Asuka Tsuboi

Tsuboi Asuka: Waga kokoro no kiseki [Asuka Tsuboi: The path of my heart], exh. cat. Paramita Museum, Mie, Japan (November 3-December 26, 2010), Mie, Paramita Museum, 2010

→Sugiura, Sumiko, Tsuboi, Asuka, Tsuji, Kyō, “Josei tōgeika no arikata [The state of women potters]”, in Gendai no tōgei 14 [Contemporary ceramics, vol. 14], Tokyo, Kōdansha, 1977

→Tsuboi Asuka, World of Ceramics, exh. cat., Ginza Wako, Tokyo (September 21-29, 1982), Tokyo, Ginza Wako, 1982

Asuka Tsuboi: The Path of My Heart, Paramita Museum, Mie, November 3-December 26, 2010

→Ceramics: The Japanese Avant-Garde and Tradition, Musée national de céramique, Sèvres, November 17, 2006-February 26, 2007

→Tsuboi Asuka, World of Ceramics, Ginza Wako, Tokyo, September 21-29, 1982

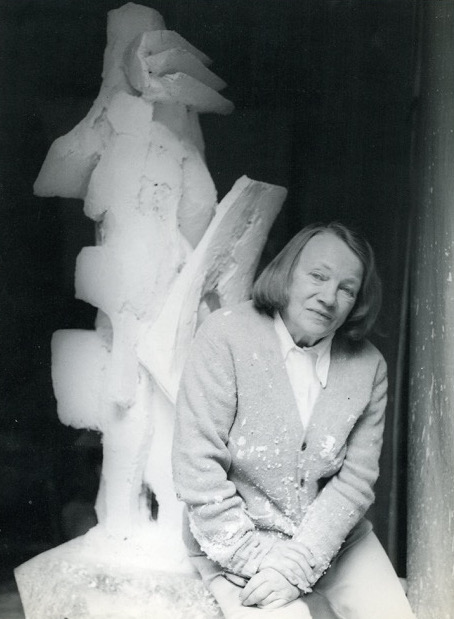

Japanese ceramic artist.

Asuka Tsuboi spent her childhood in Tokyo, studying under sculptor Takashi Shimizu (1897-1981) at the arts-education-focused Jiyu Gakuen School. Hoping to become a potter, she moved to Kyoto in 1953 and enrolled in Yūsai Kōgei at Sennyūji. From 1954 she apprenticed under the potter Kenkichi Tomimoto (1886-1963). During that period she exhibited work at the Shinshō-kai Exhibition (now the Shinshō Kōgei-kai Exhibition), which was then overseen by K. Tomimoto. In 1976 she withdrew from that organisation. At a time when women potters were scarce, K. Tomimoto initially suggested A. Tsuboi create small works, such as accessories, but he later changed his mind, advising her to learn all the core ceramics techniques, from clay moulding to wheel throwing, pottery firing and ceramic painting.

Pottery, a Japanese traditional craft, was accompanied by its own conservative conventions. In the 1950s women, who were considered tainted by the stain of physical pollution, were not permitted to enter the communal climbing kilns of Kyoto when they were lit. In response A. Tsuboi founded the Women’s Association of Ceramic Art in 1957. This organisation was designed to enable connections between the few women potters working at that time: at its founding the association had seven members. In 1959 the group held its first exhibition and has grown significantly since 1967, when its exhibition was opened to the public and began inviting applications from women potters across the country. As a founder and a representative of the association, A. Tsuboi laboured diligently on its behalf.

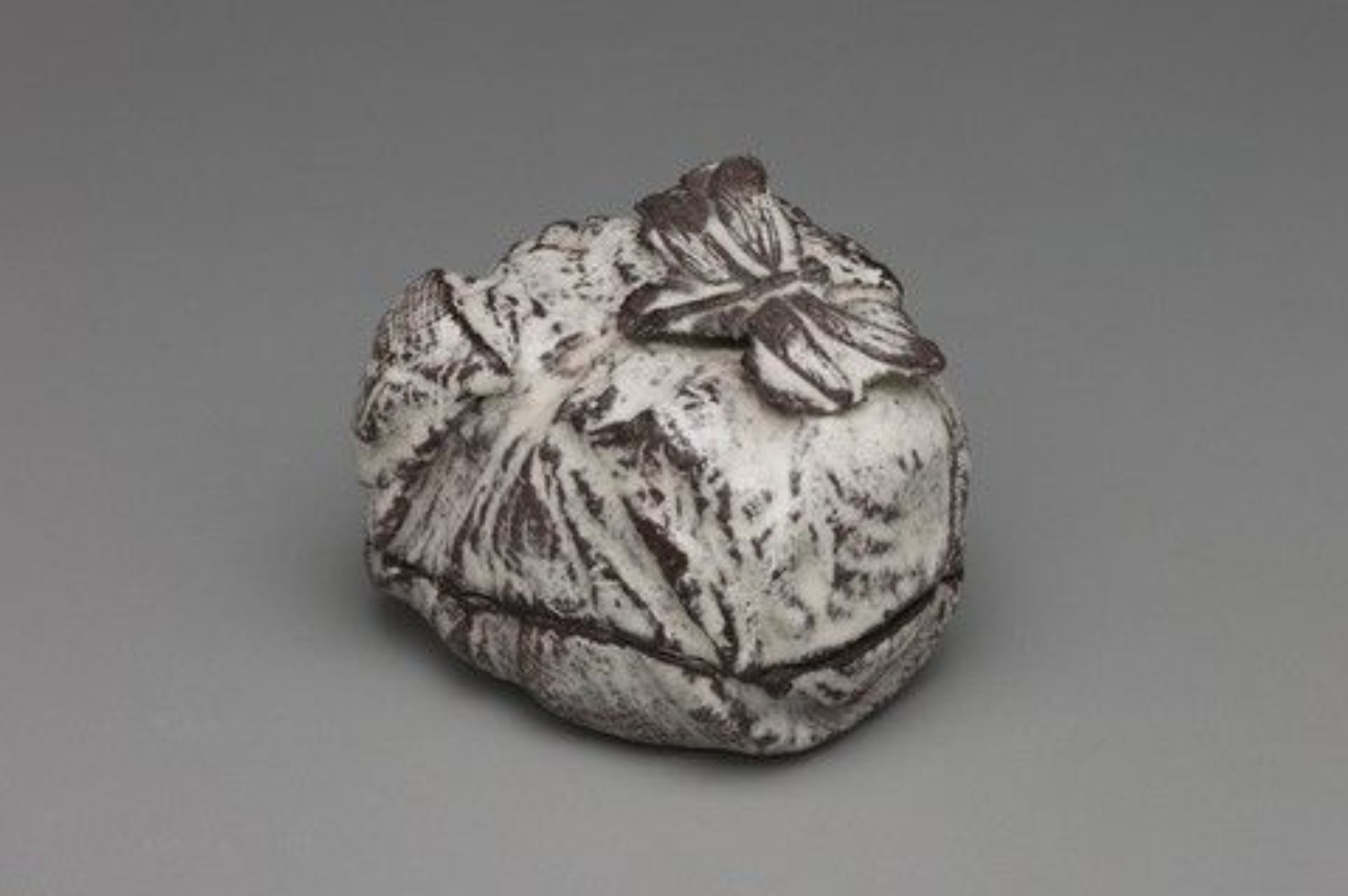

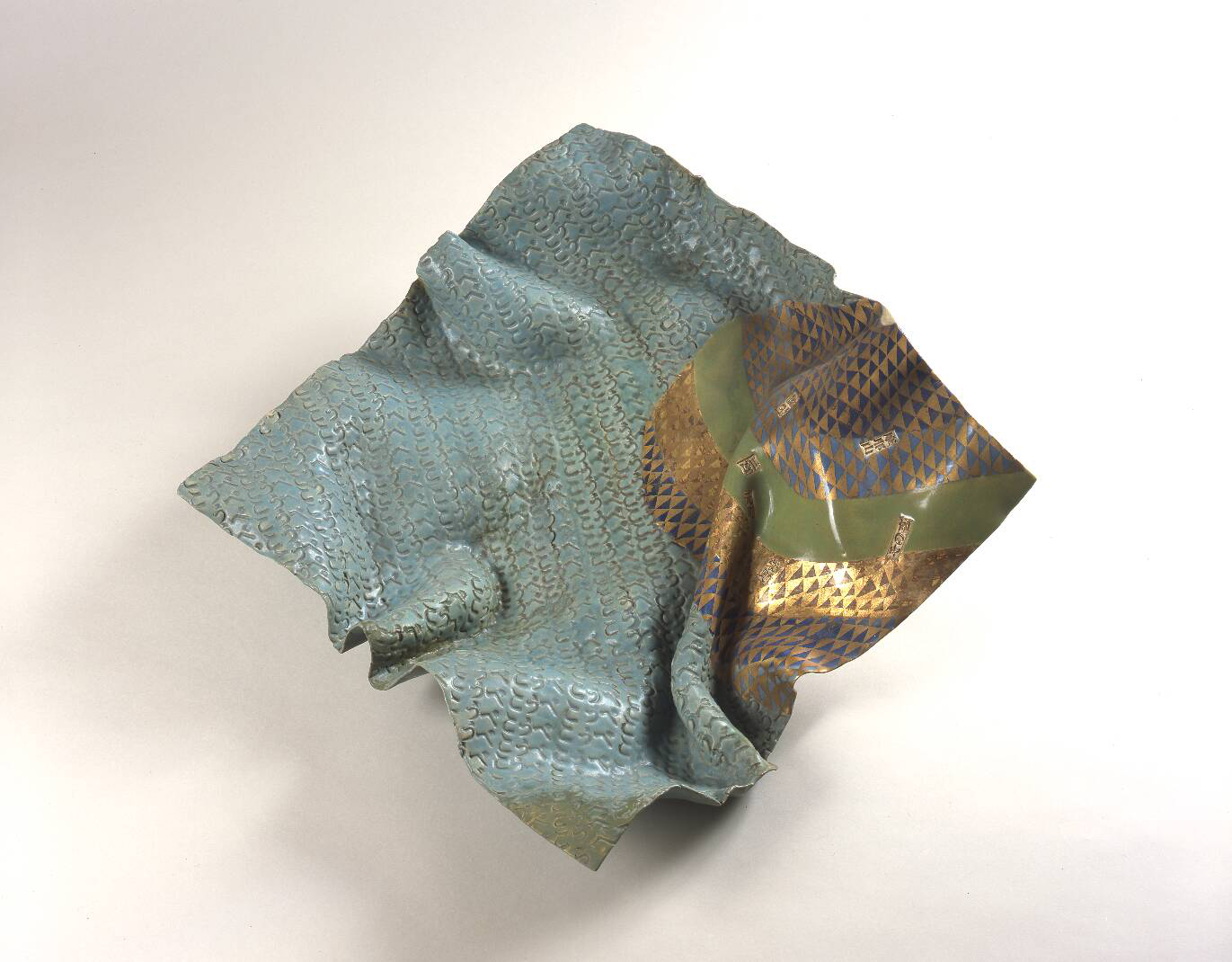

In 1966 she spent fifty days in China during the intense early days of Cultural Revolution as a member of a delegation of Kyoto craft artists to China. Given the opportunity to view Chinese pottery during this visit, A. Tsuboi began exploring artistic expressions based on her own time and place. Though she initially produced everyday handcrafts like dishes and tea bowls, after this experience A. Tsuboi developed an interest in avant-garde ceramics and began creating works rich in both implicit and explicit sensuality. In 1970 she exhibited the piece Furoshiki [Wrapping Cloth] at the Contemporary Ceramic Art: Europe and Japan exhibition held at the National Museums of Modern Art in both Kyoto and Tokyo. The expression in pottery of such a light and supple cloth, one that could perhaps be used to cover a woman’s body was considered erotic. In 1971 at the Contemporary Ceramic Art: USA, Canada, Mexico and Japan exhibition, again at the same museums in Kyoto and Tokyo, she exhibited Fueshi no tawamure [Piper’s Caprice], whose conflicting elements of strict cubes and cylinders and organic shapes evoking plants and female genitalia combine to produce a sense of sensual tension. In 1973 she exhibited the pieces Nugeta kappu [Nude Cup], Kanraku no kinomi [Fruit of Pleasure] and Kindan no kinomi [Forbidden Fruit] at the Bird’s Eye View of Contemporary Crafts exhibition at the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto. A. Tsuboi’s bold application of gold and silver glaze to the motif of women’s breasts in these works shocked the ceramic art world at the time. Sensual bodily motifs appeared in her work from that time on. However, A. Tsuboi, who had been making pottery while steeped in the atmosphere of Kyoto, was cognisant of the relationship between her own work and the Kyō ware of Kyoto. As can be seen from the Chizuzara [Plate Maps, 1977] and Karaori bukuro [Karaori-Weave Bags, 1981] series, her tactile and trompe l’oeil representations of slender and ephemeral subjects such as cloth, paper and leaves overflow with the elegant decorativeness and playfulness of Kyoto pottery.

A notice produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2022