Research

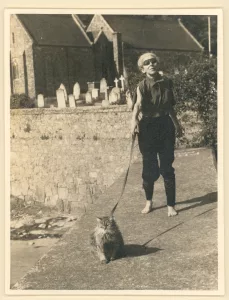

Claude Cahun, Le Chemin des chats V [The Way of Cats V], c. 1948, monochrome print, 20.9 x 16 cm, Jersey Heritage Collection

“Today, so I can fully savour the scent of your kisses, let your silk handkerchief be a blindfold over my eyes.”1 This is a line from Cigarettes (1918), an early Symbolist text by the artist and writer Claude Cahun (1894–1954) (who was at that time using an earlier alliterative chosen name, Daniel Douglas, after Oscar Wilde’s very bad gay boyfriend Lord Arthur Douglas).2 An emphasis on the erotics of darkness, veils, mist and occluded vision can be traced throughout Cahun’s oeuvre. Views and Visions, for instance, was first published in 1914 (when Cahun was a nineteen-year-old writing under another alliterative pseudonym, Claude Courlis) and, like much of what would come later, the text is shot through with views and visions that are shifty, unstable, partial, blurry, shadowy, glitchy and pleasurably obscured.

Claude Cahun, Le Chemin des chats V [The Way of Cats V], c. 1948, monochrome print, 20.9 x 16 cm, Jersey Heritage Collection

At a recent event at AWARE in Paris, I looked at The Way of Cats (c. 1948), a late photographic series by Cahun and their partner and artistic collaborator Marcel Moore.3 In this series, Cahun follows in the footsteps of their cat Nike, who is on a leash, leading the way.4 Paying particular attention to the fact that Cahun appears in these photographs walking barefoot while wearing a blindfold, I tried to trace the artists’ sustained emphasis on (a feline sense of) haptics and the pleasures of interdependency, against the dominant values of ocularcentrism (a word that refers to the privileging of vision over the other senses within Western epistemologies, especially when vision is embraced as the sense closest to the ideals of objectivity and detached reason).

Claude Cahun, Object, 1936, wood and paint with tennis ball, hair, and found objects, 13.7 x 10.7 x 16 cm © Art Institute of Chicago / Through prior gift of Mrs. Gilbert W. Chapman / Bridgeman Images

In this text, I want to continue that inquiry while looking to a small sculptural assemblage by Cahun, which is held at The Art Institute of Chicago with the posthumously granted title Object. First exhibited in the Surrealist Exhibition of Objects in Paris in 1936, Object shows a strained, bloodshot eye, wide open and staring straight ahead. The eye is painted on a tennis ball and elevated on a tiny stand, as a disembodied organ of vision isolated from the rest of the body, floating up in the sky amongst the clouds.

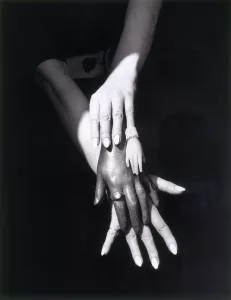

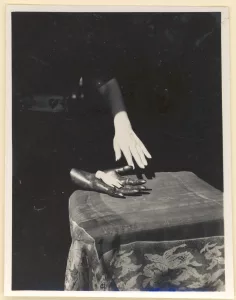

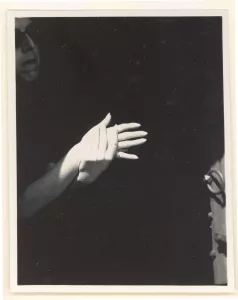

To counter the misguided fantasy of the eyeball’s elevated disconnection, Cahun has added some correctives. First, the little doll’s hand, which has been ushered onto the scene to accompany the lofty organ of vision with the possibility of fingery touch. Hands are a recurring motif in Cahun and Moore’s work, as demonstrated in the selection of images published with this text. In the Object assemblage, the hand can be read as a reminder not to let optics become disconnected from haptics. There’s also the pubic hair that Cahun has glued around the top of the eye, inviting it to become an optical organ that is also a sexual organ. It’s erected upright with possibly phallic verticality, but the eye shape is also turned on its side, appearing adamantly vulvic. The addition of pubic hair (Cahun’s own?) emphasises the eye’s (ambiguously or multiply gendered) genital potential.

Through a gathering of fragmentary parts, Object proposes a reconfigured sense of embodiment that is optic and haptic and sexual, all at once. Questions we might ask in its company include: Who is served when the function of the eye is separated out from the rest of the body? What happens when (what Donna Haraway has theorised as) the transcendental “view from above” is pulled down into unmediated, down-and-dirty tactility?5 How can the “uses of the erotic” (Audre Lorde’s term) disrupt ocularcentrism?6 What would it mean to perceive the world through the sexual organs? To “see it feelingly” (Shakespeare’s term)? To sense with (what the theorist of trans animalities Eva Hayward calls) “fingeryeyes”?7

Claude Cahun, Untitled (Hands), c. 1936, developed gelatin silver print, 25.3 x 19.8 cm, Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Jacques Faujour/Dist. GrandPalaisRmn

Claude Cahun, Untitled (Hands and Table), monochrome print, 1936, 11 x 8 cm, Jersey Heritage Collection

Claude Cahun, Hands, c. 1936, monochrome print, Jersey Heritage Collection

Claude Cahun, La Main sèche [The Dry Hand], 1939, monochrome negative, 115 x 85 mm, Jersey Heritage Collection

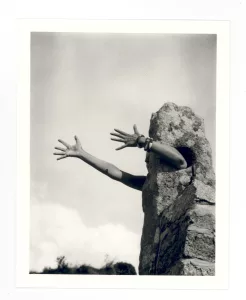

Claude Cahun, Je tends les bras [I Reach Out], 1932, monochrome negative, 115 x 85 mm, Jersey Heritage Collection

Coinciding with the Surrealist Exhibition of Objects was an issue of Cahiers d’Art journal on the theme of “the object”. Cahun’s contribution to this issue, an essay titled Beware Domestic Objects, argues that mundane, everyday objects have latent, strange, non-utilitarian, irrational, unknown and potentially liberatory powers and animacies that we need to get in touch with. Touch is key; these potentialities of domestic objects must be tapped into experientially rather than conceptually. Cahun insists that we can’t just read about them or stand back and look at them from a reasonable, detached distance (like an eyeball floating in the sky). In their words, “I could go on and on about those objects: they will speak to you better themselves, and they would speak still better if we could touch them in the dark.”8

Besides touching objects in the dark, Cahun also wants us to use our hands to “manipulate, tame [and] construct” our own irrational objects.9 The word “manipulate”, in this translation, comes from the French manier, which could also be translated as “handle”. All these words relate to hands: handle, manier, manipulate, la main. In the next sentence of the essay, Cahun turns to another hand-related term (in both French and English): manual. “In certain respects,” they write, “manual labourers may be in a better position than intellectuals to understand [irrational objects], were it not for the fact that the whole of capitalist society – communist propaganda included – diverts them from doing so.”10

Bourgeois intellectuals who (like Cahun) do not have to get their hands dirty with manual labour are usually (like the disembodied eyeball in Object), too far up in the clouds of conceptualism to be able to understand – intimately and tactically – the anti-instrumentalist, non-rationalist, unmediated animacies of objects. At the same time, those who are forced to live the drudgery of manual labour, day in and day out, are also usually prevented from “touching objects in the dark” and grasping their irrational and potentially liberatory forces, because capitalism necessarily alienates manual workers from the products of their labour.

Or at least this was Cahun’s concern, writing in the French capital in the mid-1930s. Their inclusion of “communist propaganda” as a part of “capitalist society”, in the above passage, is a deliberate provocation. They were engaged with various leftist revolutionary groups, but they grew increasingly wary of the Stalinist order that said the role of the revolutionary artist was to produce directly legible communist propaganda in the form of Socialist Realism. Their pamphlet Les Paris sont ouverts (1934) – initially written as an address to their comrades in the Association for Revolutionary Writers and Artists (AEAR) in 1933 – outlines a defence of Surrealist, avant-garde aesthetics and the possibilities of what they called “indirect action”.

Rather than thinking about revolutionary art only as something that follows predetermined criteria for consciously declared revolutionary content, Cahun argues for a revolutionary art that could remain mysterious and unruly, with potential effects moving through the world beyond the artist’s direct knowledge or intentions. Refusing the demand that artists produce instructive propaganda, Cahun insists that the political potency of a poem or artwork can lie in wait as an unseen, latent force that might be activated at an unknown later date. At the same time, they point out, a work that is directly declared as revolutionary at the outset can “cease to be revolutionary, or even become counter-revolutionary”, in a different context.11 Here, they give the example of La Marseillaise, which started as a revolutionary chant and later became neutralised as the French national anthem.

The (rather cryptic) inscription on the yellow base of the Object assemblage relates back to this point: “La Marseillaise is a revolutionary song / The law punishes counterfeiters with forced labour”. In 1935 (the year between Cahun’s 1934 pamphlet and the 1936 Object), Jacques Duclos, a leader of the French Communist Party (PCF), declared at a rally consecrating the Popular Front that “La Marseillaise is a revolutionary song”.12 As a part of the short-lived (anti-Stalinist) communist and anti-fascist revolutionary group Contre-Attaque, Cahun was critical of what they saw as the PCF’s reformist politics in the turn to Popular-Frontism. From their perspective, the embrace of national symbols (like La Marseillaise) amounted to an abandonment of socialist internationalism and the aim of revolution. Addressing a Contre-Attaque meeting in 1936, Cahun emphasised their staunch anti-nationalism, insisting that those “fanaticised by patriotism, even if it is the so-called proletarian patriotism”, will “sooner or later become the puppets of the imperialists”.13

The 1930s are famous for infighting and political break-ups within leftist movements. In Cahun’s case, their dissatisfaction with the trajectory of the PCF stemmed from the fact that they wanted an anti-capitalist, anti-fascist politics that was also anti-nationalist and – against the Stalinist mandate for Socialist Realist aesthetics – anti-rationalist. I am attempting to write about all of this in more detail elsewhere; for now, I will end by connecting back to the critique of ocularcentrism that can be traced in Cahun’s art and writings. Bound up with this critique was an insistence on the multi-sensory knowledges of the flesh. Beyond instrumentalist, disembodied optics, and beyond rationalist formulas for communist propaganda, Cahun’s work opens towards the possibilities of an unreasonable liberatory praxis that nurtures strangeness, contradiction, messiness, illegibility, queerness and enfleshed disobedience.

Looking back on the 1930s later in life, in an unfinished memoir, they reflected, “discursive rationalism was the chosen terrain of the young ‘revolutionary’ gang, a terrain that was hardly mine […] I tried to explain to the ‘Marxists’: I am living flesh, indivisible, and resistant to liberation through dictatorship”.14

Daniel Douglas, “Cigarettes”, La Gerbe, No. 3 (1918): 62–63; 63.

2

For more on the influence of Oscar Wilde on Claude Cahun see Lizzie Thynne, “‘Surely You Are Not Claiming to Be More Homosexual than I?’ Claude Cahun and Oscar Wilde” in Oscar Wilde and Modern Culture: The Making of a Legend, ed. Joseph Bristow (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2008), 180–208. For more on Lord Arthur Douglas as a bad gay see Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller, Bad Gays: A Homosexual History (London and New York: Verso, 2022).

3

Amelia Groom and Juliet Jacques, Myself (For want of anything better), AWARE, Paris, 10 March 2025). Recording published by AWARE 2 April 2025. YouTube video, 1:16:44. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1w63zogTg-k&ab

4

The series of eight undated photographs is held in the Claude Cahun collection at Jersey Heritage. Each image in the series, entitled Le chemin des chats, is accompanied by a short poetic text by Cahun. The couple made another series of photographs showing Cahun being taken on a walk by a cat on a leash in 1953.

5

Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective”, Feminist Studies, Vol. 14, No. 3. (1988): 575–599.

6

Audre Lorde, “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audre Lorde (Berkeley: Crossing Press, 2007) 53-59.

7

Eva Hayward, “FINGERYEYES: Impressions of Cup Corals”, Cultural Anthropology, Vol. 25, Issue 4 (2010): 577–599.

8

Claude Cahun, Beware Domestic Objects! trans. Guy Ducornet, in Surrealist Women: An Introduction ed. Penelope Rosemont (London: The Athlone Press, 1998): 59–61; 60.

9

Ibid.

10

Ibid.

11

Claude Cahun, Les Paris sont ouverts (Paris: Le rayon blanc, 2025): 33.

12

Steven Harris, “Coup d’œil”, Oxford Art Journal, Vol. 24, No. 1 (2001): 89–111; 107.

13

Claude Cahun, “RÉUNION DE CONTRE-ATTAQUE DU 9 AVRIL 1936”, in Claude Cahun: Écrits, ed. François Leperlier (Paris: Jean-Michel Place: 2002) 563–564; 563.

14

Claude Cahun, “Confidences au miroir”, in Claude Cahun: Écrits, 573–626; 578–579.

Amelia Groom is a writer and art historian who was the recipient of the 2025 AWARE (Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions) residency programme for research on women and non-binary photographers and video artists, hosted at the Villa Vassilieff in Paris. Groom recently wrote the introduction for a new edition of Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore’s 1930 artist book Aveux non Avenus (Cancelled Confessions, Siglio Press, 2025), and is working on a book-length study that reads Cahun and Moore’s art, antifascist activism and political theories through the lenses of queer and trans ecologies.

Amelia Groom, "Touching Objects in the Dark with Claude Cahun." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/toucher-les-objets-dans-lobscurite-avec-claude-cahun/. Accessed 11 February 2026