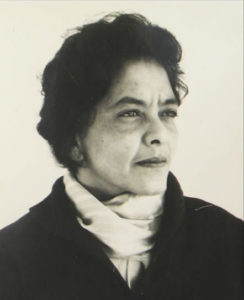

Zubeida Agha

Hasan Musarrat, Zubeida Agha: A Pioneer of Modern Art in Pakistan, Karachi, Foundation for Museum of Modern Art, Arts & The Islamic World, 2004

→Hashmi Salima, Unveiling the Visible: Lives and Works of Women Artists of Pakistan, Islamabad, Action Aid Pakistan, 2002

Zubeida Agha, The National Art Gallery, Islamabad, 1993

Pakistani painter.

The work of Zubeida Agha, who is regarded as “A Pioneer of Modern Art in Pakistan”, is considered feminist, although she herself “hated the term feminist, and was quite angry with the Pakistani painters who identified with this appellation.” But in an interview she conceded that “the sensitive delicacy of her color may owe something to her gender”.

Born in 1922 in a town that later became part of Pakistan, Z. Agha studied Philosophy and Political Science at Lahore’s prestigious all-women Kinnaird College. A recurring dream about painting prompted her to seek formal training in art at BC Sanyal studio in Lahore. Just as she was growing tired of the academic and more conventional style of painting at the Saniyal studios, she had the luck of meeting Mario Perlingieri, a former student of Picasso. M. Perlingieri was an Italian prisoner-of-war interned in Lahore introduced to Z. Agha by her brother, who was a bureaucrat and prominent art critic at the time. Under M. Perlingieri’s tutelage Z. Agha learned to pursue her own inspirations and to paint an object’s idea rather than its objective reality. In 1946, she showed her work for the first time, at a group exhibition at the Lahore Museum, and won awards for both painting and sculpture. Her stylized paintings with abstract titles, such as ‘Wind’, ‘Wisdom’, ‘Metamorphosis’ among others, consciously veered away from recognizable forms and displayed a sense of spiritual harmony. Her first solo exhibition, in Karachi in 1949, shook the foundations of the Pakistani audience’s perception of art. Some were scandalized by what they called a complete lack of skill, while others were in awe of the strangely familiar shapes and forms which “established her as an exceptional colorist”. ‘The cotton pickers’ and ‘In the forest’ are notable paintings from 1949. Here she reworked the figures several times “to arrive at a shape that was simple yet it captured the rhythm of movement and the mood of her subjects”.

Agha won a scholarship to study painting at St Martin’s, London in 1950. Within a year, she transferred to École des beaux-arts in Paris, where she was happier. In 1951-52 she held solo exhibitions at the Trafford Gallery, London, and Galerie Henri Tronche, Paris. Then, she returned to Karachi, where she held two more solo shows. In comparison to her earlier somber color palette, she started to employ more radiant and vibrant colors. The cityscapes painted between 1958 & 70 are full of lights, color and visual noise but devoid of any human presence “like a façade, a false front behind which lurked the emptiness of a wasteland”. In 1961 she was appointed director of Contemporary Art Gallery in Rawalpindi. This gallery is believed to have shown works that were ‘indisputably the best of its era” and laid the foundation for the Pakistan National Art Gallery and the Arts Council in Islamabad, during her sixteen year administration. She was awarded the President’s Medal for Pride of Performance (1965), Quaid-e-Azam Award (1982), Shakir Ali Award (1983) and National Award for Lifetime Achievement in Art (1996). She retired from her formal duties in 1977 and settled in Islamabad, seeking peace and quiet in her work and hosting exclusive exhibitions of her work in her house. Her major solo exhibition was held in 1993 at the National Art Gallery in Islamabad.

Over the years she borrowed and reassembled human figures, horses, landscapes, cityscapes, flowers, objects, geometric shapes, planes and volumes, and strained herself to translate them into a subjective reality outside the realm of time and space. Though the imagery looks simple, joyous and peaceful Z. Agha recounts, “I am in agony when I paint. It is a total mental experience … The creative act is not only an emotional activity. It is only when the emotion is seized by the intellect that the painting starts taking an artistic shape”. Her painting ‘Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony’ remained a landmark for her throughout life and she would jokingly say that she wanted to paint the ninth as well but could only get a gramophone record of the fifth.

Agha lived the life of a recluse. Outside her role as the director of the gallery, she met no fellow artists, except Shakir Ali. In the final period of her life, she grew more inward, insisting on her privacy and discouraging family and friends from visiting too frequently. She never married, dedicating her whole life to the development of her art.