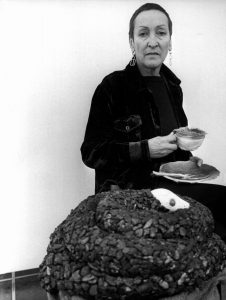

Meret Oppenheim

Pagé Suzanne (ed.), Meret Oppenheim, exh. cat., Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (27 October–10 December 1984), Paris, ARC – Musée d’Art Moderne, 1984

→Corgnati Martina, Meret Oppenheim, Milan, Skira, 1998

→Eipeldauer Heike (ed.), Meret Oppenheim: Retrospective, exh. cat., Bank Austria Kunstforum, Vienne; Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin (March–December 2013), Ostfildern, Hatje Cantz, 2013

Meret Oppenheim retrospective, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 1967

→Meret Oppenheim, Institute of Contemporary Art, London, 1989

→Meret Oppenheim: Retrospective, Bank Austria Kunstforum, Vienna, 21 March–14 July 2013; Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin, 16 August–1 December 2013

Swiss visual artist and poet.

Born from a family of middle-class intellectuals, Meret Oppenheim spent the war years in the Jura region of Switzerland with her mother. Once the conflict was over, her family settled in Steinen, in the south of Germany, before relocating to Basel in 1935. From a very young age, she showed interest in psychoanalysis, a frequent household topic – her father regularly attended Jung’s seminars – and wrote about her dreams. Her mother and grand-mother, suffragettes and feminists, supported her need for independence. The young woman didn’t complete her studies and spent most of her time in the company of local artists. In 1932, she visited Paris with Irène Zurkinden (1909-1987), and attended the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, but preferred writing and drawing in the cafes of Montparnasse, where she met Giacometti, Hans Rudolf Schiess, Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889-1943) as well as Hans Arp and Max Ernst. From 1933 to 1936, her art was shown alongside the surrealists in Paris, Copenhagen, London, and New York. Her artwork not only included drawings, but paintings, collage, assemblage, dream transcriptions, and anthropomorphic objects as well.

In 1933-1934 she posed for Man Ray in a series of erotic photographs published in Minotaure magazine. Starting in 1936, she earned a living by drawing high fashion jewellery and clothing. The same year, the Marguerite Schulthess gallery in Basel presented her first solo exhibition, featuring such important works as Ma Gouvernante, a piece that plays with the ambiguity of objects and the fetishizing of femininity: two upended women’s high-heel shoes are tied up and made to look like a roast on a platter. The artist loved undermining the importance of the creative act. While showing her friends Dora Maar and Picasso one of her creations for Schiaparelli, a bracelet with the inside face covered in fur, Picasso humorously suggested she cover it in fur entirely. This gave her the inspiration for Déjeuner en fourrure (1936), a dining set made of fur, which became one of the flagship works of surrealism, unique and originally poetic. Through a reinterpretation of Duchamp’s ground-breaking work, she thus provided a re-examination of the mundane objects of daily life, and questioned the notions of art and creators themselves. In 1937, completely destitute, she returned to Basel to learn the restaurant trade and make a living. Sensing the imminent arrival of war, she restricted her appearances in Paris to an exhibit at the Drouin-Leo Castelli Traccia gallery, presenting her “Table with Bird’s Feet” with a table top marked by footprints, as well as two other objects. On July 13, 1939, she exiled herself to Switzerland, where the fresh air began to seep into her work, such as in Le Paradis est dans la terre (1940) an upside-down tree dipping into a blue sky at the bottom of a well. She then slowly gave up her work, only to take it up again in 1954. She also questioned her position as both a woman and artist. Feminist, independent, and free, her time in Paris made her understand that she needed to work alone, at the fringe of the macho universe of the surrealists, who treated her like a women-child.

In 1949 she married Wolfgang La Roche, a non-conformist business man. In 1950, she returned to Paris, reunited with her old friends and showed her work in various places. In 1956, she created costumes and masks for a play inspired by one of Picasso’s paintings, Le Désir attrapé par la queue. For the occasion, she exhibited a piece in the Anti-Kunst (anti-art) show in the theatre’s lobby, called Le Couple, consisting of two lace up women’s ankle boots joined together at the toe. In 1959, she organized a banquet in Bern to celebrate the arrival of Spring, symbol of fertility, where food was served on a naked woman’s body.

André Breton invited her to repeat the event in Paris in December 1959 at the Cordier gallery. However, the visual artist would speak out against the voyeuristic attitude of the spectators and thus the passive role adopted by the female body, a far cry from her original intention. Her artistic practice then gained momentum; M. Oppenheim began creating sculptures out of wood and stone and exhibited her work in Italy, Germany, and the United States. In 1967, museums and galleries started organizing large-scale retrospectives of her work.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Documentary on Arte "Meret Oppenheim ou le surréalisme au féminin"

Documentary on Arte "Meret Oppenheim ou le surréalisme au féminin"