Tarsila do Amaral

Amaral Aracy, Tarsila : sua obra e seu tempo, São Paulo, Editora Perspectiva, Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 1975

→Amaral Aracy, Tarsila do Amaral, Buenos Aires, Banco Velox, 1998

→Gotlib Nadia Battella, Tarsila do Amaral : a modernista, São Paulo, Editora Senac São Paulo, 2003

Tarsila do Amaral : mito e realidade no modernismo brasileiro, Museu de arte moderna, Sao Paulo, 25 October – 15 December 2002

→Tarsila do Amaral, Fondacion Juan March, Madrid, 6 February – 3 March 2009

→Tarsila do Amaral : inventing modern art in Brazil, The Art institute of Chicago, Chicago, 8 October 2017 – 7 January 2018 ; The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 11 February – 3 June 2018

Brazilian painter.

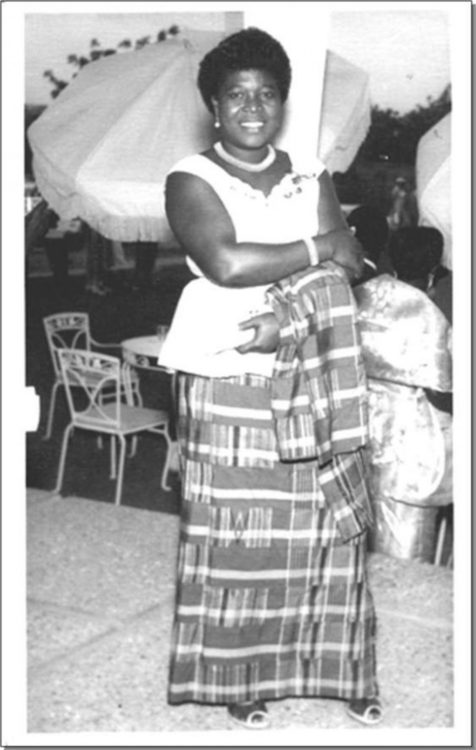

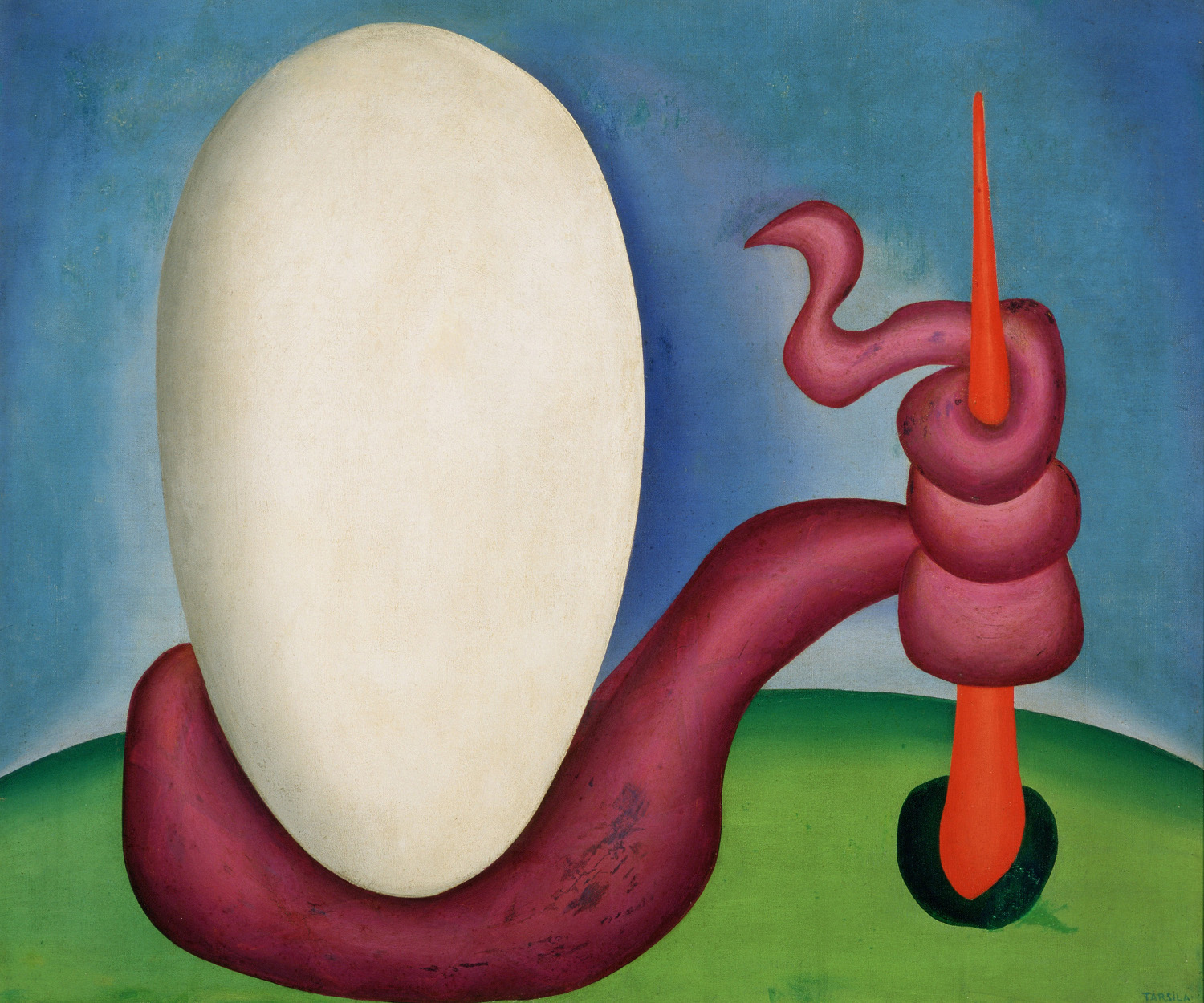

Tarsila do Amaral was born to a family of wealthy coffee producers and spent her childhood in her parents’ haciendas and travelling with them throughout Europe. By the age of 30, she had married one of her cousins and had a daughter, and started taking private lessons from Pedro Alexandrino Borges, then a leading figure of academic painting in São Paulo. She moved to Paris in 1920 and enrolled in the Académie Julian. Despite the academy’s traditional teachings, she found inspiration in the city’s more avant-garde circles. While she was away, São Paulo hosted one of the founding events of Brazilian modernism: the Semana de arte moderna in 1922. She quickly moved back to her home country, where she joined the São Paulo-based Grupo dos Cinco (Group of Five) – T. do Amaral, Anita Malfatti, Oswald and Mário de Andrade, and Menotti del Picchia –, which would go on to become a cornerstone of the future modernist movement. In 1923, she was invited to the Salon des artistes français and became acquainted with Blaise Cendrars, Jean Cocteau, Robert Delaunay, Constantin Brancusi and Fernand Léger during her stay. In the early 1920s, the theme of São Paulo transforming under the influence of rapid metropolitanisation became a leitmotiv in her work, which she treated in a figurative style tinged with dream-like and playful overtones, with rigorous compositions based on the use of sharp lines and a Fauvist palette. In 1924, a trip to the Brazilian province of Minas Gerais broadened the perspective of the elitist urbanites to the existence of the country’s heartland. Inspired by the popular subjects she encountered there, T. do Amaral painted a series that she named after the tree that gave the country its name, the pau-brasil (brazilwood). This was also the term that Oswald de Andrade, the painter’s new partner, chose to name the first modernist manifesto, the Pau-Brasil Manifesto (1924), in which he declared that an autonomous Brazilian art form would only be achievable through the harmonious integration of Native American, African, and European influences. In January 1928, T. do Amaral offered him her painting Abaporu (“man-eater” in the Tupi-Guarani language), depicting a microcephalic and melancholy giant with enormous feet sitting in a minimalistic landscape with blue skies, a yellow sun, and a green plain with cacti.

That same year, the Manifesto antropófago (“anthropophagite manifesto”), written by O. de Andrade in echo to her picture, acknowledged the first manifesto’s shortcomings and called for the adoption of primitivism as a critical weapon for cultural selection. This acknowledgement of the underlying violence of intercultural relations produced a shift in the æsthetic subject of Brazilian modernism, whose preoccupations at the time focused predominantly on socio-political issues, which do Amaral shared and which were bolstered in 1931, when she travelled to Moscow for her exhibition at the Museum of Occidental Art. Upon returning to Brazil, she took part in the revolt against dictator Getúlio Vargas in 1932. Considered a communist sympathiser, she was imprisoned with her new partner Osório Cesar. Her stay in the Soviet Union, where the poverty of the population left a deep impression on her, would inspire her painting (Segunda class [Second Class], 1933; Operários [Workers], 1933). From then on, her work suffered a formal regression as the expressive realism of the 1930s and ’40s replaced the accomplished innovations of the previous decade. In 1936, she started working as a columnist for the weekly magazine Diário de São Paulo, which was owned by her friend, the powerful press mogul Francisco Assis Chateaubriand. In the 1950s, she gave up socialist-inspired painting and reverted to the themes of her Pau-Brasil period. She painted up until her death and in her later days received a number of tributes of recognition for her contribution to the revival of Latin-American art in the 1920s. Her work was exhibited, among others, at the first São Paulo Biennale in 1951, and she represented her country at the 1964 Venice Biennale. A major retrospective of her work, Tarsila, 50 Years of Painting, was held in 1969 at the Museum of Contemporary Art of São Paulo University and at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2018

Tarsila do Amaral: Inventing Modern Art in Brazil

Tarsila do Amaral: Inventing Modern Art in Brazil

![<i>La Houle</i> [The Swell]: First Research on the Place of Women Artists in the Collections of the Centre National des Arts Plastiques - AWARE](https://awarewomenartists.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/barbara-kruger_who-do-you-think-you-are_1997_aware_women-artists_artistes-femmes-750x532.jpg)