Maria Margaretha van Os

Klarenbeek, Hanna, “Maria Margaretha van Os (1779–1862)”, Digitaal Vrouwenlexicon van Nederland, Huygens Instituut, 2014

→Loo, Sophie van, ‘The forgotten accomplishments of the painter duet Maria Margaretha van Os (1779–1862) and Petronella van Woensel (1785–1839), or how two Dutch women artists in the first half of the nineteenth century befriended one another and decided to dedicate their lives to still-life painting’, Jaarboek Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten [Royal Museum of Fine Arts Yearbook], (Antwerp 2000), pp. 231-263.

→Hoogenboom, Annemieke, De Stand des Kunstenaars: De positie van kunstschilders in Nederland in de eerste helft van de negentiende eeuw [The State of the Artists:Artists’ position in the Netherlands during the first half of the nineteenth century], Leiden (Primavera Pers) 1993.

Elck zijn waerom: Vrouwelijke kunstenaars in Nederland en België 1500–1950 [To Each their Reasons: Women artists in the Netherlands and Belgium, 1500-1950], Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp, October 1999–January 2000.

→De Vrouw 1813–1913 [The Woman 1813-1913], Meerhuizen, Amsterdam, May–October 1913.

→Lijst der kunstwerken van nog in leven zijnde Nederlandsche meesters, welke zijn toegelaten tot de tentoonstelling van de jaren 1814 [List of works of art by living Dutch masters admitted to the exhibtion of the years 1814], The Hague, September–October 1814.

Dutch painter.

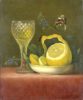

Born in The Hague, Dutch painter Maria Margaretha van Os received great recognition during her life for her floral still life paintings and drawings. Similar to her father, the still life painter Jan van Os (1744–1808), she depicted voluminous bouquets, often accompanied by fruit, flowers or seashells on a marble table top. In addition, she painted more subdued still lifes, mostly consisting of fruit and tableware, such as Still Life with Lemon and Cut Glass (1823–1826). This simple composition places the group of objects at the centre of the canvas, transmitting a romantic atmosphere through the use of a soft colour palette. Her realistic painting technique is expressed through the precise execution of the different materials, such as the textured glass reflecting the lemon peel.

Like her brothers, Pieter Gerardus van Os (1776–1839) and Georgius Jacobus Johannes van Os (1782–1861), she was taught the principles of painting in the family atelier. As her mother, Susanna de la Croix (1755–1789), was also talented with pastels and drawing, it is very likely that she was trained by both parents.

In the early nineteenth century, Dutch art institutions slowly opened their doors to women artists, reflecting a broader development in Europe where women artists were claiming a position in the art world. As a result, the Tentoonstelling van Levende Meesters [Exhibitions of Living Masters], a series of biennial exhibitions held in a number of Dutch cities, allowed women artists to exhibit their artworks. Inspired by the French Salon, these exhibitions offered contemporary artists the chance to display and sell their works to a large public of art enthusiasts and collectors. In 1814, M. M. van Os used this opportunity to exhibit her works in The Hague. In the coming years, more women artists followed, such as her good friend Petronella van Woensel (1785–1840) and Elisabeth Liosetta Hoopstad (1787–1847).

Through these exhibitions, she established a position in the art market, which resulted in her appointment in 1826 as an honorary member of the Akademie Voor Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam. Since women were not granted regular memberships, from 1801 onwards, the Academy would award honorary membership, especially to women artists who possessed great artistic skill.

For over thirty years, she submitted flower and fruit still lifes annually to the Tentoonstelling van Levende Meesters, occasionally showcasing a landscape or study of a bird or insect. Two Hyacinths (1823) is a good example of the type of artwork she submitted. Compared to other male and female participants at that time, she exhibited an unusually high number of artworks. A signed flower still life from 1860 shows that she was still actively painting until her death in 1862, at the age of 83. Despite her death certificate stating that she was “without a job”, the large number of artworks she exhibited and the appreciation of her artistic skills by contemporaries clearly demonstrate the contrary.

A biography produced as part of the programme “Reilluminating the Age of Enlightenment: Women Artists of 18th Century”

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2024