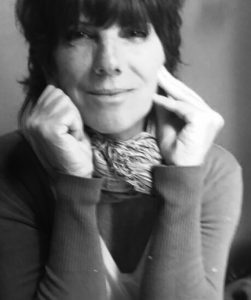

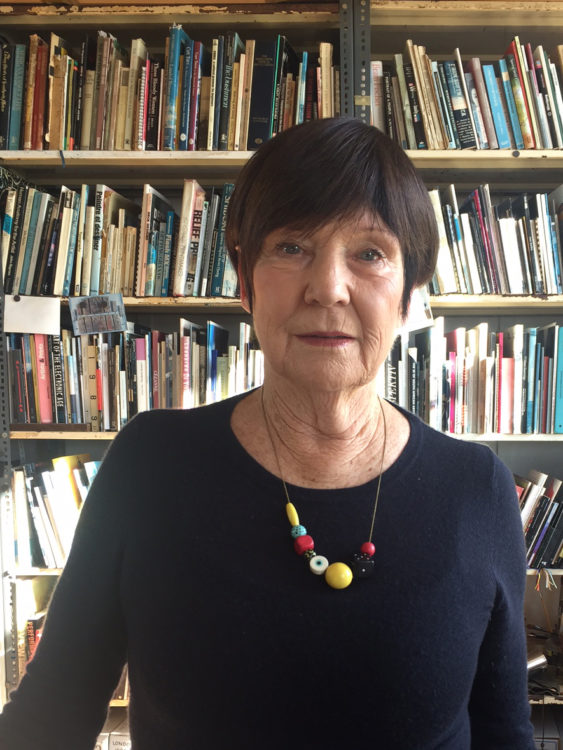

Ana Gallardo

Guarneri, María, “El pedimento 2009-2015”, in Venezia Art Magazine, Venice, 2015

→Baeza, Federico, “Escrituras de la vida cotidiana”, in caiana. Revista electrónica de Historia del Arte y Cultura Visual del Centro Argentino de Investigadores de Arte (CAIA), nº 2, 2013

Un lugar para vivir cuando seamos viejos, Parasol Unit Foundation for Contemporary Art, London, United Kingdom, 2012

→La hiedra, Galería Alberto Sendrós, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2006

→Material descartable, Juana de Arco, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1999

Argentine political visual artist.

Ana Gallardo defines herself as a political artist, saying that ever since she first thought of herself as a creative person she intended her practice to be one of resistance and transformation, with the belief that she could become a change-maker.

She is mainly self-taught, with no formal artistic training. Her mother was a painter and her father a poet – facts that lead her to contend that she inherited a certain notion about how to undertake artistic practices. She began painting in the late 1980s, joined the Grupo de la X and frequented various artists’ studios as part of her self-education. She identifies as a feminist – something she has discovered in the course of her artistic journey, making gender the subject of much of her production.

During the 1990s, she worked with the concept of domestic violence in her paintings. However, she has said that at that time art was dealing with other issues and consequently her work went largely unseen, causing her great frustration.

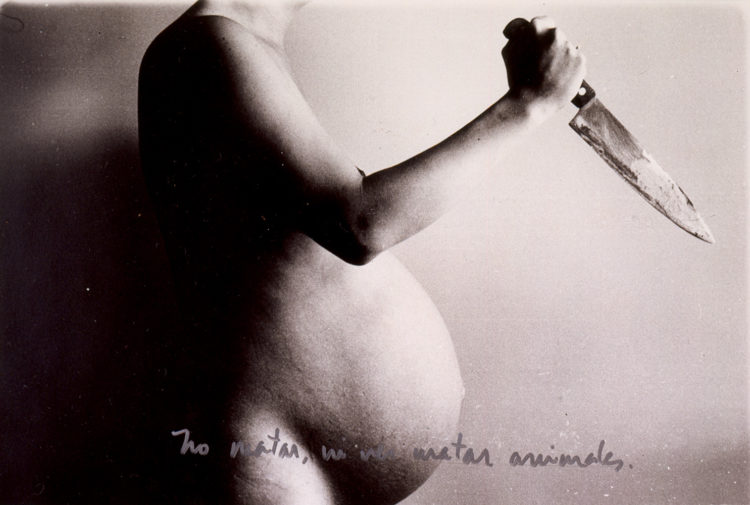

Although she started out as a painter, she gradually moved over to installations and performance – practices in which various media coexist. Her work interrogates various themes linked to gender. For instance, a series of her paintings from the 1990s represents methods of female contraception – a subject not as freely discussed as it is today. One is called Condón femenino [Female condom, 1995]. She also made three installations – Manifiesto escéptico [Sceptic manifesto, 1999), Material descartable [Disposable material, 2000] and Políticas corporales [Body politics, 2002] – about the question of abortion, which, because it was illegal in Argentina at that time, was carried out clandestinely with few, if any, safety precautions. Examining the problems inherent in this reality, she showed various items used for clandestine abortions, such as sprigs of parsley, sewing needles and many other objects ordinarily associated with the domestic sphere that in this context acquire another power, making visible things that are usually confined to private spaces. In La hiedra [The wound, 2006] she explored the life stories of five women with, as a common thread, their narratives about love – once again presenting things considered private and reaffirming the premise that the personal is political.

Another axis of her work is a critique of the elitist academic art system. Here we find pieces like CV Laboral [Curriculum Vitae, 2009], in which she recounts her work history, including jobs that have nothing to do with her creative practice but which were necessary for her to make a living.

Her latest projects, Escuela de envejecer [School for aging] and Un lugar para vivir cuando seamos viejos [A place to live when we’re old], which she has been working on since 2015, continue these critiques of gender relations and of the system, imagining a possible place where she would like to grow old. This is a project both artistic and sociological, since carrying it out involved research, interviews and work with people residing in homes for the elderly. A. Gallardo argues that a political artist is constantly seeking to change systems –either things that are wrong or that she finds uncomfortable – and that being an artist means being critical and always seeking to make change. She sees art as a tool to upend the established order; in short, this is what she is trying to do in all of her work.

A notice produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2021