Gashū Ogura Yuki (A collection of works by Yuki Ogura). Edited by Natsuko Kusanagi. Tokyo: Nihon Keizai Shinbunsha, 1993.

→Ogura, Yuki. “Tōtō ekaki ni natte shimatta (In the end, I became a painter).” In Ogura Yuki gashū: Gagyō shichijūnen. Tokyo: Asahi Shinbunsha, 1986.

→Ogura, Yuki. Gashitsu no uchisoto (The art studio inside and out). Tokyo: Yomiuri Shinbunsha, 1984.

Yuki Ogura, Hiratsuka Museum of Art, October–November 2018

→Yuki Ogura: Ten Years After Her Death, Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art, Kobe, February–April 2010; Utsunomiya Museum of Art, April–May 2010

→Yuki Ogura, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, August–October 2002; The Museum of Modern Art, Shiga, October–November 2002

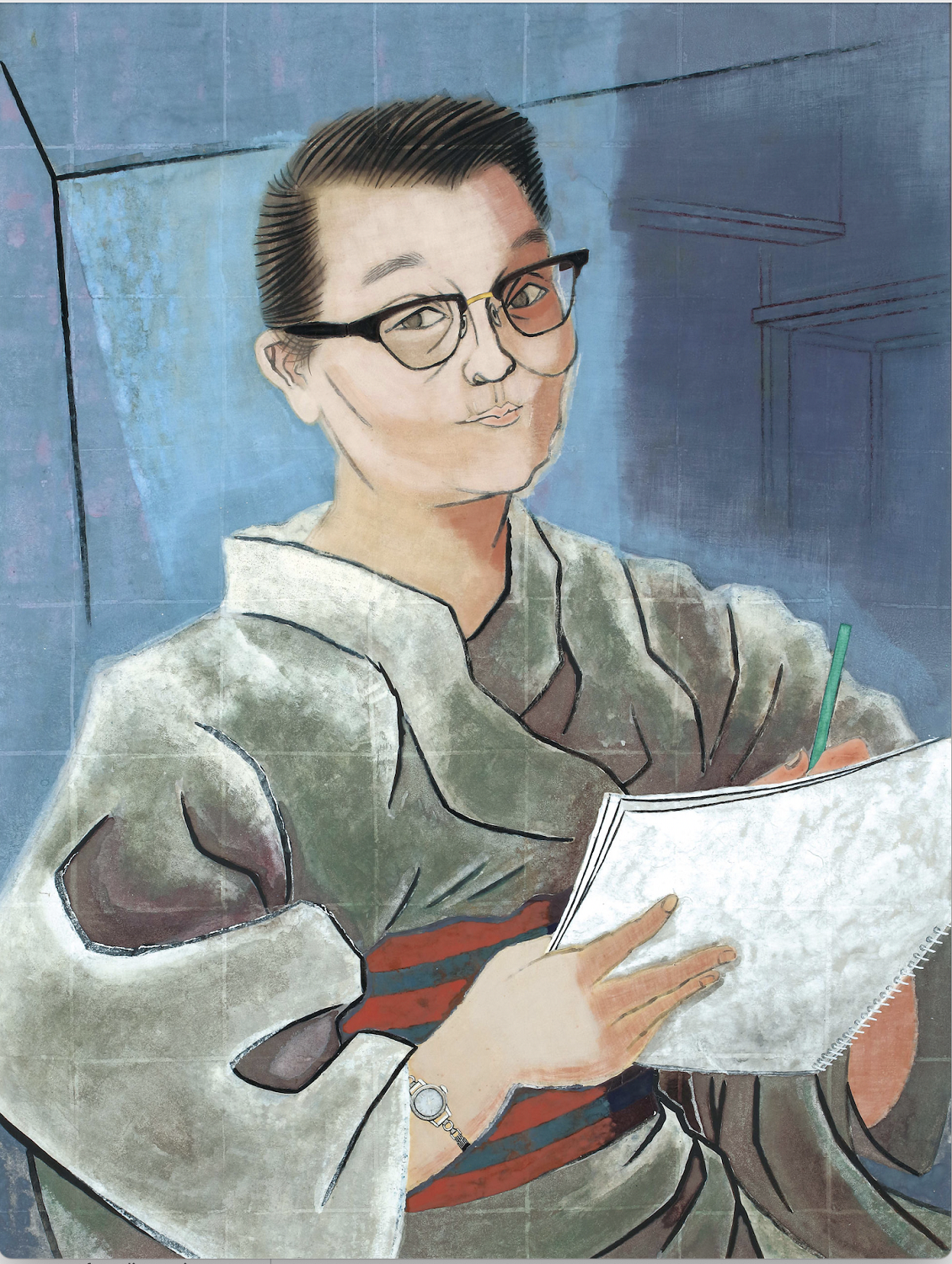

Japanese Nihonga painter.

Yuki Ogura was a Japanese Nihonga (Japanese-style) painter, who remained active until her death in 2000 at the age of 105. Though many of her female contemporaries abandoned their painting activities due to the difficulties of striking a balance with family life, Yuki Ogura was that rare individual who was able to establish a solid reputation and position within the Japanese art world, as demonstrated by the fact that in 1980 she became only the second woman painter to receive the Bunka Kunshō [Order of Culture].

Yuki Ogura graduated from the Nara Women’s Higher Normal School (now Nara Women’s University) with honours in 1917 and subsequently established herself as a teacher. She had only taken painting classes while enrolled at the university, but following a period of self-study, she began an apprenticeship with the Nihonga painter Yasuda Yukihiko (1884–1978). After that, she sought admittance to the public exhibition of the Nihon Bijutsuin [Japan Art Institute], of which Yasuda was a member, and was selected to participate for the first time in 1926 at the age of 31. In 1932, she became the first woman to be elected to serve as a member of that organisation.

The Japan Art Institute is an unaffiliated art organisation founded in 1898 as a type of graduate school for the study of Nihonga and sculpture. Its revival in 1914 was accompanied by a declaration of respect for East Asian art traditions and its members’ freedom of expression, fostering the talents of many young artists. During her time with the organisation, Yuki Ogura struggled to balance the pressures of membership with her work as a teacher while caring for her sick mother, but credited Zen practice with the cultivation of her personal growth. In 1938 she married the Zen master Tetsuju Ogura, who was thirty years her senior, expending considerable effort to continue her work while caring for both her mother and her husband.

The words of her mentor, Yasuda Yukihiko, who told her not to lose sight of the reality of her subjects, nor to restrict herself to the styles she had previously developed, served as the guiding principle by which Yuki Ogura pursued her career. With these teachings in mind, she turned to those objects that were close to hand, seeking to create works that capture the life within the subject and their central points of interest.

A representative example of her early work is Yoku on’na sonoichi [Bathing Women, 1938], which depicts the fluctuations of water through the bold distortion of the submerged figures and lines of the tiles. This painting, which avoids the sentimentality typical of bathing pictures, instead searches for the intricacies of form, a clear indication of Yuki Ogura’s interest in modelling techniques. In a subsequent painting, Yoku on’na sono ni [After Bathing, 1939], the diverse gestures of a group of women in a bathing house changing room are contrasted with the symmetrical pattern of the flooring to produce an unusual visual effect.

In the wake of Japan’s defeat in 1945, Western art began to be introduced to Japan in the 1950s, and Yuki Ogura learned modelling techniques from these pieces that she then incorporated into her own Nihonga works. In Kō-chan no kyūjitsu[Miss KOSHIJI Fubuki’s day off, 1960], with its vivid red background and melange of upholstery frabric and kimono fabric patterns, we find similarities to the works of Henri Matisse, while the heavy, distorted bodies of Mother and Child(1961) recall Pablo Picasso. During this period, Yuki Ogura’s style did not stop at mere imitation, but fused European techniques with the decorative qualities of traditional Nihonga, and she began amassing awards for her work.

At the age of 70, Yuki Ogura’s style changed once again. Although the composition these works is more elaborated, the rendering is clearer and more concise, depicting (in the artist’s own words) “bright, warm and pleasant things” that have resonated with many people. Wataru [On a path, 1966], which shows a mother, child and dog on a walk, remains a popular work that softens the hearts of men and women of all ages to this day. This work was conceived with the idea of the single-minded devotion of a monk to the Buddha in mind, and expressing such an idea in this way constitutes the core of Yuki Ogura’s mature period. Furthermore, the charm of the still lifess that she continually produced until her later years is unforgettable. Her mentor, Y. Yasuda called them “Kita-Kamakura Specialities”, after her residence in Kita-Kamakura.

Yuki Ogura became a member of the Japan Art Academy (Nihon Geijutsuin) in 1976 and served as the board chairman of the Japan Art Institute, in which she had long been active, from 1990 to 1996. Her publications include Gashitsu no naka kara [From the art studio, 1979] and Gashitsu no uchisoto [The art studio inside and out, 1984].

A biography produced as part of the “Women Artists in Japan: 19th – 21st century” programme

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2023