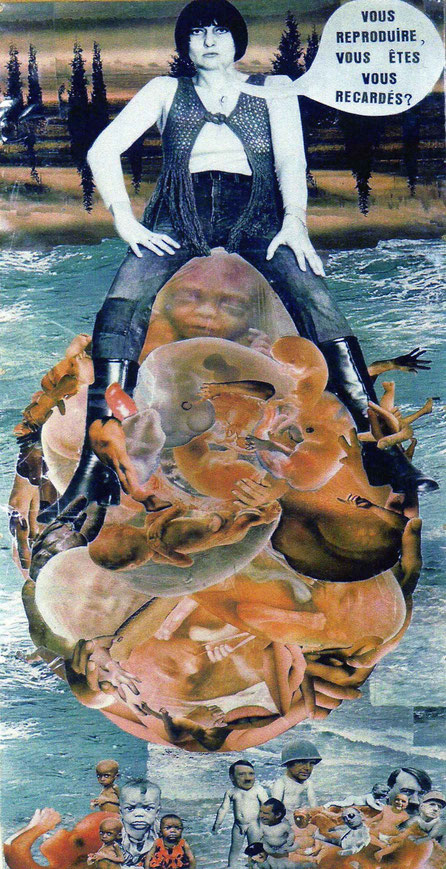

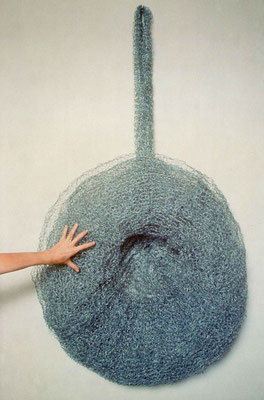

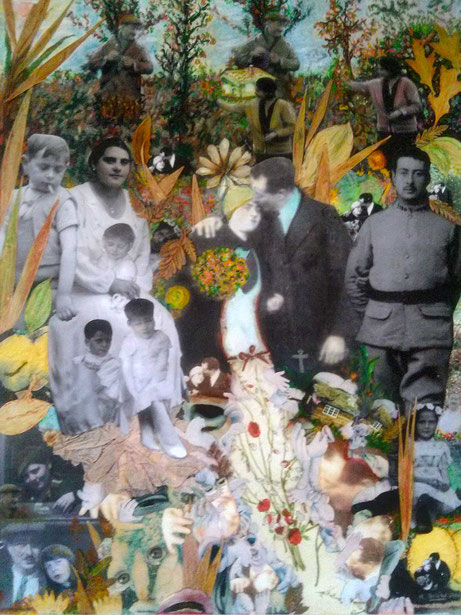

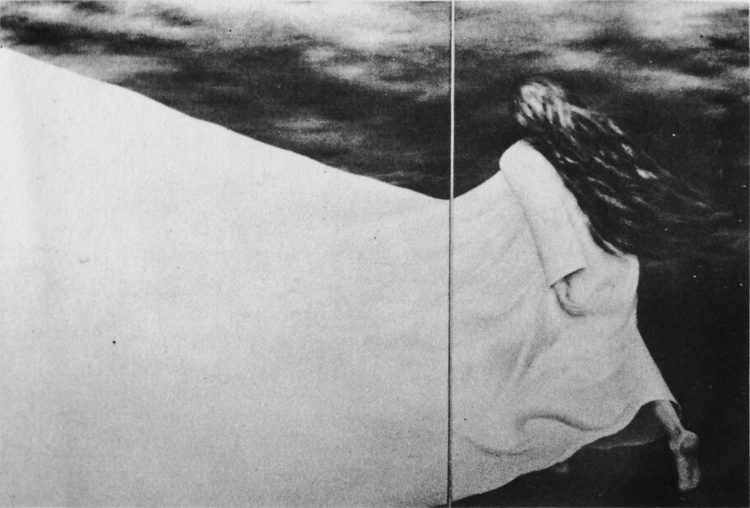

Among her monumental sculptures we find Faire ses provisions (1971), huge shopping bags, awkward to carry, made of nylon string knitted with garter stitching, Héritage (Les Tricots de ma mère, 1972-1973), a huge unwearable sweater made with crocheted wool lined with hessian, Paille de fer pour ca(sse)role, 1974-1975, and a scouring sponge, one meter [40 inches] in diameter, weighing seven kilos [16lbs]. In order to free herself from them, to gain recognition for them, and share them, she treats household chores in the mode of the gigantic, the off-beat, and the excessive, on a par with the oppression suffered, as in Au nom du père (1975-1976), which made the front page of La Revue d’en face, in March 1979: a very large woman filled the exhibition space, standing stoutly on both legs, with her arms outstretched cross-like, crucified on household and sexual tasks. In the same vein, she produced Mère et petite mère (1970) and Jeu de dame (1971), a tapestry consisting of the square arrangement of eight dirty floor cloths and eight clean floor cloths, turned into an abstract artwork, resulting from that much decried daily round. While carrying on her professional activities, Raymonde Arcier then became involved in writing and diverse visual works, in particular paintings and collages.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Meeting with Raymonde Arcier, Cathy Bernheim and Geneviève Fraisse, La Maison Rouge, Paris

Meeting with Raymonde Arcier, Cathy Bernheim and Geneviève Fraisse, La Maison Rouge, Paris