Polvo de Gallina Negra

Cordero Reiman, Karen, Mónica Mayer: sí tiene dudas… pregunte: una exposición retrocolectiva, Mexico City, MUAC – Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2016

→Mayer, Mónica, “¡Madres!” in The M Word. Real Mothers in Contemporary Art, edited by Myrel Chernick and Jennie Klein, Bradford, Demeter, 2011

→Barbosa Sánchez, Araceli, Arte feminista en los ochenta en México. Una perspectiva de género, México City, Casa Juan Pablos; Cuernavaca, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, 2008

Polvo de Gallina Negra. Mal de ojo y otras recetas femenistas, Centro Nacional de Arte Contemporano, Chile, January–April 2022

→¡Madres! Madre por un día, television program Nuestro mundo, August 1987

→Carta a mi madre, Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil, Mexico City, October–November 1987

→Las mujeres artistas mexicanas o Se solicita esposa, serie of 35 conferences in 35 diferent sites, Mexico, 1984

Mexican feminist art collective.

Polvo de Gallina Negra, founded in 1983, was the first self-described feminist art collective in Mexico. Over the course of a decade the group created a number of innovative public and participatory works involving performance and media interventions that disrupted patriarchal systems and attempted to transform conditions for women in art and society. Artists Mónica Mayer (b. 1954) and Maris Bustamante (b. 1949) met at the exhibition, Salon 77/78: Nuevas tendencias (Museo de Arte Moderno), where M. Mayer exhibited her now widely recognized work El Tendedero [The clothesline]. She had been involved in the women’s movement and spent two years studying feminist art practice at the Feminist Studio Workshop (Los Angeles,) while M. Bustamante was a founding member of the experimental and highly politically engaged art collective No Grupo (1977-1983). The group originally included photographer Herminia Dosal (1945-), however, she left after their first public performance.

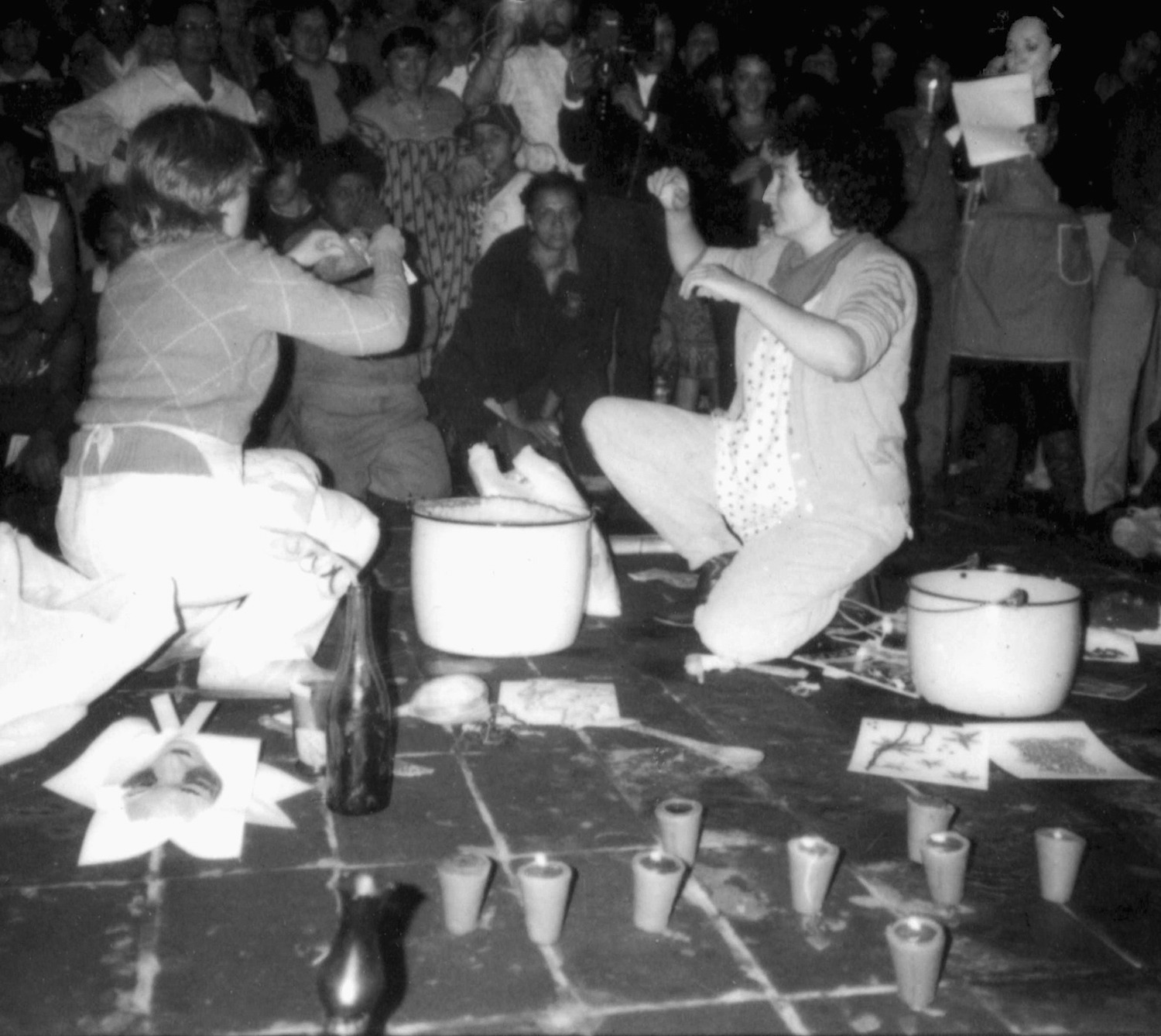

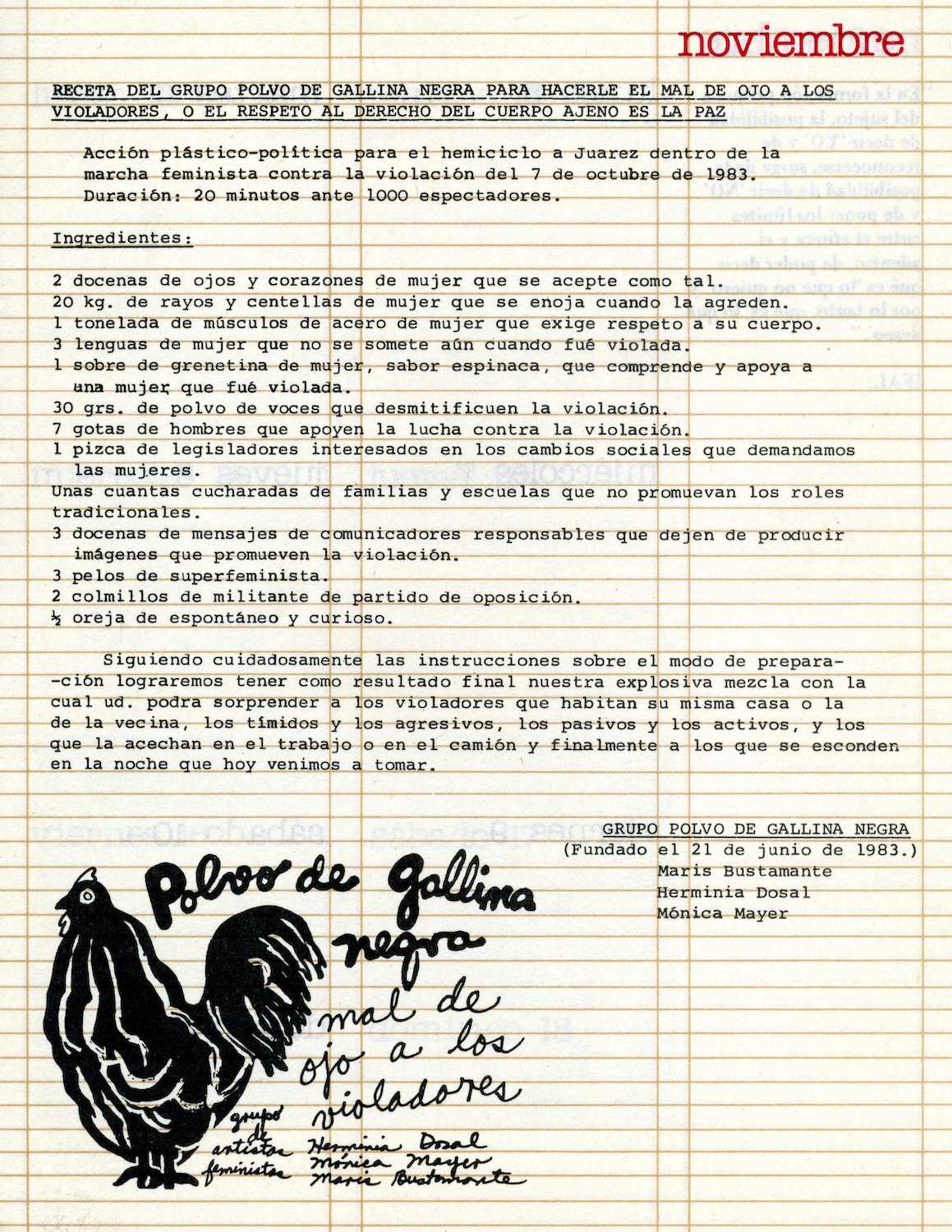

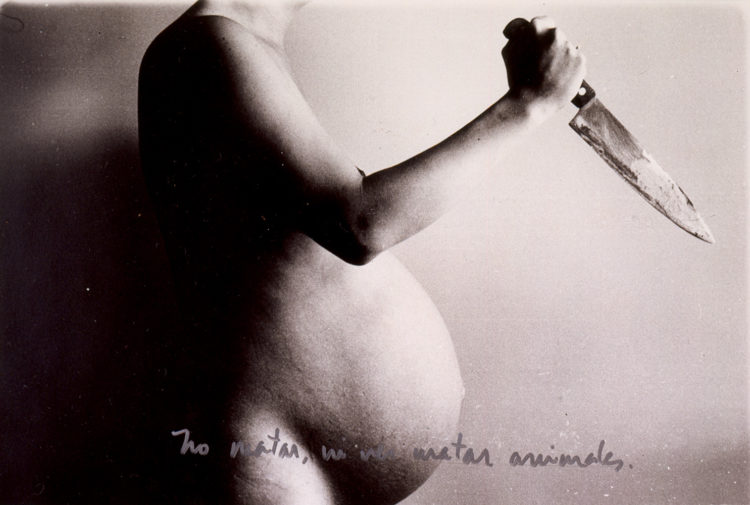

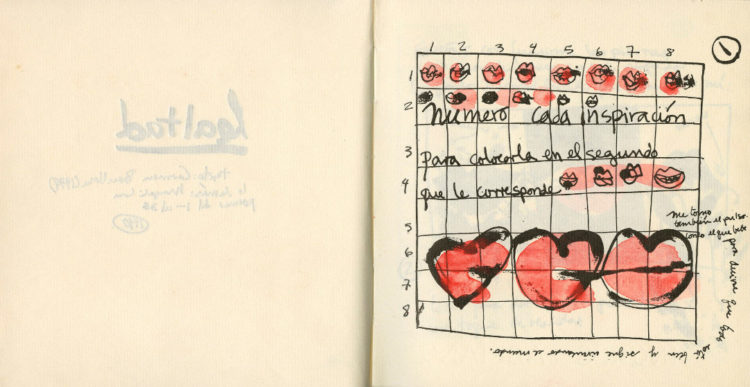

The name Polvo de Gallina Negra translates to “black hen powder”, a traditional remedy used as protection against the evil eye, which the artists anticipated they would receive in relation to the feminist content of their work. The group outlined three key goals they wished to achieve: “(1) To analyse women’s images in art and in the media, (2) to study and to promote the participation of women in art, and (3) to create images based on our experience as women in a patriarchal system, with a feminist perspective and with the goal of transforming the visual world in order to alter reality.” In their first performative event, titled EL RESPETO AL DERECHO AL CUERPO AJENO ES LA PAZ (respect for the right to the body of others is peace, 1983) held during a demonstration against violence against women in Mexico City, they prepared a potion which would cast the evil eye on rapists. Soon after they embarked on a tour of lecture-performances, titled MUJERES ARTISTAS O SE SOLICITA ESPOSA [Women artists or wife requested], at over thirty institutions around Mexico in 1984. These performances sparked heated debates with participants on pertinent feminist issues using the work of modern and contemporary women artists to generate these conversations.

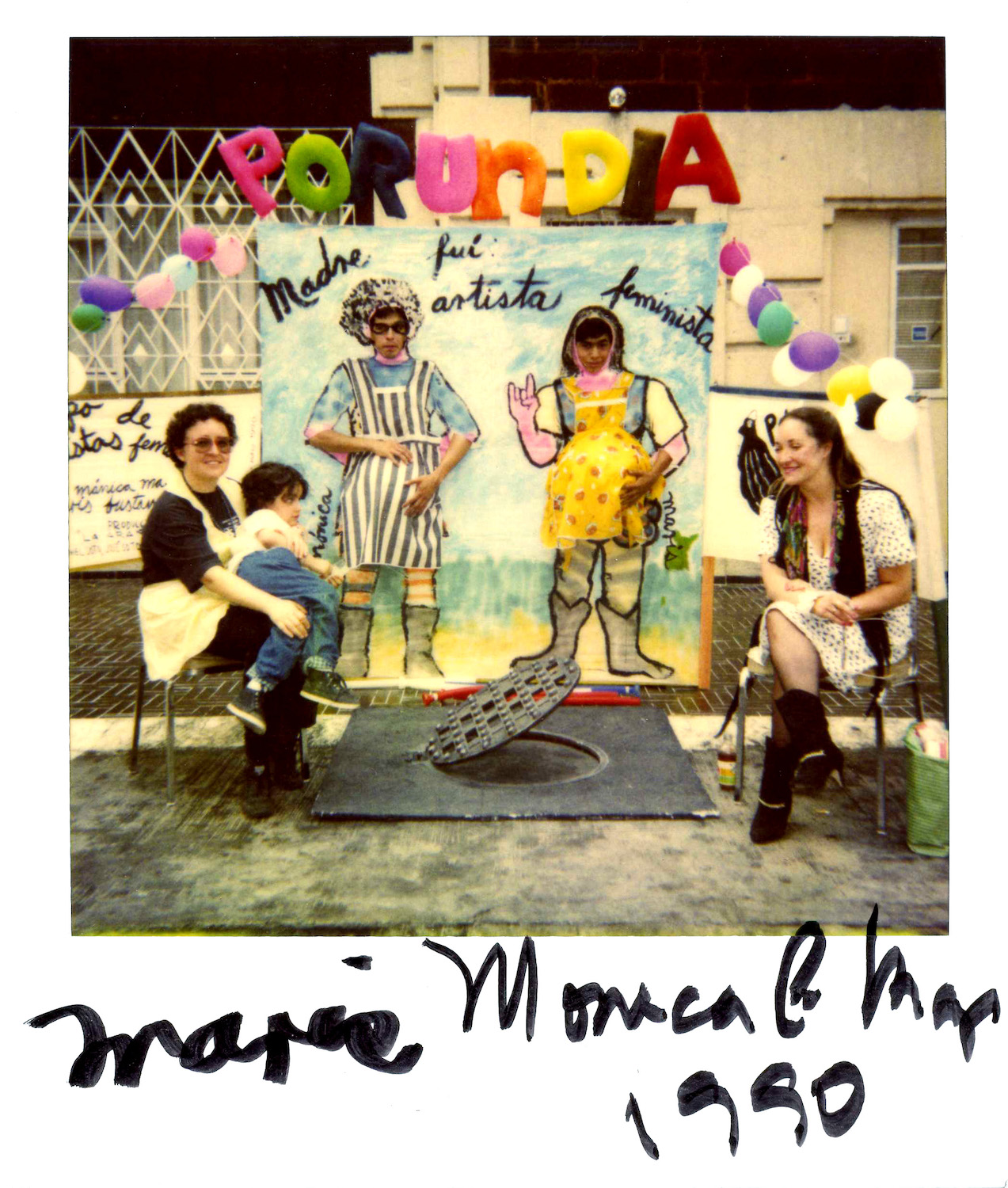

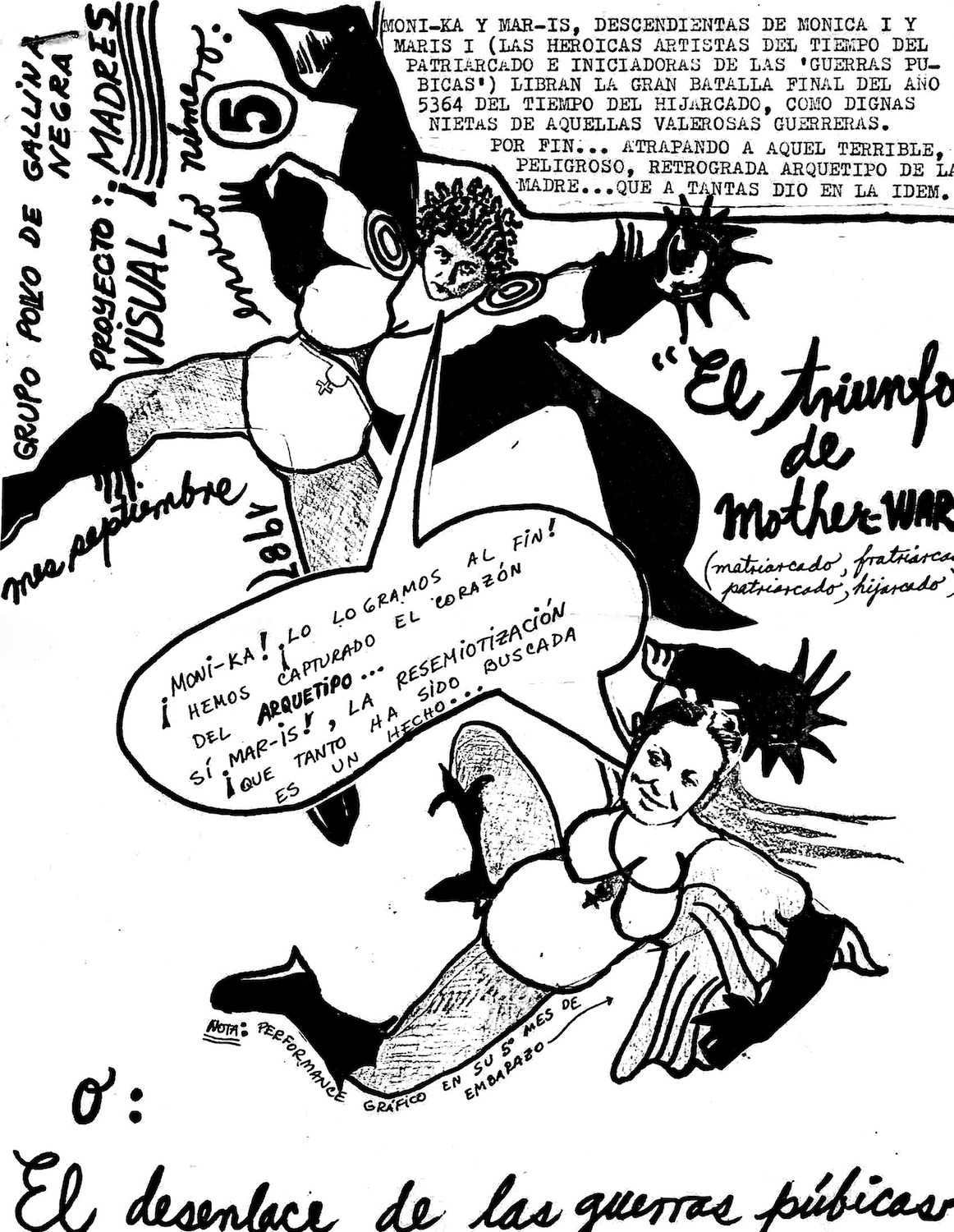

Their most widely known project, titled ¡MADRES! [Mothers!], spanned the years 1983 to1990, and consisted of multifaceted artistic interventions centred on the topic of motherhood in Mexican society. They connected with a broad audience, both in the streets and on television, using their own experiences as mothers and characteristic form of humour. In Madre por un día [Mother for a day, 1987] they appeared on the popular television program Nuestro mundo to discuss feminist art and stereotypes of motherhood, dressing up the host Guillermo Ochoa as a pregnant mother for their discussion. They used this highly visible performance, seen by roughly 200 million viewers, to promote a participatory companion exhibition at el Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil (Mexico City), Carta a mi madre (1987). They continued to engage the topic of motherhood and feminism in various performances held at educational institutions, museums, and public demonstrations in Mexico City until they disbanded in 1993 to pursue other projects. Their influence can be seen in the work of a new generation of feminist artists working in Mexico today.

A notice produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2022

Polvo de Gallina Negra, Madre por un día

Polvo de Gallina Negra, Madre por un día