Interviews

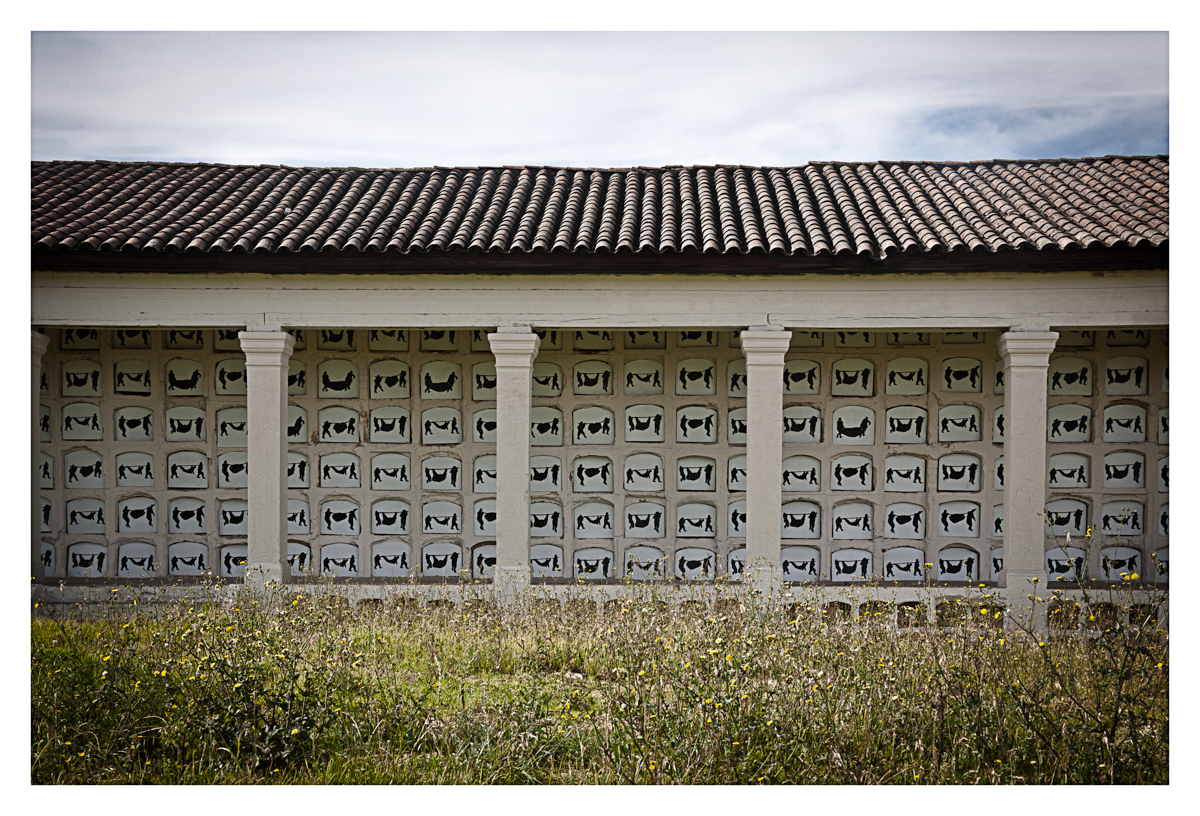

Beatriz González, Auras Anónimas (Anonymous Auras), 2007-2009. Installation on four Columbaria of the central cemetery of Bogotá: 8947 tombstones, silk screen printed on polypropylene plates. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich. Photo: Laura Jiménez

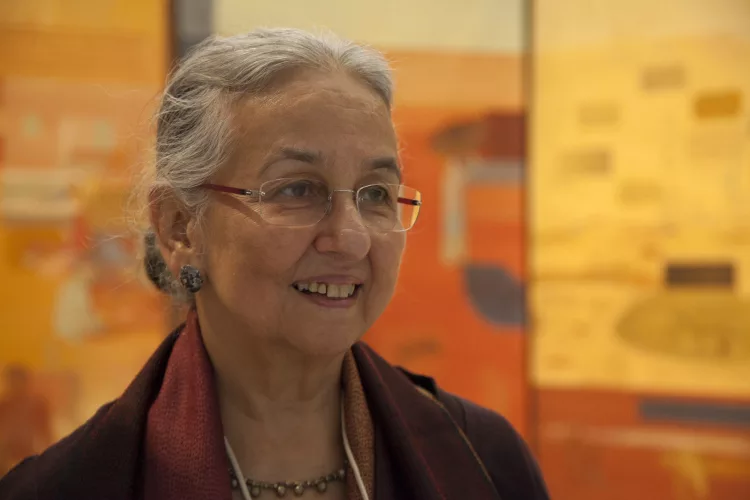

This interview was conducted on 24 January 2017 in the artist’s studio in Bogotá, Colombia. The discussion took place as the artist worked on her paintings depicting the Venezuelan exodus into Colombia. A longer version of the interview can be found in Carolina Ariza’s PhD thesis, “Une mémoire à l’œuvre. Résurgences artistiques de la ‘petite histoire’ en Colombie” (Memory at work. Artistic resurgences of Colombia’s “little history”).

Carolina Ariza: Using Western artworks as your starting point, you turned your attention to Colombian reality. What was it in these images of universal art history that captured your attention?

Beatriz González, Diez metros de Renoir (Ten Meters of Renoir), 1977, oil on paper laid down on canvas, 150 x 1,000 cm. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich. Photo: Oscar Monsalve

Beatriz González, Mural para Fábrica Socialista (Mural for a Socialist Factory), 1981, enamel on wood, 224 x 1,220 cm. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich

Beatriz González: At the beginning I was keen to see how a work rooted in Western art history could be transformed, transfigured, once it reached us here in Colombia. What happens when someone discovers a reproduction of an artwork in a book? In 1977 I painted Diez Metros de Renoir (Ten metres of Renoir), which was inspired by the Bal du moulin de la Galette (1876) by Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), and I sold them by the centimetre. This constituted a performance before the concept even existed in Colombia but after a while I got fed up with the subject. The final painting I completed in this series was Mural para Fábrica Socialista (Mural for a socialist factory, 1981], a reproduction of Guernica (1937) by Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) but flavoured with a few popular local decorative ingredients.

Before that, I had been focusing my research on crimes featured in newspapers. At the time I was working with silkscreen printing and photoengraving but this series of works came to an end with the election of President Julio César Turbay Ayala in 1978. It was at that point that I started cutting out photographs from the written press but it was only in the 1980s that a rift truly occurred in my work.

CA: How did President Turbay’s arrival affect your work? What was the political situation in the country at the time?

BG: Engraving, which had not previously been part of my work, came to the fore. I had also been travelling in Europe, looking at a lot of art; I was familiar with the history of art – in fact I taught it, and this was reflected in my take on the works, although humour was also present and other elements too. When J. C. Turbay came to power, there was still an undercurrent of humour, which lasted right up to the siege at the Palace of Justice in 1985 – but at that point, yes, there was a complete sea change. Until then the politics of the country had been a comedy that I could make fun of in my pictures: I would paint a president decorating a figure, and yet another figure. It stemmed from tragi-comedy but at that moment the curtain opened and all was revealed. All of a sudden the country turned into pure tragedy.

CA: The siege of the Palace of Justice is precisely one of the landmarks that I am most interested in, as it marked a turning point not only in your own work but in the career of many other artists. Was this event a trigger for self-awareness?

BG: Yes, it was as though a veil had been lifted. I hadn’t really been aware, for instance, of drug trafficking; it was only then that I realised just how serious the problem was, how the murders were not all political and all the rest of it. The siege of the Palace of Justice was a seminal moment for me. What struck me most was how justice itself had been killed. It brought to mind the work of Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), The Burghers of Calais (1895),1 I thought about it while “justice was going up in flames”, while 200 people, including judges, were being executed! Initially I tackled the subject of J. C. Turbay with a large dose of humour but I could no longer laugh. So I began depicting people drowning and being swept away by rivers and others who were murdered fully dressed and hurled into the water, crimes perpetrated by the drug traffickers and those same drug traffickers dead. It radically altered that whole aspect of my work.

Beatriz González, Los suicidas del Sisga No 1 (The suicides of Sisga No. 1), 1965, oil on canvas, 120 x 100 cm. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich. Photo: Oscar Monsalve

CA: One of your paintings particularly caught my attention, the one devoted to human rights defender Yolanda Izquierdo. How do you obtain access to this kind of information? How do you go about your research?

BG: When I saw the photo of Yolanda Izquierdo taken by Álvaro Sierra, published in the magazine Semana, it made a huge impression on me. I knew Á. Sierra, so I rang him to ask if I could use his photo and began looking into this woman. I was drawn by the story because it raised an issue of dual morality for the people of the Montería region: it revolved around the figure of Carlos Castaño, a paramilitary leader who was both a murderer and the person who provided their land. When C. Castaño died, his family turned up with the intention of taking back the peasants’ land but the men and women would not let them. Yolanda supported them and she became a genuine defender of human rights. But C. Castaño’s people had her killed. What I’m trying to say is that the root of the problem is neither black nor white; the lines are really blurred. I found myself very intrigued by the story although I don’t normally read about this kind of thing in the newspapers; it’s mainly the image that speaks to me. I saw this image and said to myself: “More Suicidas del Sisga.”2 I started wondering about the dreams she might have had, I thought she probably aspired to live in a house surrounded by plantations. On the photo, the background showed the valley but instead of drawing that valley I portrayed people harvesting or fishing by night. On another snapshot, she was preparing a bowl to grind corn. I imagined four more of her dreams and gave them form. I got a lot of pleasure from that. She was a truly moving figure because she was such a courageous woman. I was told she used to say “They’re going to kill me” and they did. It was Y. Izquierdo who enabled me to find poetry in tragedy.

CA: Today a large number of women human rights defenders are also Yolanda Izquierdos and are still being assassinated; it’s a never-ending story in Colombia…

BG: Yes, defenders, men and women, are still being killed. I always cut out their photos because it’s so ghastly. Ten have been murdered already.3 But I believe in Peace with a capital P, I believe because I don’t see how we can spiral any further into violence.

CA: Do you believe the Peace Agreement constitutes a decisive development in the history of your country?4

BG: Yes, I think this is an historic moment we’re living through because it’s not simply a presidential whim, there are some intelligent experts out there. Take Sergio Jaramillo:5 people like him who know all about literature, philosophers. One of the determining factors was to get out of Colombia and move to Havana, and once that had been done to surround themselves with thinkers, because the guerrillas are barbarians, although we’re beginning to bring them into line. I believe in this process. The experience has gone on for so long and has been filled with such violence, and we’ve always clung to the idea of having a really powerful army to kill these barbarians, but it’s never actually happened.

CA: Did the agreement represent a turning point in your work, like the siege of Palace of Justice?

BG: I’ve asked myself this question so many times, because I believe one needs to pay attention to one’s Oeuvre. So it frightened me. I wouldn’t want to compromise my work on account of this event. The historic impact of the agreement is totally different from the siege of the Palace of Justice, which had such a sad dimension. I don’t want to tackle that theme any more.

CA: Yes, the transition has taken a very long time. Your work has also been marked by incredibly powerful images of women who have lost their children. Could you tell me a bit more about this?

BG: The work is called Las Delicias (1996).6 At the time, I was involved in a number of projects linked to natural disasters. I was working on faces of people crying and it was at that point that the massacre of Las Delicias took place, followed by that of Patascoy.7 When I saw the press photographs of Las Delicias, I noticed there were stakes in the camp that the guerrillas used to tie up the soldiers before taking them hostage, leaving others dead. There were about 120 of them and they captured 60, so I became very involved in the scene of the camp although I realised I could not simply depict it through a photograph of burned stakes. So I began to represent women in tears, based on images of women hiding their faces following the death of their loved ones. It so happens that a photographer once took a picture of me without my consent and my reaction was to say “Don’t do that!” while hiding my face. So it seemed to me that this act could symbolise the grief that was lacking in the press photo of the massacre, in which one could see a lot of women crying. I tried to find photos of women crying and covering their faces but as I couldn’t find any I composed most of the paintings using the picture taken by the photographer without my permission. I included 35 of these invented portraits for an exhibition. It was astonishing, people were coming out of the exhibition in tears. It had never happened before. A gesture as basic as covering one’s face with one’s hands made perfect sense.

Beatriz González, Autorretrato desnuda llorando (Nude Self-portrait in tears), 1997, oil on canvas, 160 x 45 cm. Photo: Juan Camilo Segura/Juan Rodríguez Varón

CA: In a way, women have actually always been excluded from the writing of history or politics.

BG: Yes, but there was something else here: it was the first time that women had gone outside to make their voices heard, like on the Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires or the Plaza de Bolívar in Bogota. This had never happened before and I found it extraordinarily moving. I went there myself and it seemed somehow unreal, they had a sort of stick onto which they had fixed their banners. These women were demonstrating, and it was an unprecedented act in Colombia at the time.

CA: Was it really an unacknowledged reference to their battle against their children having disappeared?

BG: Yes, to their children disappearing. It was beautiful, because afterwards we were able to hear them on the radio as well. Today, now that her status as a victim has been recognised, that woman who has been waiting for so many years has the right to speak out; she is waiting for her son and her son dies from disease, out there in the depths of the forest. As for the Mono Jojoy concentration camps,8 although I never dared depict them it was devastating: the people were standing there behind barbed wire fencing, it was unbelievably cruel.

CA: Did you sometimes venture into the field or was your reference always through the press?

BG: My reference is the press and only the press. It became fashionable at one time for all those society ladies, such as Gloria Zea and Elvira Cuervo, to go and talk to the guerrillas in situ; it was a revolting spectacle. So the press provided me with my material but at the same time I was able to stand back, I stayed outside the media circus.

CA: In your view, how can the artist conceivably play a part in writing history?

Beatriz González, Naturaleza casi muerta (Still life almost dead), 1970, enamel on metal plate mounted on metal bed, 125 x 125 x 95 cm. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich. Photo: Laura Jiménez

Gráfica Molinari #227. Thumbnail, Gráficas Molinari

BG: I once read, although I can’t remember who coined the phrase, that “art says what history is unable to tell”. I could really relate to that. When I was at the Museo Nacional, the fact that I was working in an institution was tremendously important to me. I never stopped painting but I was also a curator, which enabled me to review the history of art in Colombia. I believe that even if a work of art does not feature illustrious figures or depict historic events, it carries its own language to express national reality and therefore history.

CA: What’s happened with history in Colombia, how come we have such an abstract or fictional relationship with it?

BG: I don’t know, historians of both sexes just seem to get crazier and crazier,9 and what’s more they have so many theories. They were throwing the museum into confusion when I left: there were some really strange things going on. I think historians are venturing into some really dangerous waters. I don’t know.

CA: You don’t think it has something to do with the glut of violent images to which we’ve been subjected?

Beatriz González, Cargueros (#3), serie Vistahermosa, 2006, sanguine on paper, 28 x 35 cm. Photo: Juan Camilo Segura

Beatriz González, Cargueros de Bucaramanga, serie Vistahermosa, 2006, oil and charcoal on canvas, 25 x 815 cm. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich. Photo: Oscar Monsalve

BG: No, absolutely not. The images sustain us artists rather than the historians. The latter don’t even see them; they barricade themselves behind their theories, incredibly abstract theories as you said, and they don’t look at the images. We’re the ones who look at them. It’s certainly true that with so many repetitions the image becomes denaturalised. It was for that reason that I conceived the installation Auras Anónimas (Anonymous auras, 2009) in the main cemetery in Bogotá. As it happens, it’s now collapsing, thanks to the mayor of the time, Enrique Peñalosa, who refused to allow anything to be done because he wanted to destroy the columbaria. I always say that although the media get those images out there, they are also perfectly prepared to see them fade from popular memory. It’s like trying to capture a flash; they don’t remain fixed in our memory; on the contrary their importance diminishes. All the research I carried out with regard to the corpse bearers in the work Auras Anónimas therefore stemmed from the assumption that an image that appears in a newspaper will be thrown into a dustbin in the street the following day. If someone keeps it and reads something into it, it will be saved – but as so many are produced lots end up getting lost. You’re quite right, it’s because there is such a plethora that the image gets devalued.

CA: Turning to your archives, I’d really like to know how you set them up. For instance, I would forward a hypothesis that Doris Salcedo has more archives on the history of Colombia than any other historian; she has an extraordinarily powerful obsession with the Palace of Justice. In your case, you have followed a number of less dramatic events but when placed end to end they must also generate some truly interesting elements. Could you tell us a bit more about your archives?

BG: They are colossal. José Ruiz, my assistant, discovered them when he was working on my catalogue raisonné and he is in the process of putting them in order. Absolutely everything is in those archives. One section is personal and relates to my career – it includes my photos, my sources, everything – while another has nothing to do with my work and is more specifically oriented towards the theme of violence, but I have never used it. They are extremely interesting elements – we’re considering how to use them – but also very curious. For example, I have masses of T-shirts because at one stage, in my role as art historian, I worked as an educator. In the 1970s I used to cut out anything that contained the word “art”, so my poor assistants are now trawling through all the bags I had kept at home.

CA: Did you keep these archives because you knew you would need them at one point for your work or because you wanted to preserve the memory of the events that were taking place in Colombia at the time?

BG: It depends on the context. I keep certain archives because they correspond to things that will never be repeated – so I want to preserve them – and others because they concern my artworks – which is different – and yet others because they are linked to the cultural situation. So my archives are a pure folly. They don’t belong to someone who has only ever devoted themselves to a single subject.

This bronze group depicts six leaders of Calais during the Hundred Years’ War. Following an eighteen-month siege by Edward III, in 1346 the English king offered to free the city in exchange for six of its leading figures. Though they expected to be executed, the men’s lives were eventually spared. The city of Calais commissioned the bronze from Rodin in 1884.

2

Los Suicidas del Sisga (The suicides of Sisga) is one of the artist’s most iconic works. She drew her inspiration from a picture she came across in the popular news section of the newspaper El Tiempo. It features a small, rather blurred photograph, depicting a modest couple holding a bunch of flowers. The story is a moving one: he was a gardener; she a maid. The couple believed the world was too cruel to encompass their love for each other. They therefore made their way to the Sisga dam where they committed suicide. They took this photo beforehand to give their families something to remember them by. What really attracted the artist, before discovering the actual story, was the flatness of the image, its lack of colour and its inexpressive quality.

3

When this interview took place, in January 2017, only two months had elapsed since the signature of the Peace Agreement. According to UN reports, in 2018 there were 172 homicides among community leaders and human rights defenders, 46 more than in the previous year. In 2019, 107 human rights defenders were murdered in Colombia.

4

Peace Agreement between the state and the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – People’s Army), signed in Havana in November 2016.

5

Sergio Jaramillo Caro, philosopher and philologist, High Commissioner for Peace from 2012 to 2016. Together with Humberto de la Calle, the national government’s chief negotiator, they were appointed to spearhead in its entirety the conceptual strategy of the FARC peace process until its completion in August 2016.

6

The siege of Las Delicias was an attack perpetrated on 30 August 1996 by FARC guerrillas against a military base held by the Colombian Army in the region of Putumayo. The attack, led by some 450 guerrillas, left 27 soldiers dead and 16 wounded, while 60 others were taken hostage. This was one of the most damaging setbacks experienced by the Colombian state forces in their struggle against the FARC. The hostages were freed ten months later, on 14 June 1997.

7

The siege of Patascoy was carried out by the FARC on 21 December 1997, between the regions of Nariño and Putumayo. The FARC, with approximately 150 to 200 men, attacked the military base occupied by a section of the infantry battalion and including an army communications centre. In the course of the attack, which only lasted about a quarter of an hour, 10 soldiers were killed and 18 taken hostage. In 2001, 16 were freed while two of them, Libio José Martínez and Pablo Emilio Moncayo, were held prisoner for over ten years. The former, an army chief, was assassinated on 26 November 2011.

8

Víctor Julio Suárez Rojas, more often known as Jorge Briceño Suárez or Mono Jojoy, was the second-in-command of the FARC. He was assassinated in the Serranía de la Macarena on 23 September 2010.

9

B. González is referring here to art historians.

Carolina Ariza is an exhibition curator and researcher. In 2018 she defended her PhD thesis at the Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, on the artistic resurgence of secondary histories in Colombia in the wake of the siege of the Palace of Justice in 1985. In 2019 she was a finalist for the Centre National des Arts Plastiques (CNAP) research grant, awarded to art theoreticians and critics, following the development (publication and exhibition) of her project Tisseuses de mémoire. Les artistes femmes et leur participation à l’écriture de l’histoire (Memory weavers: Women artists and their involvement in writing history). She curated the exhibitions Tisseuses de mémoire (Espace Arte Faktos, Paris, 2019) and Murmures et visions. Une déambulation en Amérique latine (IESA Arts & Culture, Paris, 2016); she was also in charge of the Latin American section of Solo Projects at the SWAB Art Fair in Barcelona (2014 and 2015) and was appointed research supervisor for Latin America at the Musée National d’Art Moderne – Centre Georges-Pompidou for the “Research and Globalisation” project. She also contributed to the acquisition of Antonio Caro’s piece Aquínocabeelarte (Artdoesnotfithere, 1972) by the Musée National d’Art Moderne – Centre Georges-Pompidou.

Beatriz González & Carolina Ariza, "Beatriz González: From the Dismantling of Universal Iconography to Provincial Singularity." In , . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/beatriz-gonzalez-du-demontage-de-liconographie-universelle-a-la-singularite-provinciale/. Accessed 31 January 2026