Research

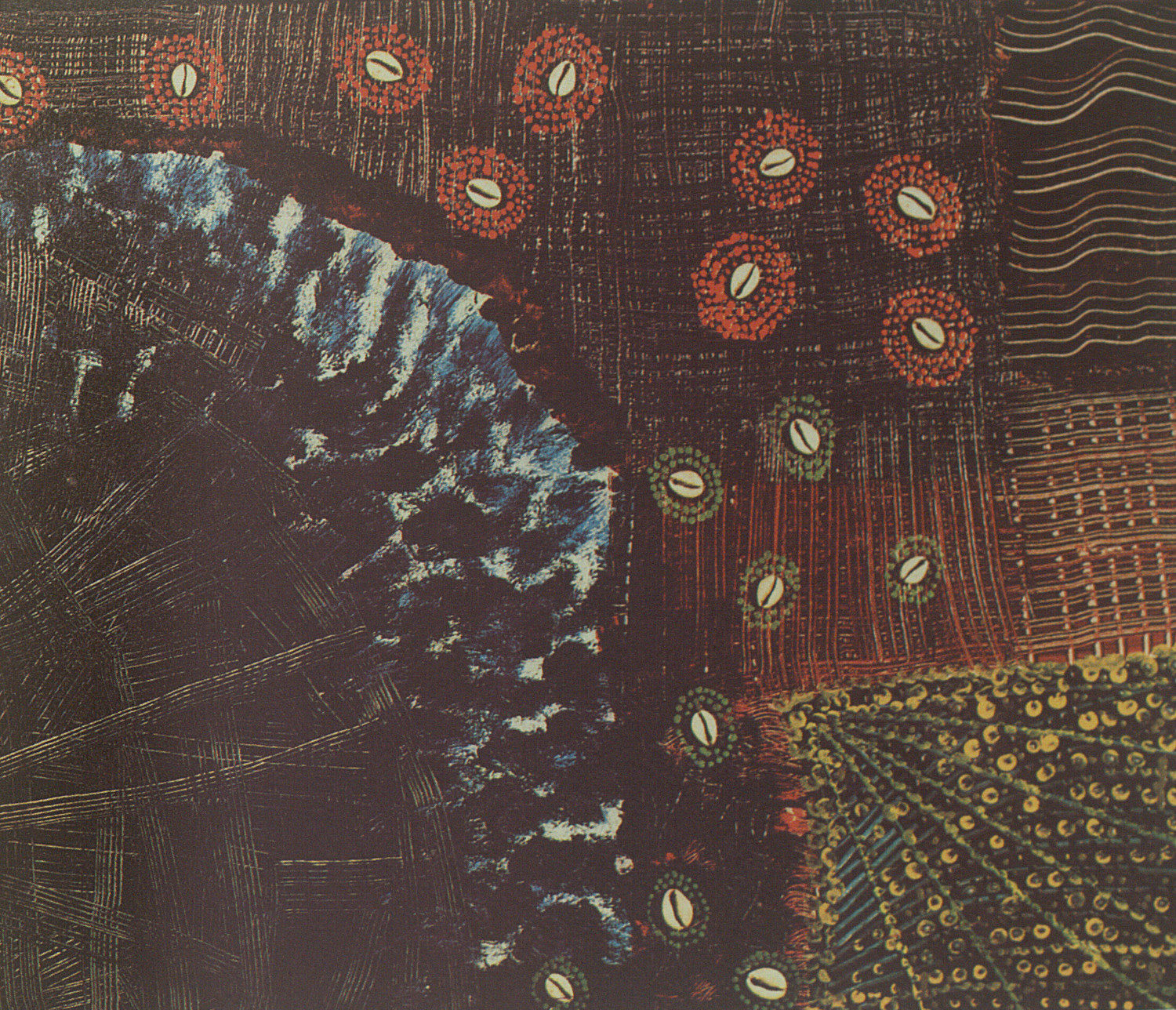

Younousse Seye, La Danse des cauris, 1974, oil on canvas and cowrie collage, 74 x 61 cm, © Photo: Éditions musées nationaux

Among the first generation of artists in Senegal following the country’s independence from France in 1960, Younousse Seye (born in 1940) plays a particular role. She is one of the artists who were close to the poet, philosopher, and first Senegalese president Léopold Sédar Senghor, and who actively engaged with his ambitious cultural policy. At the same time, as a self-taught artist and the only woman participating in the early exhibitions of the so-called “école de Dakar”, Y. Seye maintained a critical distance towards the state-sponsored art scene.

Since the late 1960s, she has taken a stance on issues of art and society in interviews published in newspapers and magazines. In a conversation with the author in Dakar in June 2018, the artist, now 78 years old, talks about the beginnings of her artistic career in the 1960s and 1970s, and about the political and social role of contemporary art in post-independence Senegal and Africa.

Younousse Seye, Contestation, reconstituted marble paint, 130 x 160 cm, © Photo: Judith Rottenburg

Younousse Seye, Contestation (detail), reconstituted marble paint, 160 x 130 cm, © Photo: Judith Rottenburg

In the entrance of Y. Seye’s house in Dakar, a work from 1980 entitled La Contestation [The Contestation] is leaning against a wall. It is made out of reconstituted marble, a material the artist uses due to its durability for artworks on buildings and in public space. The surface is crossed by dynamic lines she has drawn into the still damp material. In the upper half of the image, eight faces turned to the left become apparent, in the lower half five faces look straight out at the viewer. Running across the middle section of the image, an inscription of the word “Apartheid” can be made out, the last few letters of which are superimposed. The colours of the painting – green, yellow, red and black –, often used as Pan-African colours, correspond to those of many African national flags, including that of Senegal, which after independence were designed following the model of the Ethiopian flag. The faces in the painting are characterised by wide-open eyes and mouths, depicted as geometric shapes. “The mouth is the symbol of speech, of expression, of contestation”1, the artist comments. “When you are not satisfied in society, you express yourself.” With this work she says to have created “a form that is able to express anger, the anger of mankind, the anger of society.”

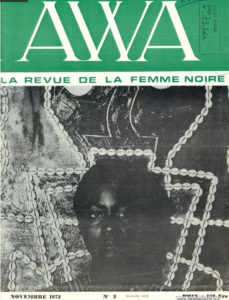

The social and political role of art is central to Y. Seye’s artistic practice. In an interview with the Ivorian newspaper Fraternité Matin in 1972, where she is introduced as the “first African woman painter”, she states: “For me, painting is a means of expressing myself, a means of engaging in a dialogue with society, a means of communication and communion, because the role of the artist is very important in society.”2 In a large solo exhibition in the foyer of the Théâtre national Daniel Sorano in Dakar in 1977, the artist provides a clear demonstration of her political commitment. In the 107 paintings on display, she addresses among other things the subject of apartheid, and questions African solidarity. In an interview with the women’s magazine Amina, she declares on this occasion: “All of us, writers, poets, painters, etc., are committed to the African cause. There is no alternative. We are here to denounce the tragedies of society, we are an alarm signal.”3 Y. Seye often uses the attention that is paid to her as an artist in order to express political concerns and to address the position of women in society. In 1972 she poses in front of one of her paintings for the cover of the November issue of Awa. La revue de la femme noire, and explains in an interview: “I believe in the evolution of women and their participation in the future of this continent. […] I would like us women to participate effectively in everything that is happening in our countries. […] It is not enough to proclaim it, we must put it into practice and try to bring a kind of homogeneity to our society.”4

Painter Younousse Seye in front of her paintings « Carcan », front Cover of Awa : la revue de la femme noire, November 1972, no. 2

The fact that Y. Seye succeeded in maintaining an independent, critical voice within the state-sponsored art scene while at the same time positioning herself at the heart of it, can partly be explained through her unusual career path within this context. Unlike most of her fellow artists, Y. Seye did not attend the École des arts du Sénégal that was the institution at the centre of artistic production in Senegal in the 1960s. The only woman to participate in the exhibitions of the country remained a self-taught artist. Y. Seye says that it was above all her mother who had influenced her artistic practice. From an early age on, she had assisted her mother who worked as a fabric dyer in Saint-Louis. “She taught me that you have to look at the colour of the sky, the blue gradient, that you have to […] compose with your environment.” Having cloth dyeing as a starting point, Y. Seye began as a teenager to produce canvases and to paint them. “Growing up, I had a different vision of the world. There is a distinction between batik work, which is technical, and the work of a painter, who looks for material.”

When it was time for Y. Seye to choose a career, she decided to do an apprenticeship as a shorthand typist. She married, moved to Dakar, started a family, and worked as a shorthand secretary. While her artistic work was still unknown to the public, she made a name for herself as an actress. Ousmane Sembène, who won a prize at the First World Festival of Black Arts in Dakar in 1966 as well as the Prix Jean Vigo for his film La Noire de …, offered her a role in his new film Mandabi, his first film in Wolof. This marked the beginning of a collaboration that continued in the films Xala (1976) and Faat-Kiné (2000). Mandabi won the International Critics’ Prize at the 1968 Venice Film Festival. When journalists came to Y. Seye’s house to interview the actress, her artistic work attracted their attention and they reported on it. L. S. Senghor thereupon offered her the opportunity to study at the École des arts du Sénégal where she would have been the first woman student. But Y. Seye as a working wife and mother felt obliged to reject this offer: “I couldn’t go back to the arts institute to do a course and study, I didn’t have time any more. I had my children, I had my job. […] On top of which I took care of the house, of my husband […]. We laughed and then I went on with my life.”

L. S. Senghor became one of the artist’s most important interlocutors. They shared the view that visual arts could make an important contribution to nation building and to the creation of an independent Africa. Y. Seye found interest in the cultural emancipation movement of Négritude, which L. S. Senghor had co-founded in Paris in the 1930s and which inspired his cultural policy in Senegal. However, despite their close intellectual exchanges, the artist sees limitations in Senghor’s vision of contemporary Senegalese art and its state promotion: “[…] the president talks about art, but he doesn’t practice art. And when you practice art, you can see the difference between speaking and doing.”

The Pan-African festivals of 1966 in Dakar, 1969 in Algiers, and 1977 in Lagos were key moments for Y. Seye’s orientation and positioning as an artist. These large-scale cultural events brought together artists of all disciplines from Africa and the diaspora, presenting their work to an international audience. They allowed Y. Seye to build a network across the African continent and beyond. She remembers the First World Festival of Black Arts, which was hosted by the city of Dakar in 1966 for a month and attracted about 20,000 visitors, as a particularly formative experience: “It was amazing to gather so many personalities from the art world in one place, with music from everywhere. African culture vibrated in everything.” Still unknown as a visual artist at the time, Y. Seye worked as a hostess at this festival. She welcomed important guests at the airport, organized their meetings and appointments and started conversations with them. “I welcomed Emperor Haile Selassie, I welcomed Aimé Césaire, many people who came to the Festival. […] Aimé Césaire was amazed to meet all these people at the same time and witness the dynamics at work in our culture.” She attended with great interest the international conference that brought academics and artists together during several days to discuss historical and contemporary issues in African art. She enthusiastically followed the festival’s artistic manifestations – exhibitions, concerts, dance and theatre performances – which made her discover “not just Africa, but the world”. “For example, going to the Sorano theatre to see Alvin Ailey dance was something that none of us had seen before.” The Dakar festival has “reinforced [her] in the realizations of [her] art”.

Younousse Seye, Light Bearer, 1971, oil on canvas and collage of cowrie, 171 x 129 cm

Younousse Seye, Femme aux cauris, 1974, oil on canvas and cowrie collage, 148 x 78 cm, © Photo: Éditions musées nationaux

When three years later the Pan-African Cultural Festival took place in Algiers, Y. Seye was a well-known artist in Dakar. Alioune Sène, Senegal’s minister of culture at the time, invited her to take part in the exhibition of Senegalese artists. She experienced the festival in Algiers as less “dense” than the one in Dakar, but remembers the exhibition of the Senegalese artists as a particular success: “I was there with many cultural figures, and it was very crowded, the public came to see it, the public loved it.” Y. Seye presented an early painting on which she had attached cowrie shells, a characteristic element of her work until today, referencing the different meanings of cowrie shells in the history of Africa: as currency, as a symbol of fertility and femininity, and as they are used in West African masks. “It is a dynamic symbol that allows the artist who I am the presence of Africa in contemporary art.”

She will present two similar paintings with cowrie shells at the first exhibition of contemporary artists from Senegal in France which took place at the Grand Palais in Paris in 1974, as well as in an exhibition then traveling to different countries around the world.

For Y. Seye’s career as an artist, the exhibition in Algiers represented a breakthrough. According to Jean-Fernand Brierre, head of the department of culture in Senegal at the time, it established “the success of a woman who upsets all aesthetic norms”.5 With her painting in Algiers, she won a UNESCO prize, which granted her a travel and exhibition scholarship to a place of her choice. She did not opt for a European or American metropolis, but – following her interest in the arts and aesthetic practices of the African continent – for Korhogo in Ivory Coast. There, she investigated the use of cowrie shells in different areas of society and further developed her artistic work with them. In 1972, she presented the pieces produced during this stay at the Hôtel Ivoire in Abidjan.6

While Y. Seye through her entire career has developed an aesthetic that visually translates concepts such as Négritude, Africanity, or Pan-Africanism, she has maintained a critical distance to the political reality of the continent and the project of an African unity. In 1977, in her solo exhibition in Dakar, she presented among her paintings a blank, unsigned canvas entitled Solidarité africaine [African Solidarity] which she later commented by asking: “Who would sign a canvas on African solidarity?”7 When L. S. Senghor visited the exhibition in December 1977 together with Y. Seye, journalists did not only describe his surprise about the blank canvas and its title, but also reported the answer that Y. Seye had put forward with a mischievous smile: “For my part, I understand African solidarity as negative”, to which L. S. Senghor had in turn replied, “It’s a void.”8

Judith Rottenburg is a postdoctoral research fellow in the project “Developing Theatre: Building Expert Networks for Theatre in Emerging Countries after 1945”, supported by the European Research Council (ERC) at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich, where she is doing research on Pan-African festivals of the 1960s and 1970s. She completed her PhD dissertation on the history of painting and tapestry in Senegal in the first decades following the country’s independence. Her research explores entangled art histories and the circulation of ideas, objects, and people in the field of arts between Africa, Europe, and the Americas in the twentieth and twenty-first century.

Unless otherwise stated, the artist’s quotations in this text are taken from a conversation with the author on 3 June 2018 in Dakar.

The author would like to sincerely thank Younousse Seye for her generosity to share her stories, as well as Ibrahima Wane for putting her in touch with the artist.

2

“Première artiste-peintre africaine, Younousse Seye: ‘Le langage des génies se transmet dans le secret des cauris’…”, Fraternité-Matin, 11 July 1972, p. 8.

3

“Peintre engagée, Younousse Seye chante les joies et les peines de l’Afrique”, Amina, March 1978, no. 64, p. 3.

4

Erneville Annette d’, “Younousse peintre”, AWA. La revue de la femme noire, November 1972, no. 2, p. 24.

5

Quoted in Fall Youma, “De quelques femmes dans l’histoire de l’art au Sénégal”, in Dak’Art 2006. 7ème biennale de l’art africain contemporain, Dakar, Secrétariat général de la biennale de l’art africain contemporain de Dakar, 2006, p. 70.

6

Ibid., p. 74.

7

“Peintre engagée, Younousse Sèye chante les joies et les peines de l’Afrique”, Amina, March 1978.

8

Diedhiou Djib, “Senghor à l’exposition Younousse Seye: ‘Le génie est d’exprimer simplement des idées fortes’”, Le Soleil, 9 December 1977.

Judith Rottenburg, "Younousse Seye: The Making of a Pan-African Woman Artist in Post-Independence Senegal." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/younousse-seye-le-devenir-dune-artiste-panafricaine-dans-le-senegal-de-lapres-independance/. Accessed 16 July 2025