Research

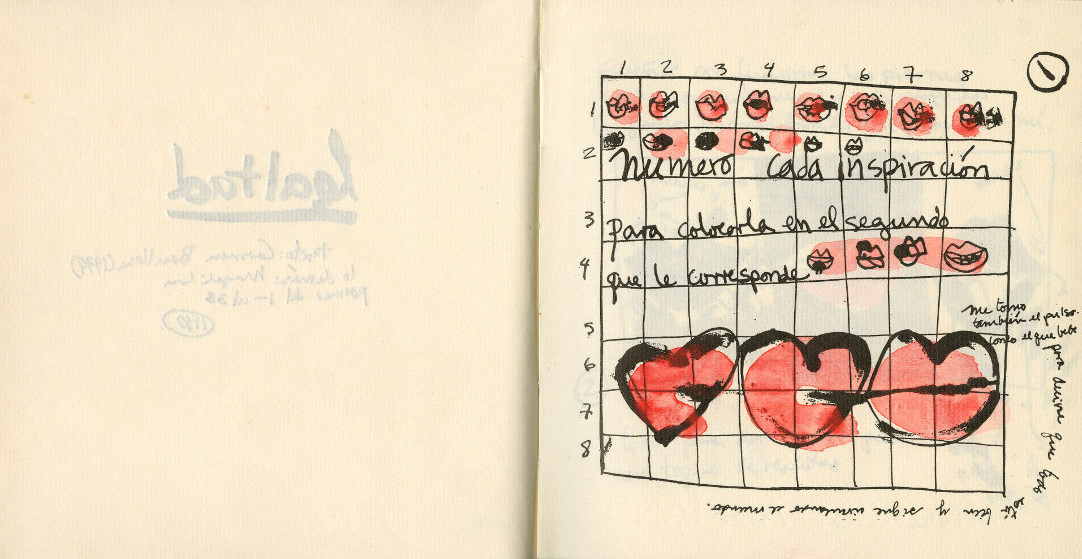

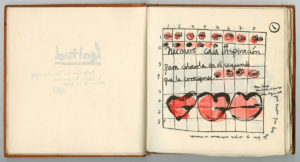

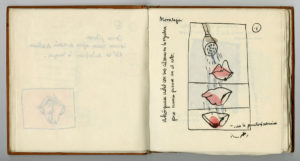

Magali Lara and Carmen Boullosa, excerpt from Lealtad [Loyalty], 1980, offset impression on paper, 16 x 17 cm, Courtesy Magali Lara and Centro de Documentación Arkheia, Museo Universitario Arte Contempóraneo, Mexico City

It is well known that history has by and large been written from the perspective of the patriarchy. In 1980s Mexico City, a group of women artists sought to destabilize the continuation of this one-sided interpretation by infiltrating the source of historical narrative: the archive. In this article, I argue that the collaborative artists’ books by artist Magali Lara (born in 1956) and writer Carmen Boullosa (born in 1954) were an informal investigation into auto-archiving female history.

In doing so, I aim to explore how their experimental art practices in Mexico foreshadowed the establishment of Pinto mi Raya, an artistic project founded in 1989 by Mónica Mayer (born in 1954) and Victor Lerma (born in 1949) that includes an immense archive dedicated to female and feminist artists. Throughout the 1980s, M. Lara and C. Boullosa created artists’ book that document, verbalise and visualise a subjective female experience.1 Without characterizing M. Lara as a feminist artist or C. Boullosa as a feminist writer, this article examines how their collaborative act of auto-archiving created the opportunity to establish and circulate new forms of knowledge based in the historically marginalized female perspective.

From the beginning of her career, M. Lara was aware of the importance of archiving herself and her work, and her friendship and collaboration with Mónica Mayer was crucial to this approach. While studying at the Feminist Studio Workshop in Los Angeles in the late 1970s, M. Mayer was immersed in a space dedicated to women that emphasized the importance of Consciousness-Raising (C-R).2 This ideology, which was central to second-wave feminism in the United States, focused on the verbalization of individual experience as a strategy to interrogate how subjectivity interconnected with the social world and how that subsequently impacted women’s lives.2 At the start of the 1980s M. Mayer returned to Mexico City where an array of artistic activity dedicated to concretizing female-centric knowledge was emerging. While she contributed significantly to this endeavour, so did Lara and Boullosa with their artists’ books.

A vessel for politically engaged art due to its inexpensive production and distributive possibilities, the artist’s book has historically remained on the periphery of institutionalization, therefore permitting greater autonomy of expression for artists and publishers. This is true of M. Lara and C. Boullosa’s work with the medium, which interrogates patriarchal concepts of femininity and domesticity while proposing their own positions on what it means to be a woman. Broadly speaking, the artist’s book can be a unique work or in a series of editions, but either way it often unifies word and image, integrating the formal production with aesthetic ideas.4 In Mexico it has a long history in illustrated broadsides and magazines that circulated socio-political ideologies, an approach that continued to intensify up to the 1970s when the medium became popularized by Mexican artists Ulises Carrión (1941-1989) and Felipe Ehrenberg (1943-2017). In 1969, F. Ehrenberg and artist Martha Hellion – who were then married – left Mexico for England where, with British historian David Mayor, they founded the experimental centre and publishing house Beau Geste Press and produced artists’ books by U. Carrión, Carolee Schneemann (1939-2019) and Cecilia Vicuña (born in 1948), among many other international artists.5 In particular, Vicuña’s 1973 Saborami highlights the early use of the artist’s book for self-reflection and archival purposes: it is filled with diary prose from the months leading up to the Chilean coup that overthrew Salvador Allende, along with newspaper clippings, collages and reproductions of her own paintings.

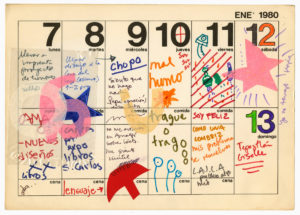

Magali Lara, Artist’s book in the form of a calendar-day planner, 1980, clippings, letters, notes, drawings and photographs, 26.6 x 18.7 cm, Courtesy Magali Lara and Centro de Documentación Arkheia, Museo Universitario Arte Contempóraneo, Mexico City

After living abroad for five years, F. Ehrenberg returned to Mexico and was invited to give classes at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas in Mexico City, where M. Lara was enrolled at the time. Although she became aware of his work and the activities of Beau Geste Press, Lara never studied with F. Ehrenberg directly, as she was more interested in artists’ books in the form of the French livre d’artiste which, as she describes, give the poem and the image equal importance.6 Her knowledge of and divergence from F. Ehrenberg’s practice is clear in an untitled project from 1980, in which she organised and reflected on her life through a day-planner. Part of a widespread trend of visual writing that adopted a confessional tone, the diary and its first-person narrative had long interested M. Lara.7 Taking unadorned calendar pages, M. Lara scheduled meetings, noted important birthdays and scribbled down to-do lists. In addition to these ordinary notations, she disrupted the gridded and stale schema with drawings, poetry and collages that spill across the borders of the itemized days. On the page from 7 to 13 January, Lara noted that she had to take drawings to the Casa del Lago (a cultural centre in Mexico City’s Chapultepec Park), but also filled in boxes with colourful amorphous drawings, reflected on her emotions that day, and collaged the page with paper cut-outs. The tone shifts from serious to comical, particularly implementing the written word for humour while breaking down the divisive structure of the calendar. In one box, M. Lara writes, “Como una lombriz” [I eat a worm], which combined with the text directly above in a different box becomes “Soy feliz como una lombriz” [I am happy like a worm].8

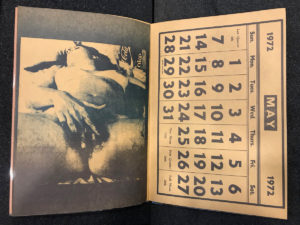

Felipe Ehrenberg, pages from Pussywillow: A Journal of Conditions, published by Beau Geste Press, United Kingdom, 1973, Jean Brown Collection, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (93-B2489)

M. Lara’s subversion of the calendar recalls F. Ehrenberg’s own artist’s book Pussywillow: A Journal of Conditions (1973), which in parts juxtaposes an unmarked calendar page with a print of a woman pleasuring herself, an image that directly evokes the male gaze of Gustave Courbet’s Origin of the World (1866) and Marcel Duchamp’s Étant donnés (1946–1966). Destabilising such perspective, Lara’s calendar is exclusively from her own point of view. She uses image and word to document both special and quotidian events, and thus contributes to overturning the historically simplistic and patriarchal depiction of women.

Magali Lara and Carmen Boullosa, excerpt from Lealtad [Loyalty], 1980, offset impression on paper, 16 x 17 cm, Courtesy Magali Lara and Centro de Documentación Arkheia, Museo Universitario Arte Contempóraneo, Mexico City

The same year that she made the calendars, in 1980, M. Lara executed the first of many collaborative works with C. Boullosa by converting Lealtad [Loyalty], a series of Boullosa’s short poems, into an artist’s book. The two had been introduced in 1979 by their mutual friend, the performance artist Jesusa Rodríguez (born in 1955). Bringing together text and image, their collaboration discloses not only the interdisciplinary nature of their shared projects but also the mutual support that the two have fostered over four decades as they continue to work together. They began their joint endeavor with hand printed books at the renowned Taller Martín Pescador, which at the time was also publishing texts by Octavio Paz, Charles Tomlinson, and Roberto Bolaño, among others. Soon after, in 1982, C. Boullosa established a print shop in her home under the name Taller Tres Sirenas. C. Boullosa and M. Lara would also work with many other cultural figures in Mexico, inviting national and international artists and writers to engage with their projects through prose, artists’ books, exhibitions and performance.

Magali Lara and Carmen Boullosa, excerpt from Lealtad [Loyalty], 1980, offset impression on paper, 16 x 17 cm, Courtesy Magali Lara and Centro de Documentación Arkheia, Museo Universitario Arte Contempóraneo, Mexico City

Uniting C. Boullosa’s poem with M. Lara’s drawings, Lealtad meditates on the relationship between violence and female sexual identity. The artists’ book is filled with pages that feature loosely written text along with images of lips and hearts that often morph into grotesque abstractions. On the first page, rounded lip-shaped hearts (or heart-shaped lips) and free-form text refute structure by spilling across the boundary of the grid, which itself is slightly asymmetrical. While M. Lara’s drawings in Lealtad insinuate an exercise of disobedience to imposed criteria, alongside C. Boullosa’s poem the work reveals the tenuous line between loyalty and abuse. On the seventh page of the book, a shower head spits water onto a pair of disembodied lips that mutate into bloody undergarments as they progress down three registers. C. Boullosa’s poem begins to the left, reading “Moraleja: ahórquese usted con sus calzones en la regadera/pero nunca piense en el acto:/eso le permitiría sobrevivir” (“Moral: strangle yourself with your undergarments in the shower/but never think about the act:/that would allow you to survive”). Bringing together the deceivingly docile images of the showerhead and lips with the depiction of blood-stained underwear and a violent interior monologue, the page communicates a wholly subjective depiction of sexual violation. These domestic objects are part of Lara’s own iconography, one that art historian Andrea Giunta suggests is implemented “as a point of departure for an autobiographical investigation”.9 Throughout her career, M. Lara has built up an extensive lexicon of objects such as chairs, scissors and home appliances. These household items often stand in for the female body so as not to reproduce the very image that has been co-opted by the male gaze, while also alleviating the severity of the narrative through humour.

M. Lara and C. Boullosa’s artists’ books from this period, in their form and content, continue to explore the auto-archival practices that Lara had experimented with in her day-planner. By collaborating with one another, Lara and Boullosa collectively communicated and documented underexplored and often ignored aspects of a life lived daily by women. While I am not proposing that Boullosa and Lara were directly referencing the Consciousness-Raising ideology implemented by second-wave feminism, I do suggest that verbalisation, and in this case also visualisation, of the subjective contributed to a greater social network of women, who subsequently established new forms of female-centric knowledge through the act of auto-archiving.

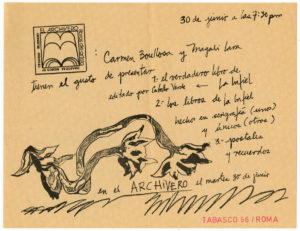

Invitation to the opening of Los Libros de la Infiel [The Books of the Unfaithful] at El Archivero, c. 1986, cardboard, 25 x 14 cm, Courtesy Magali Lara and Centro de Documentación Arkheia, Museo Universitario Arte Contempóraneo, Mexico City

Seven years after they completed Lealtad, Boullosa and Lara exhibited Los libros de la Infiel [The Books of the Unfaithful, c. 1986], their multi-part collaboration based on Boullosa’s series of poems that are collectively titled La Infiel. The project – which is composed of several unique and limited edition artists’ books including La Enemiga [The Enemy] and La gigante [The Giantess] – was shown at El Archivero, the experimental bookstore and exhibition space run by Yani Pecanins (1957-2019), Gabriel Macotela (born in 1954) and Armando Sáenz (1955-2018) in Mexico City’s Roma Norte neighbourhood. Once again confronting the notion of fidelity, the series challenges, among many subjects, idealized perceptions of femininity and the expectations placed upon women.

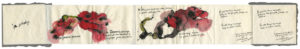

Magali Lara and Carmen Boullosa, La enemiga [The Enemy] 1986, ink and watercolor on paper, 15.5 x 16 cm, Courtesy Magali Lara and Centro de Documentación Arkheia, Museo Universitario Arte Contempóraneo, Mexico City

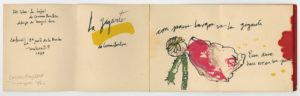

Magali Lara and Carmen Boullosa, La gigante [The Giantess], 1987, seriegraph and ink on paper, 1987, 12.5 x 12.5 cm, Courtesy Magali Lara and Centro de Documentación Arkheia, Museo Universitario Arte Contempóraneo, Mexico City

In La enemiga (1986) text and image portray the advantage of fluidity, of not restricting oneself to, as Boullosa’s poem reads, “color, forma, o género distinguible” (“distinguishable colour, form or gender”). In other words, confining oneself to the feminine makes a person less complex, more predictable, and therefore less cunning. Lara’s watercolour flora simultaneously convey mutability as they bleed beyond the limits of their black outline and overflow from one page of the leporello-bound book to the next. Executed in the same accordion format, La gigante (1987) continues the story of a woman who does not remain faithful to the expectations placed upon her. At the beginning of the poem, the subject is a giantess who makes loud noises as she walks and would have to “inclinarse para entrar en cualquier puerta” (“bend over to enter any door”). The perspective of the poem changes swiftly from the third person to the first as the speaker herself takes on the role of the giantess, declaring she would have to “encogerme para caber bajo cualquier techo” (shrink to fit under any roof). With this shift in point of view, the work adapts an autobiographical perspective of a woman who does not fit into the interior spaces in which she is expected to be. M. Lara and C. Boullosa certainly were not alone in their desire to document their position as women who would not be silenced or domesticated. First realised in 1978 at Mexico City’s Museo de Arte Moderno, Mónica Mayer’s ongoing project El Tendedero [The Clothesline] invites women to freely express themselves through the act of writing down their experiences with violence and harassment on a piece of paper that then hangs in public for all to read.

La enemiga and La gigante, along with Lealtad, are objects that inscribe a tacit reality that women often face but that were widely ignored, particularly in the period under consideration. Such evasiveness can be discerned in the subjects confronted by Los Grupos, the male-dominated art collectives that began in 1970s Mexico and broached a variety of timely political topics but stayed away from “women’s issues”.10 M. Lara and C. Boullosa’s practice of auto-archiving in the works discussed in this article undermines the patriarchal idea of the woman as compliant and domestic and, more subtly, documents that these issues were actual struggles faced by women. Beyond the content within La enemiga and La gigante, the very format of these artists’ books proposes a deviation from the norm. The leporello binding creates multiple viewing possibilities, many of which stray from the typical way to read a book. Furthermore, as books, these works are inevitably based in a medium that is intended to circulate, to break free from a confined space so as to move from one hand to the next.

Martha Barratt proposes that the auto-archival practice can destabilize Jacques Derrida’s formulation of the “patriarchal foundations of the archive”.11 Lealtad, La enemiga and La gigante demonstrate how with their auto-archival practice, M. Lara and C. Boullosa disputed patriarchal structures through the collective verbalisation and visualisation of female subjectivity. That they do so through a medium that is intended to circulate further subverts these structures of power. Although artists’ books are not the only means by which women artists have acted to overthrow the patriarchy, the compact and portable nature of the medium provided ample opportunities for movement.12 Throughout the 1980s, M. Lara mailed some of the artists’ books—both those made in collaboration and on her own—abroad, to fellow artists, including Ulises Carrión in Amsterdam.13 Her utilisation of the postal service reveals how these artists’ books were also part of the mail art movement, which allowed international artists to circumvent institutions, curators, dealers and, as is common in the case of Latin America during the Cold War, oppressive political regimes.14 Through their ability to critique and bypass patriarchal structures—whether it be art institutions or dictatorships—artists’ books produced by women in Mexico were often a means by which to both store and share women’s subjective experiences.15

Interestingly, today many of M. Lara and C. Boullosa’s artists’ books, along with other auto-archival projects, have been incorporated into the Centro de Documentación Arkheia, part of Mexico City’s National Autonomous University. The institution has excellently conserved and catalogued these works, making them available for researchers such as myself. Their current location, however, inevitably raises questions for future exploration, particularly: what happens when an auto-archival, anti-patriarchal object becomes incorporated into the very institutional system that it initially evaded?

Madeline Murphy Turner is a PhD Candidate at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, where she focuses on modern and contemporary art from Latin America. Her dissertation examines women’s collective artists’ books, galleries, theatre and spectacles in contemporary Mexico. She is the recipient of the 2019–2020 Marica and Jan Vilcek Curatorial Fellowship, which she will complete at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. From 2017 to 2018, she was the Graduate Curatorial Assistant at the Grey Art Gallery, NYU. Madeline has also taught courses in NYU’s Department of Art History and Steinhardt Department of Art and Art Professions, and has published articles in The Brooklyn Rail, Damn Magazine, Hyperallergic and Art Margins.

Barratt Martha, “Autobiography, Time, and Documentation in the Performances and Auto-Archives of Carolee Schneemann”, Visual Resources 32, 2016, nos 3-4, pp. 283-284.

2

McKelligan Hernández Alberto, “Pinto mi Raya (I Draw My Line): Feminist Archival Practices in Contemporary Mexican Art”, Nierika, July–December 2016, no 10, p. 16.

3

Sorkin Jenni, “Learning from Los Angeles: Pedagogical Predecessors at the Woman’s Building”, in Doin’ It Public: Feminism and Art at the Woman’s Building, eds Meg Linton and Sue Maberry, Los Angeles, Otis College of Art and Design, 2011, p. 49. Quoted in McKelligan Hernández Alberto, p. 16.

4

Drucker Johanna, A Century of Artist’s Books, New York, Granary Books, 2004, p. 2. For further discussions of the artist’s book, see Martha Hellion, Isaa María Benítez and Ulises Carrión, Artist’s Books, Vol. 1 & 2 , Madrid, Turner, 2003; Lyons Joan (ed.), Artist’s Books: A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook, New Yor, Visual Studies Workshop Press, 1985.

5

Debroise Olivier and Medina Cuauhtémoc (eds.), The Age of Discrepancies: Art and Visual Culture 1968–1997, Mexico City, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2007, pp. 155-159.

6

Email correspondence with Magali Lara, 8 February 2019. Literature has long played a crucial role in Lara’s work, particularly the writing of Margaret Atwood, E. E. Cummings and Leonard Cohen.

7

Email correspondence with Magali Lara, 4 January 2019.

8

All translations are by the author unless otherwise noted.

9

Giunta Andrea, “Feminist Disruptions in Mexican Art, 1975–1987”, Artelogie 5, October 2013.

10

Although women belonged to many of Los Grupos, they were few and often overshadowed by their male colleagues. M. Lara herself formed part of the group Março, which she founded alongside artists Alejandro Olmedo, Gilda Castillo, Manuel Marín, Mauricio Guerrero, and Sebastían in 1979. Online: http://cral.in2p3.fr/artelogie/spip.php?article271

11

Barratt Martha, “Autobiography, Time, and Documentation”, p. 283.

12

In addition to artists’ books, experimental exhibitions, performance and theatre all became methods to establish alternative forms of narrative building that circulated beyond the boundaries of the institution, and ultimately prefaced the establishment of the first feminist art archive in Mexico.

13

M. Lara also collaborated on numerous mail art projects with the Argentine artist Edgardo Antonio Vigo.

14

For further investigation into international mail art networks, see: Gilbert Zanna, “Networking Regionalism: Long-Distance Performativity In The International Mail Art Network”, Tarea, vol. 4 no. 4, 2017, pp. 84-96.

15

Other artists and cultural figures in Mexico to consider in this context are Maris Bustamante, Lourdes Grobet, Rowena Morales, Yani Pecanins, Jesusa Rodríguez, and Carla Stellweg.

Madeline Murphy Turner, "The Archival Impulse: Magali Lara and Carmen Boullosa’s Collaborative Artists’ Books." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/pulsion-darchivage-les-livres-dartiste-collaboratifs-de-magali-lara-et-carmen-boullosa/. Accessed 1 July 2025