Fuku Akino

Akino, Fuku. Gamunshu: Bauru no uta [Collection of drawings and texts : Baul’s Song]. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo, 1992.

→Akino, Fuku. Nihonga wo kataru [About Nihonga Painting]. Osaka: Brain Center Inc., 1990.

AKINO Fuku: Commemorating the 100th Anniversary of the Artist’s Birth, The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, April 8–May 11, 2008; Akino Fuku Museum, Hamamatsu, June 7–July 27, 2008; The Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura & Hayama, August 9–October 5, 2008

→Fuku Akino: Trajectory of Creation, Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art, April 26–June 8, 2003; Tenshin Memorial Museum of Art, Ibaraki, July 19–August 31, 2003; Akino Fuku Museum, September 6–October 26, 2008

→INDIA Fuku Akino, Sagacho Exhibit Space, Tokyo, November 11–December 19, 1992

Japanese painter.

Fuku Akino was born into a family of Shinto priests at a shrine along the Tenryu River. She was taught to paint in the style of Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) and Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) by a drawing teacher at an ordinary elementary school, and received instruction in painting from an art teacher at the second division of a Women’s Normal School. Although she briefly became a teacher at an elementary school in her home neighbourhood, she found herself unable to give up her ambition to become a painter, and in 1927 she became a student of Rinkyō Ishii (1884–1930), a Japanese nihonga painter active at the government salon-style exhibition, and in 1929 of Suishō Nishiyama (1879–1958), also a Japanese nihonga painter. The following year, Akino exhibited her works at the exhibition of a private art school, Seikō-sha, in May and the government exhibition in October. Portrayed in the former are three young male apprentices enjoying a short break on their day off, dozing off from the fatigue of their usual daily routine as they are gently shaken by the movement of the train or being a little nervous about this rare outing. The latter work depicts a poor woman walking barefoot with the hem of her kimono drawn up in an undeveloped area on the outskirts of Kyoto, where cooking utensils have been discarded among the overgrown weeds. The following year, Akino’s work depicting an emaciated stray dog wandering in the wilderness under the blazing sun was passed over for the government exhibition. Both of these motifs were unusual for Japanese nihonga painting, but the distinctive characteristics of Akino, who had always been interested in people living at the bottom of society and wide, desolate expanses of land, were already apparent at this point.

In 1932, she married Kōjin Sawa (1905–1982), a senior student at the private art school, and their first son was born in January the following year. Due to her family’s financial situation, Akino chose typical motifs for her paintings that were to be exhibited at the government salon-style exhibition, where the decision over whether a painting would be selected or not was often directly related to its price. She showed paintings with familiar motifs at the exhibition of Seikō-sha in the spring and the government exhibition in the fall without fail. Examples of these works are On the Sand (1936, collection of the Kyoto City Museum of Art), which depicts herself and her three children resting by the Tenryu River in her hometown with shadows that were rarely seen in Japanese nihonga paintings at the time, and Red Clothes (1938, collection of the Kyoto City Museum of Art), a work in which Akino used variations of red paint to depict five young female models in five different poses around a square table, which won a special prize at the government exhibition and established her reputation as a young female painter.

In 1948, seeking a venue for her artistic activities in the new world following Japan’s defeat in World War II, Akino established Sōzō Bijutsu (renamed Sōga-kai in 1974 after the Nihonga Painting Division of the Shinseisaku Kyōkai) with like-minded mid-career Japanese painters from all across Japan. The works that she presented here were based on her own children, an ideal motif that allowed her to make them strike whatever poses she desired, repeatedly sketch them, and pursue deeper study and research at home. Highly acclaimed was Akino’s use of restrained, subtle colours and organic outlines, as well as her powerful depictions of groups of figures focused on how the forms of the bodies themselves that had not fully matured were articulated. In 1951, she was awarded the first Uemura Shōen Prize, given to a young female Japanese nihonga painter, for Boys in the Nude (1950, collection of the Akino Fuku Museum, Hamamatsu).

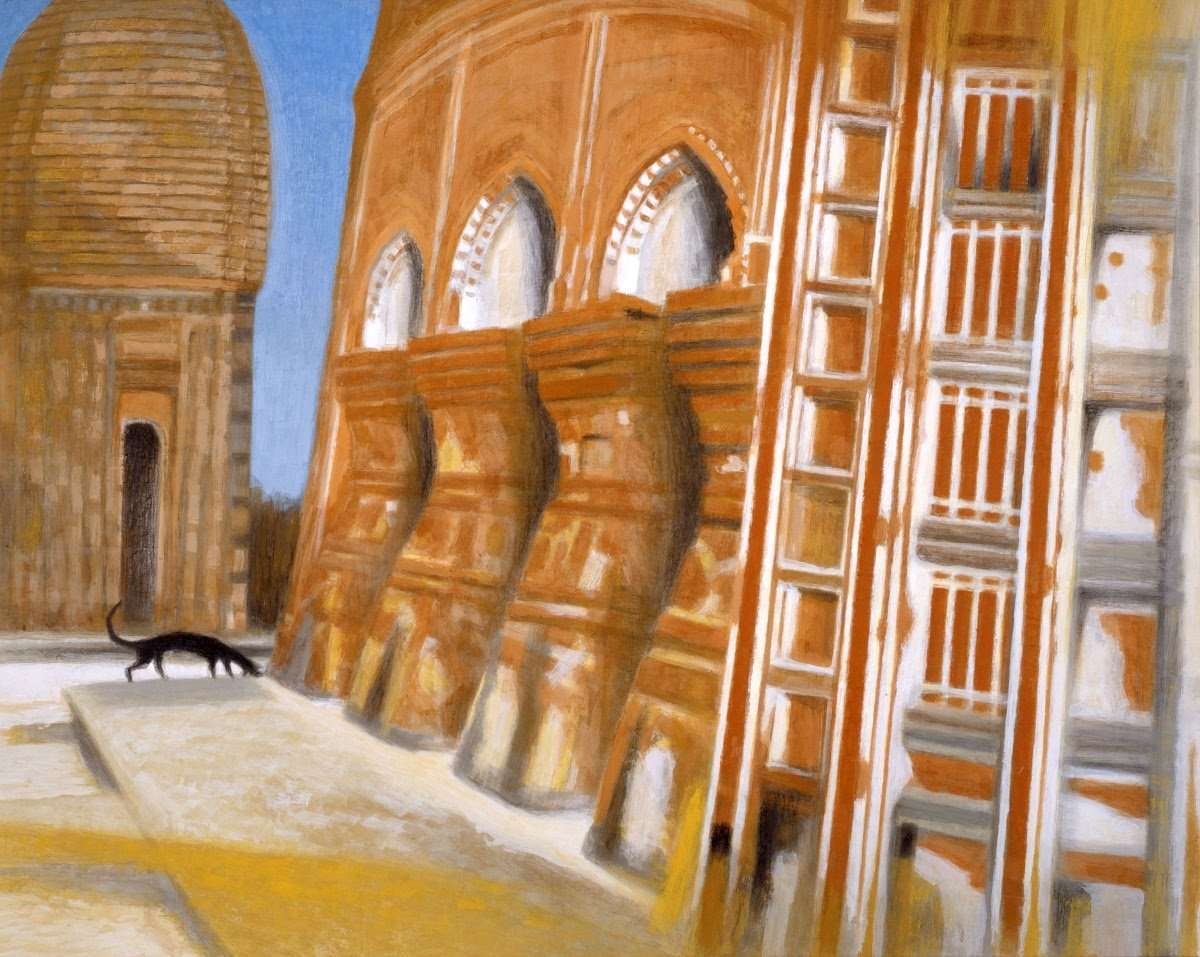

At a time when she was seeking new motifs for her paintings, depicting coastal landscapes, and teaching at Kyoto City University of Arts, Akino heard that an Indian university was looking for someone to teach Japanese nihonga painting, and went to Visva-Bharati University as a visiting professor for a year from July 1962. While teaching Japanese nihongapainting, she also toured the whole country and found herself enchanted by its majestic nature, and went on to make a total of twelve visits to India over her lifetime. Akino, who made the India series her lifework during the latter half of her life, initially painted magnificent landscapes such as Sunset over the Plain (1964, collection of the Kyoto City Museum of Art). Impressed by the people who laboured hard day after day with an unshakeable faith even in harsh environments, however, she gradually moved on to the landscape with auspicious patterns heartfeltly depicted by poor, illiterate women against landscapes, as seen in Prayer on the Earth (1983, collection of the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto), and paintings of temples, such as Terracotta Temple (1984, collection of the Akino Fuku Museum, Hamamatsu). In 1999, she was awarded the Order of Culture, but her vigorous enthusiasm for painting continued unabated. In 2000, she travelled to Africa on a study trip at the age of 92, and immediately presented the results at the Spring Sōga Exhibition the following year. Akino continued to work until the very end, passing away in October the same year.

A biography produced as part of the “Women Artists in Japan: 19th – 21st century” programme

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2023