Okuhara Seiko

Wakamatsu, Yurika, “Painting in Between: Gender and Modernity in the Japanese Literati Art of Okuhara Seiko (1837–1913)”, PhD dissertation, Harvard University, 2016

→McClintock, Martha J., and Victoria Weston, “Okuhara Seiko: A Case of Funpon Training in Late Edo Literati Painting”, in Jordan, Brenda G. and Weston, Victoria (eds.), Copying the Master and Stealing His Secrets: Talent and Training in Japanese Painting, Honolulu, University of Hawai’i Press, 2003, 116–146

→Fister, Patricia, Japanese Women Artists 1600–1900, Lawrence, Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, 1988

The Three Perfections: Japanese Poetry, Calligraphy, and Painting from the Mary and Cheney Cowles Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 10 August 2024–3 August 2025

→Her Brush: Japanese Women Artists from the Fong-Johnstone Collection, Denver Art Museum, Denver, 13 November 2022–16 July 2023

→Okuhara Seiko Exhibition: Celebrating 100 Years Since the Artist’s Death [Botsugo hyaku shūnen kinen: Okuhara Seiko-ten], Kumagaya City Library, Kumagaya, 2 April–12 May 2013

Japanese literati painter, poet, and teacher.

Best known for their bold ink landscape painting style, the Japanese painter Okuhara Seiko was one of few women literati artists to receive a comparable level of popularity to their male counterparts during the Meiji period (1868–1912). Born as Ikeda Setsu, the fourth child of a samurai family in Koga Domain (modern-day Ibaraki Prefecture), Seiko first began to study painting with the painter Hirata Suiseki (1796–1863), himself a student of the eminent painter Tani Bunchō (1763–1841). Their early painting education under Suiseki involved frequently copying from Chinese masterworks of the Qing and Ming dynasties from copybooks, or funpon. In addition to painting, as a young person they were skilled in martial arts and scholarship – all traditionally masculine activities which predicated a lifetime of subversion of artistic and social gender expectations.

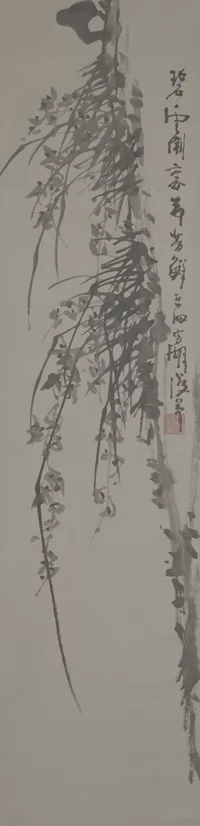

After studying in their hometown of Koga for eleven years, in 1865 Seiko relocated to the Shitaya area of Edo (modern-day Tokyo) to participate in the burgeoning Sinophile literati community there. Shortly after, in 1871, they also opened a school from their home, called “Pavilion of Ink Spitting Mist and Clouds” (Bokuto En’urō), where they taught painting and Chinese studies. The school was open to both male and female participants and had over 300 students at its peak. For Seiko to have so many followers, both as a woman and as a relatively young artist, was unprecedented. Their students and patrons came from all walks of life, including geisha, samurai, government officials and art critics. Their best-known student, the painter Watanabe Seiran (1855–1918), was a successful artist in her own right and remained with Seiko for more than forty years. The 1870s and 80s were the most prolific period of Seiko’s artistic career and works such as Orchids on a Cliff (1870–80s) illustrate the bold style of ink painting that they perfected during this time.

Seiko circumvented the standards for female artists of the time, cutting their hair short and often wearing men’s clothing, as well as omitting from their signature the customary –joshi character used by women painters. These choices, in combination with their lifelong proficiency in traditionally masculine activities, have led some contemporary scholars to describe them in gender neutral terms. While we do not know how Seiko would describe their gender identity today, this fluidity and subversion was core to both their artistic and personal life.

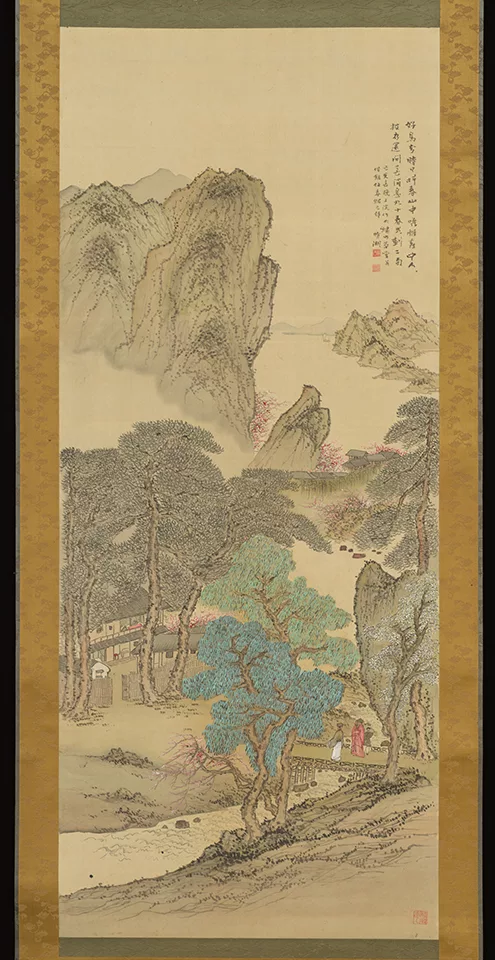

Following a period of declining popularity for literati painting in Tokyo and the political upheaval of the Meiji Restoration, in 1891 Seiko retired to the rural town of Kamikawakami, Saitama Prefecture. They continued to take commissions until 1912, when their health began to decline, and passed away a year later. Their later works from these years in Kamikawakami, such as Landscape in Blue and Green (1899), reflect a quieter and more colourful approach compared to their work made in earlier decades.

In collaboration with the Denver Art Museum as part of AMIS: AWARE Museum Initiative and Support

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2025