Fujio Yoshida

Allen Laura W., A Japanese legacy : four generations of Yoshida family artists, Minneapolis, Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 2002

→Yamamura, Yoshida Fujio: A painter of Radiance, Fuchu Art Museum, 2002

The Yoshida Family – An Artistic Legacy in Prints, Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, South Hadley, 20 January 2015 – 14 June 2015

Japanese watercolourist, painter and engraver.

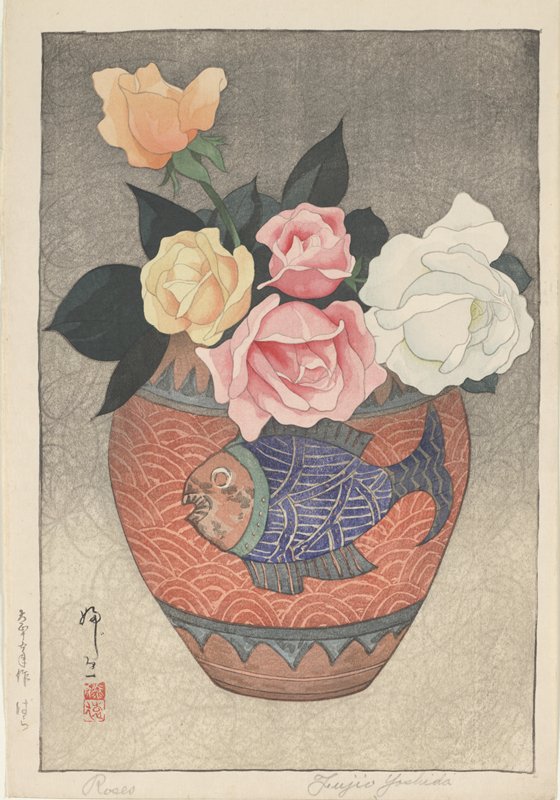

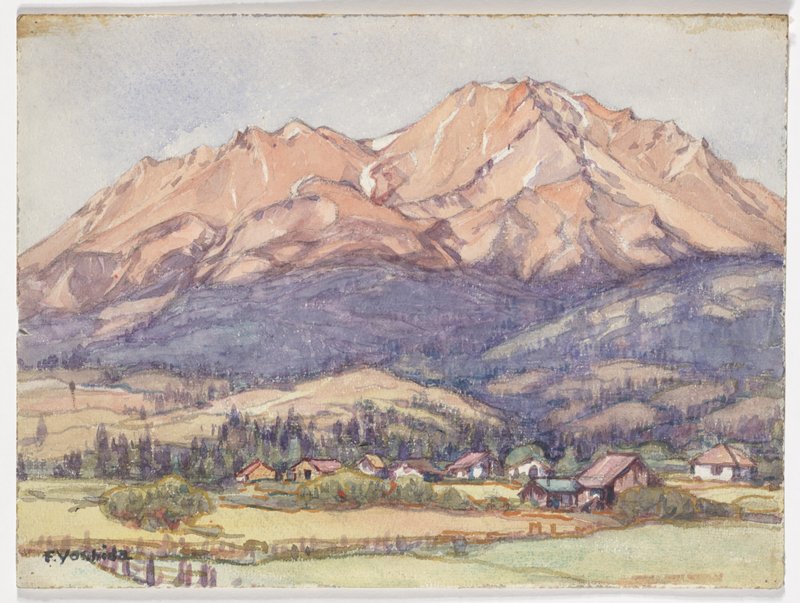

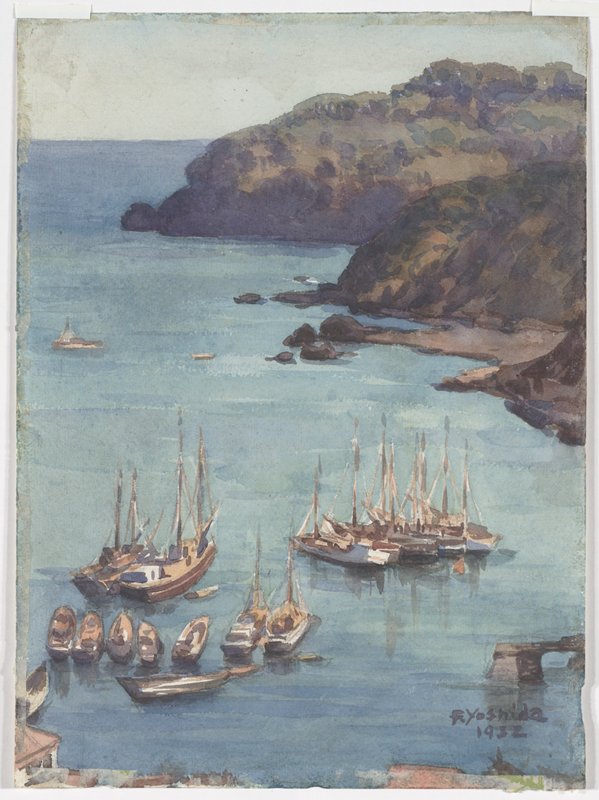

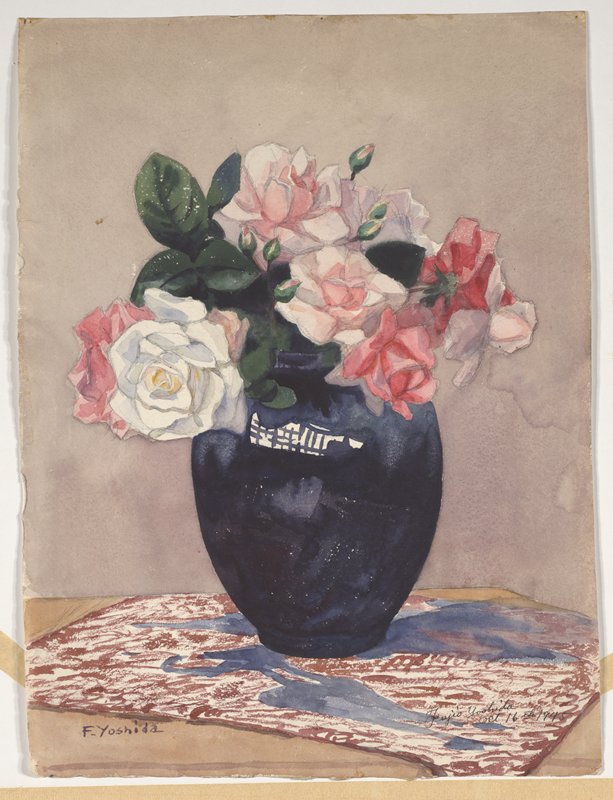

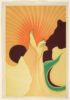

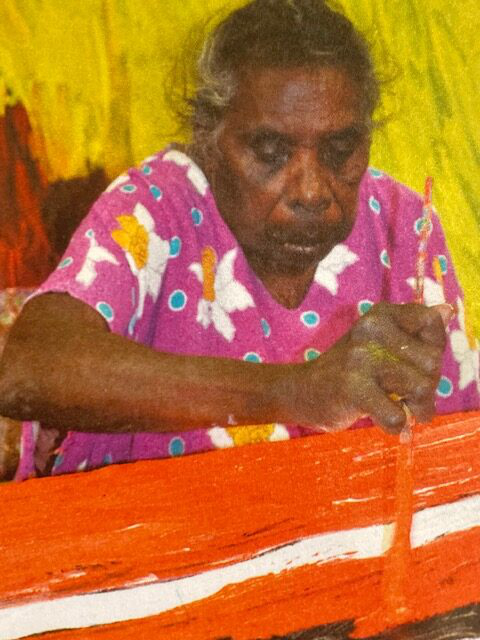

Born to a family of artists, Fujio Yoshida started making art from a very young age, supposedly between 8 and 12 years old. By 1899, she was enrolled in Tokyo’s private school of Western painting, Fudōsha, and became the protégée of her adopted brother and future husband, the artist Hiroshi Yoshida (1876-1950). In times when women seldom had access to an artistic education, she was among the few Japanese women trained to paint in the Western style (yō-ga), whereas her counterparts were usually encouraged to follow a more traditional path (nihonga). She was introduced to the American public in 1903, when she travelled there with Hiroshi, and caught the attention of the critics with her paintings studded with typically Japanese motifs, such as blossoming cherry trees and lotuses. She went on to make her first sales – a rather uncommon feat for a young woman at the time. Her early works consisted mainly of realistic landscapes in watercolour – her favourite medium – (Cherry Blossoms and Bell Tower, circa 1903) reminiscent of Hiroshi’s, both in style and subject matter. Upon returning home in 1907, she took part in the first exhibition organised by the Japanese Academy of Arts and, in 1910, was awarded an honourable mention for her painting Spirit Grove (Kami no mori, date unknown). She began painting still lifes in the 1920s, with a preference for floral motifs (Sweet peas in Vase, circa 1930). She also explored engraving techniques and produced a small number of prints (Roses, 1927). It was during these years that she gradually stepped out of Hiroshi’s shadow to become one of the major figures of the Vermilion Leaf Society (Shuyōkai).

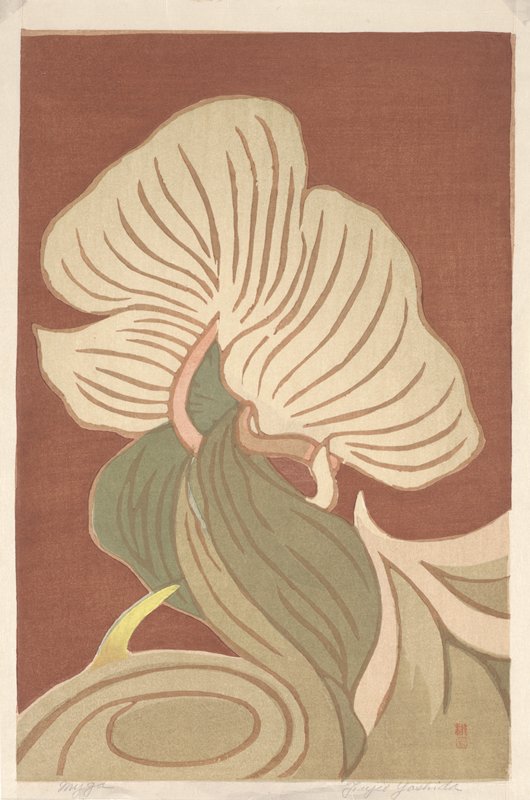

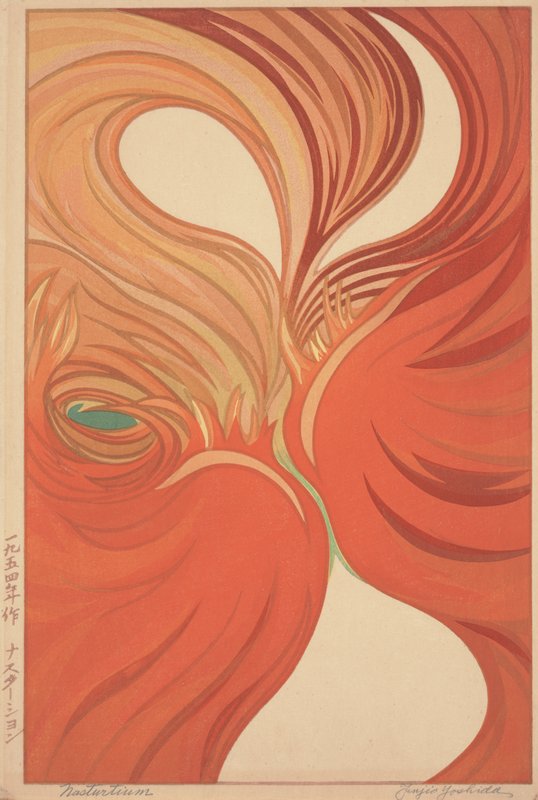

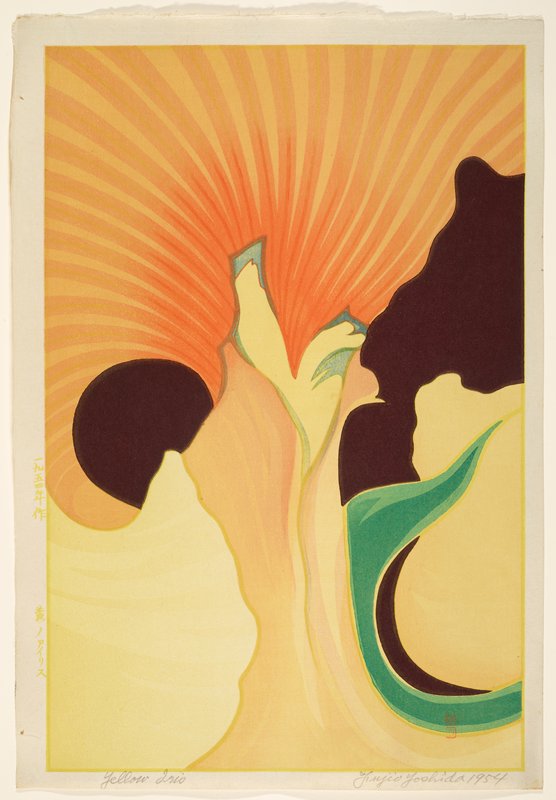

Although she continued to work in a somewhat conservative style in the 1930s and 40s, combining Western aesthetics with more traditional Japanese elements, her output became increasingly bold from the late 1940s. Setting aside watercolours for a while in favour of oil paints, she began to paint depictions of enlarged, close-up flower parts in very bright colours (Flower Iris, 1949; White Flower, 1953). While F. Yoshida’s family now denies any direct influence, her pictures have often been compared to the large flower canvases that Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) began painting in the 1920s. Yoshida’s highly sensual oil paintings represent the perfect transition from her earlier still lifes to her desire to achieve greater stylisation and lean toward “organic” abstraction. They were also the starting point of an incredible series of woodblock prints (Ginger, 1953; Yellow Iris, 1954), which marked the artist’s return to engraving after a near 30-year interruption. While she continued to explore abstraction in the 1970s, she also reverted to her preferred medium and seems to have become more interested in ways of capturing colours, light, and textures than in purely formal issues (Flower, 1973). In 1978, she published her memoirs, Shuyō no ki (The Vermilion Leaf Record), which provide a rare insight into the life of a woman artist in 20th-century Japan. She died in 1987, only days short of her hundredth birthday, at her home in Tokyo.