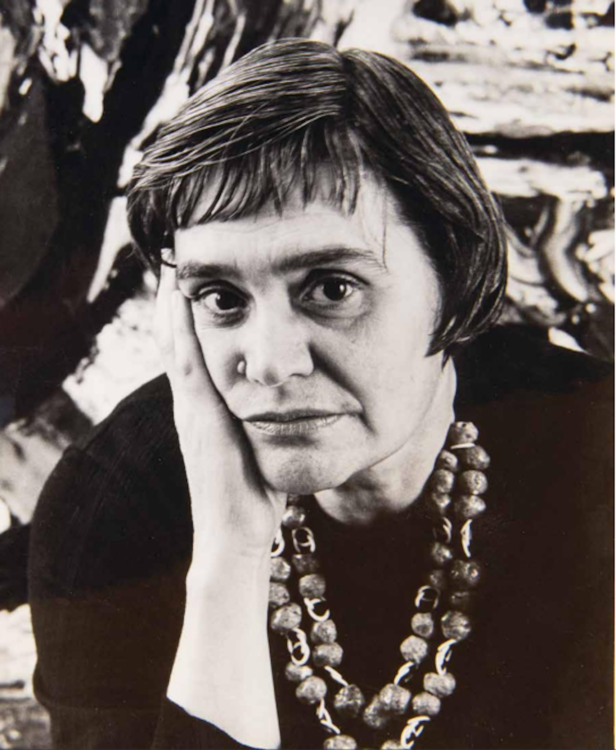

Sonia Delaunay

McQuaid, Matilda, Brown, Susan, Color Moves: Art and Fashion by Sonia Delaunay, New York, Smithsonian Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, 2011.

→Baron, Stanley, Dolski, Robert (trad.), Sonia Delaunay : sa vie, son œuvre (1885-1979), Paris, J. Damasse, 1995

→Damasse, Jacques, Sonia Delaunay : rythmes et couleurs, Paris, Hermann, 1971

Sonia Delaunay, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, February 12 – June 12, 2022

→Sonia Delaunay, Tate Modern, Londres, April 15 – August 9, 2015

→Sonia Delaunay, Gimpel & Hanover Galerie, Zurich, October 1965, Gimpel Fils Gallery, Londres, February 1966

Painter, textile artist and decorator Russian.

Sarah Stern, known to history as Sonia Delaunay, spent her early childhood in Ukraine. At the age of five she was taken in by her maternal uncle Henri Terk, adopted the name Sonia Terk, and went to live in St. Petersburg. She began studying art in Karlsruhe, Germany, in 1903 and moved in 1905 to Paris, where she studied French Post-Impressionism and Fauvism without breaking with the memory of the brightly-coloured icons of the Slavic tradition. She then made a series of expressionist portraits with strong colour ranges (Philomène, 1907).

After a brief marriage, for administrative convenience, to the German gallerist Wilhelm Uhde, she divorced and married Robert Delaunay in 1910. The union would lead to the birth of their son Charles in 1911.

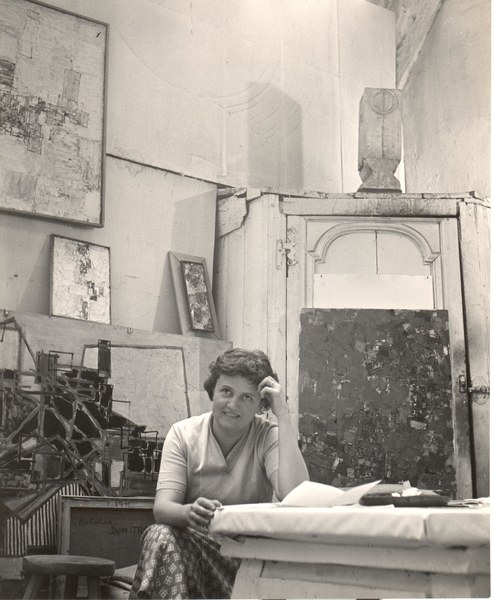

Moving among the originators of abstraction, the couple created what Guillaume Apollinaire called “Orphism” and what Delaunay more often described as “simultanism” or “simultaneism”: art whose constructive and dynamic power is based on colour rather than on form or subject. S. Delaunay, meanwhile, aimed to create a synthesis between painting and what was not yet referred to as “design” but rather as “applied arts”. As such, at the same time as she produced paintings such as Electric Prisms (1914), she also made her first clothes and objects, which she called “simultaneous dresses”. From 1914 to 1921, the Delaunays lived in Portugal and Spain. She painted still lifes and colourful landscapes, and continued to experiment with fabrics, scarves, pottery, and objects she bought at local markets. The October Revolution (1917), which the couple welcomed with joy, ended the family’s stream of income from St. Petersburg. After creating set designs and costumes for the Russian Ballet (Cleopatra, London, 1918), she opened the Casa Sonia (1918-1921) in Madrid, a shop of accessories for fashion and interior decoration, which became a success.

Returning to Paris in 1921, she began to showcase her products (clothing, among other things) through Dadaist shows and Russian balls. In 1924, she opened a textile workshop, Simultané, and then La Maison Sonia (1925-1931). At the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in 1925, she presented her pieces in the Simultané boutique – luxurious confections that were acclaimed by the international press. During the same year, she considered the issue of the democratization of fashion with the invention of the “master fabric” – a fabric already cut into the shape of clothing.

Alongside these creations, which have as much to do with the vocabulary of Russian constructivism as they do with the ornamental richness of Art Deco, the world of abstract art informed the way these items were presented in window displays and her painted Groupes de femmes [Groups of women]. Economic crisis led to the closing of the Simultanéboutique in 1930, but the workshop remained in operation until 1934. The artist then adopted a strict, purely abstract language, one characteristic of the concrete art movement of the 1930s. For the couple, the means of expressing themselves creatively were as important as the formal imperative of abstraction. With his project for a phalanstery of artists in Nesles-la-Vallée, R. Delaunay proclaimed the beginning of the “Modern Age” and a return to craftsmanship. Committed to the cause of muralist art, the Delaunays participated in large collective projects.

With others, including the architect and decorator Félix Aublet, they founded the Art et Lumière association, which decorated the Air and Railways Pavilions for the 1937 International Exhibition of Art and Technology – these decorations earned them a gold medal.

After the death of her husband in 1941, S. Delaunay fought for his work to be recognized. She also continued to create both everyday objects and projects meant to be integrated into architectural design. She adhered to various factions within abstract art and participated in exhibitions at the Denise René gallery when geometric abstraction witnessed a revival during the Op Art movement. In collaboration with the Artcurial gallery, she published lithographs and articles based on her research during the inter-war period, a piece of artistic output that continues to feed into the debate about the reproducibility of works of art. With her son Charles, she made several major donations. She created her last gouache a few weeks before her death. A year later, a traveling retrospective in the United States paid tribute to her work.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2022

Femmes artistes : Sonia Delaunay – Musée d’arts de Nantes, 2021

Femmes artistes : Sonia Delaunay – Musée d’arts de Nantes, 2021  Sonia Delaunay | Pionniers, Pionnières | Centre Pompidou, 2021

Sonia Delaunay | Pionniers, Pionnières | Centre Pompidou, 2021

![<i>La Houle</i> [The Swell]: First Research on the Place of Women Artists in the Collections of the Centre National des Arts Plastiques - AWARE](https://awarewomenartists.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/barbara-kruger_who-do-you-think-you-are_1997_aware_women-artists_artistes-femmes-750x532.jpg)