Research

“The maternal body has a paradoxical status as both natural and exceptional, a sanctioned yet highly circumscribed form of female embodiment; like the nude, it is both a powerful cultural idea and a bodily state, but one which is unstable and open to multiple meanings.”1

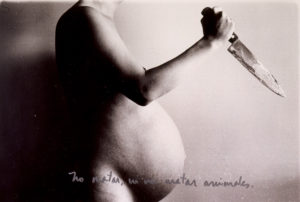

A naked woman is on the verge of stabbing her own pregnant womb. Her hand firmly holds a large knife pointing towards her swollen belly. Trembling with the shock of such a traumatic image, we can easily tell that the photograph captures a self-portrait of artist Marta María Pérez Bravo during her pregnancy.

As witnessed for example in the recent exhibition Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985 curated by Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and Andrea Giunta (Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; Brooklyn Museum, New York; Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo), a dystopian representation of pregnancy seems to emerge in the practice of several Latinx and Latin American women artists from the very end of the seventies onwards. Marta María Pérez Bravo (born in 1959), Johanna Hamann (1954–2017), Barbara Carrasco (born in 1957), and Josely Carvalho (born in 1942), among others, challenge the collective imaginary of maternity as blissful and cheerful, proposing instead a crude representation of the body. Free from the Catholic iconography that, from the fourteenth century onwards, has presented the pregnant woman in the guise of the “Madonna del Parto”, the female body in the work of these artists takes on novel, tragic, and creaturely qualities that portray maternity as an almost brutal phenomenon; this generates a dialectic of opposing but intertwined tropoi: the miracle of life against death, maternal love against violence.2

Aspects of motherhood have already been discussed by several scholars. Rosemary Betterton’s book Maternal Bodies in the Visual Arts investigates the practice by which the maternal “becomes embodied” in the European visual tradition. With a strong interest in the psychic development of the maternal subject, Betterton draws upon Adrienne Rich’s Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution and, most importantly, on the theory of abjection offered by Julia Kristeva, who gives useful accounts of psychoanalytical theories of the maternal.3 Despite the importance of R. Betterton’s book, which deals also with miscarriage and abortion, her investigation privileges a focus on the white maternal body only, embracing exclusively a western perspective. Discussing the work of Argentinian artist Nicola Costantino (born in 1964), Sophie Halart overcomes the limits of a European point of view, expanding the discussion on motherhood and femininity in relation to the Argentinian context and history.4

Approaching motherhood in terms of legislation and social issues, and contemporary art history respectively, Angela Davis and Andrea Liss constitute a fertile literary background on this subject. Davis discusses how African-American women were extorted from their children during slavery and how in turn they were seen as surrogate mothers – nannies – of more privileged white children. According to Davis, these women bear the evidence of colonisation.5

In 2009 A. Liss published Feminist Art and the Maternal, reflecting on motherhood in contemporary visual feminist art, and problematizing issues of intersubjectivity of the mother/feminist and the relation between the mother and the new born.6 A. Liss wittily addresses – investigating different media – issues concerning the pictorial legacy of slavery and maternity and the exoticization of the black body (among others), but her focus remains on the ethics of care and maternal narratives.

A subverted iconography of the maternal body – the focus of my text – responds to local traditions, religious values, and socio-political conditions in Latin America and, I argue, prompts what I would describe as “maternal artivism” – a neologism that combines “art” and “activism” – by exemplifying the understanding and representation of the body as a political apparatus, symptomatic of deeper issues.7 Indeed, these artists belong to a generation in which social and political concerns have become the very precondition of artistic production.

Marta María Pérez Bravo, No matar, ni ver matar animales III, from the series Para concebir, 1985-1986, photograph printed on paper, 22.5 x 28.5 cm, Colección de Arte del Banco de la República, Colombia, © Marta María Pérez Bravo

M. M. Pérez Bravo’s black and white photograph of a pregnant woman pointing a knife towards her own womb violently undresses the maternal body from its usual social stigmata and reveals the loneliness of pregnancy. M. M. Pérez Bravo’s No matar, ni ver matar animales III belongs to the series Para concebir [To conceive, 1985-1986], in which the artist records her pregnancy in a series of black and white photographs that bear utterly anti-romantic connotations. The title Do not kill animals or watch them be killed refers to the African-Cuban superstition according to which a woman will give birth to a child with a violent or criminal temperament if she either kills or witnesses the murder of an animal during her pregnancy. All the photographs in the series represent M. M. Pérez Bravo’s body parts through a religious lens and in a way that exorcises superstitious taboos. To this end, the artist’s crude depiction of maternity creates unexpected oxymorons: a carnal pregnant body, rendered with realism and portrayed naked in its visceral entirety, appears solemn, even as a place of worship; it’s enriched with sacred associations thanks to its references to traditions of Santería and Palo Monte – two African-Cuban religions that draw from Yoruba (western Africa) and Kongo-Angola (Central Africa) practices respectively.

While M. M. Pérez Bravo’s iconography is intertwined with local African-Cuban superstitions, concurrently J. Hamann portrays a dystopian representation of the pregnant body following a dialectic in which violence reflects violence. J. Hamann addresses the state of authoritarianism that Peru had suffered under general Alvarado’s military regime (1968-1975), including the lack of reproductive rights, of which Peruvian women were aware, as is demonstrated by contemporaneous studies.8

By sculpting maternal bodies with unusually tragic, violent and dramatic features, J. Hamann creates a great, rather unexpected, impact on the viewer. Barrigas [Bellies, 1983] consists of three plaster casts of pregnant abdomens in various stages of decomposition. Hanging on hooks, they resemble the animal carcasses that one would see at a butcher’s shop as well as the dissected pregnant wombs reproduced in eighteenth-century obstetric atlases, in which a new clinical aesthetics offered a spectacularised reproduction of pregnancy and birth.9 J. Hamann’s sculptural works insist on the representation of the body in its physical corporeality, often depicting it as suffering and mutilated; the body unfolds in the space, creating absurd, fragmented iconographies that play with planes and voids. In this dual and alien space, to use Julia Kristeva’s terms, both the subjectivities, of the mother and “the other”, are not only negated but shattered.

The depiction of motherhood is also the subject of Pregnant Woman in a Ball of Yarn (1978) by B. Carrasco, whose work focuses on the Chicana identity as well as on questions of gender and sexuality. The black and white drawing represents a pregnant woman trapped in a ball of yarn; one of the yarns – symbolising the umbilical cord – ends in a knitted baby’s shoe. The woman is portrayed bearing an unnatural posture, with her legs and arms firmly tied, and her mouth and eyes covered by the yarns so as to hide her identity. Her voluptuous breasts are accentuated by the strings around her body. Scholar Catherine S. Ramírez observes that such iconography “offers a powerful critique of motherhood and tempers the romantic portrayals of maternity offered by the cult of the Virgin of Guadalupe in particular”, thereby associating B. Carrasco’s portrait with the visual articulation of the Madonna as prescribed by the Mexican Catholic cult.10 B. Carrasco herself strengthens the association with the family-related Catholic patriarchal norms that affect Chicana women: the drawing depicts her sister-in-law forced by her husband to give up her studies to become a mother and housewife.

Josely Carvalho, A Espera [The Waiting], 1982, silkscreen and crayons on paper (diptych), 76,5 x 56.5 cm, Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, © Josely Carvalho

Similarly, J. Carvalho worked on a series of drawings later titled Na forma da mulher [In the shape of a woman, 1970-1986]. As the artist observes: “I use the female body to confront abuse, prejudice, attachments, achievements, power, and environmental destruction. She is everybody searching for a cultural identity…she is a subject, not an object.”11 Mapping the path of J. Carvalho’s representation of the female body as an “architecture of otherness”, we encounter A Espera [The Waiting, 1982], a triple and mirrored representation of a pregnant woman, showing the profile of her swollen womb both standing and lying down, as well as a headless torso.12 This work belongs to the series Maria in Exile (1981-83). Exile, migration and estrangement are recurring themes in the work of J. Carvalho, who emigrated from Brazil to the United States in the early sixties, right before the advent of the dictatorship. These circumstances are deeply entwined with her portrayal of the female body: “the meaning of exile refers to the personal and to the collective. Women can be exiled from their own body in many cases such as rape and birth. Women can create their own exile status emotionally and politically,” J. Carvalho reflects.13 The body has therefore the double nature of a shelter, a protective membrane in which the idea of a sanctuary comes back into play – “the body is the recipient/the shelter/the security we all pursue in a fragile world” – and a politically active battleground for reproductive rights: “I look for freedom – freedom of choice – how can love reside in a body that is not free to choose? How can a child grow in an undesired shelter?”.14

J. Carvalho’s use of silkscreen, photography and drawing, combined with the representation of the maternal body, deconstructs the codes of the old masters’ tradition by using techniques alien to a conventional repertoire and embedded with mass visuality. In this process, the body becomes a committed terrain, with its corporeality bearing the production of meaning and the subversion of power structures usually associated with language and visual signs.15

These few examples begin to construct a cartography in which the depiction of pregnancy unfolds in an array of meanings, prompting the emergence of a polyphony of voices speaking of an economy of shock by presenting an unexpected, unorthodox iconography. A corporeal, carnal depiction of the female body – which bears both monstrous and fetishised features in at least a couple of these examples – unites this selection of artists. Such dystopian, but compelling, iconography acts as a signifier for the structures of power enacted by religious traditions, socio-political issues, and patriarchal values. While these issues share a common substratum laid out by colonial histories, concurrently each artist in her work manifests local specificities that vary from country to country within Latin America. In this context, the pregnant body becomes a device used not only to reflect on motherhood and its relations to both contemporary art practice and contemporary social factors, but also to dismantle, according to a decolonial agenda, a-historical and stereotypical representations of the maternal often associated with western canons. As Kate Butler affirms in her review of Andrea Liss’ Feminist Art and the Maternal: “The relationship between motherhood and feminism is fraught with ambiguity. Feminist theorists, activists, and artists of the last half-century have struggled to reconcile patriarchal assumptions of mothering with their own feelings about feminist motherhood.”16

Adopting a visual strategy that recovers the tragic, creaturely, primordial and non-conciliatory values of maternity, the aforementioned artists investigate this experience from an unexpected and scandalising perspective: the pregnant body becomes the subject of a distressing and therefore eye-catching event, since – as Andy Warhol had already argued in the series Death and Disasters – there is nothing more spectacular than death and violence rendered with traumatic realism.

Dr. Lara Demori was awarded her Ph.D. in the History of Art from the University of Edinburgh with a thesis on artists Piero Manzoni and Hélio Oiticica. In 2018 Lara was the Goethe-Institut postdoctoral fellow at Haus der Kunst museum in Munich, where she worked on Okwui Enwezor’s project “Postcolonial Art: 1955–1980”, researching the iconography of pregnancy in Latin American women artists in the eighties, from a decolonial perspective. Lara has just been appointed Marcello Rumma Fellow in Contemporary Italian Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where she will relocate from September 2019.

Betterton Rosemary, Maternal Bodies in the Visual Arts, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1999, p. 1.

2

Until the end of the nineteenth century maternal bodies appeared in Catholic iconography of the “Madonna del Parto” (fourteenth to fifteenth century) and in obstetric atlases (eighteenth century). Across the centuries there are other examples of pregnant women represented in small, intimate, and private portraits, or in the guise of Flora, the goddess protecting parturiens.

3

Cf. Rich Adrienne, Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution, London, Virago, 1997 (republished); Kristeva Julia, “Motherhood According to Giovanni Bellini” in Desire in Language: a semiotic approach to literature and art, New York, Columbia University Press, 1980, p. 237-270; Kristeva Julia (translated by Arthur Goldhammer), “Stabat Mater,” in Poetics Today 6, issue: “The Female Body in Western Culture: Semiotic Perspectives”, 1985, pp. 133-152; Kristeva Julia and Clément Catherine, The Feminine and the Sacred, New York, Columbia University Press, 2010.

4

Halart Sophie, “Doubling the Odds: Pregnancy, Femininity and Embodiment in Nicola Costantino’s Trailer (2010)”, forthcoming (2019) in a volume edited by Mary Edwards, and published by McFarland.

5

Cf. Davis Angela Y., Women, Race and Class, New York, Random House, 1981.

6

Cf. Liss Andrea, Feminist Art and the Maternal, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

7

I borrow this term from Julia Antivilo Peña’s talk Artivismo. Il femminismo per strada, in casa, a letto (Artivism. Feminism on the street, in the house, in bed), held at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Rome, 28th September 2018; cf. also Julia Antivilo Peña, Mónica Mayer and María Laura Rosa,‘Feminist Art and “Artivism” in Latin America: a Dialogue in Three Voices’ in Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and Andrea Giunta, Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985, Munich, London, New York, DelMonico Books, Prestel, 2017, pp. 37 – 41.

8

The pivotal work by artist Teresa Burga (born in 1935) Perfil de la Mujer Peruana [Profile of the Peruvian Woman, 1980-1981] – realised in collaboration with psychologist Marie-France Cathelat – also provides an important insight on this matter (two years before Perfil de la Mujer Peruana, in 1979, Maruja Barrig had published the book Cinturón de castidad [‘Chastity Belt’] which analysed the conditions of urban middles class women in Peruvian society).This collaborative project took the shape of a long survey addressed to middle-class women in Lima between the ages of 25 and 29. The questions were structured around twelve profiles (physiological, psychological, emotional, social, educational, cultural, religious, professional, work, economic, legal and political) and the results were converted into graphs and charts which were displayed alongside installations. M-F. Cathelat saw the work as a means of rejecting “the acquired concepts according to which we think and say what a woman is, can, or must be.” One of the issues emerging from the data collected was the demand for the legalization of abortion, together with the refusal of the role of the woman as housewife and mother, imposed by patriarchal traditions and Catholic values (with the exceptions of Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guyana and Uruguay abortion upon request is illegal in all Latin American countries).

9

Cf. Massey Lyle, “Pregnancy and Pathology: Picturing Childbrith in 18th c. Altlases,” Art Bulletin 87, 2005, p. 73-91.

10

Ramírez Catherine S., The Woman in the Zoot Suit: Gender, Nationalism, and the Cultural Politics of Memory, Durham, Duke University Press, 2009, p. 114. Re. the importance of the Virgen de Guadalupe as associated to ethnic stereotypes, see for example the tableaux vivant by Yolanda M. López, in which the Chicana artist positions herself (or her family members) in the guise of the Virgin in the mandorla, creating playful sceneries (these humanized virgins wear athletic clothes or perform domestic or other labours).

11

Carvalho Josely, Diary of Images,Rio de Janeiro/ New York, Contracapa, 2018, p. 113.

12

Ibidem.

13

From an interview that the author had with the artist herself, January 2019.

14

Ibidem.

15

Cf. Grosz Elisabeth, “Inscriptions are Body-Maps: Representation and the Corporeal” quoted in Robinson Hilary (ed.), Feminist Art Theory: An Anthology 1968–2014, Hoboken, John Wiley & Sons, 2015, p 124.

16

Butler Kate, “Liss Andrea. Feminist Art and the Maternal”, Visual Studies 25, 2010, p. 193.

Lara Demori, "Maternal artivism: a brief overview of Latin American women artists in the eighties." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/artivisme-maternel-tour-dhorizon-des-artistes-latino-americaines-des-annees-1980/. Accessed 1 July 2025