Augusta Curiel (Augustina Cornelia Paulina Curiel)

De Boer, Agnes, “Curiel, Augusta Cornelia Paulina (1873-1937)”, Digitaal Vrouwenlexicon van Nederland, Huygens Institut.

→Van Dijk, Janneke, Hanna van Petten van Charante, and Laddy van Putten, Augusta Curiel, Fotografe in Suriname 1904-1937, Libri Musei Surinamensis 3, Amsterdam, KIT Publisher, 2007.

→Knops, Marleen, Suriname door het oog van Augusta Curiel. Antropologische analyse van Suriname en ‘Surinamers’ op fotomateriaal van Fotostudio Augusta Curiel, 1904-1952, Paramaribo, Suriname, Amsterdam, 2005.

Pioniers – Fotografie door vrouwen, Nationaal Archief, The Hague, 1 December 2023 – 30 June 2024

→Surinamese school : Painting from Paramaribo to Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 12 December 2020–11 July 2021

→De Vrouw 1813-1913, Meerhuizen, Amsterdam, 2 May–30 September 1913

Surinamese photographer.

Augusta Curiel grew up in a well-to-do family in Paramaribo at the end of the nineteenth century. Her mother, Henriette Curiel, indicated ‘unknown’ for the father on the birth certificates of all four of her children. Their heredity is thus easier to trace on the maternal side of the family, through their Portuguese Jewish grandfather, Mozes Curiel, who settled in Amsterdam and married an enslaved woman, Elisabeth Nar, thereby emancipating her. A. Curiel’s family belonged to the Lutheran Church, one of whose preachers was an amateur photographer, a possible clue to the inspiration behind the budding professional’s future vocation. In 1904, at the age of thirty-one, A. Curiel opened her own photography studio in a building adjacent to the home where she lived with her two sisters, Anna (1875-1958) and Elisabeth (1869-1937). The ‘Curiel Ladies’ never married.

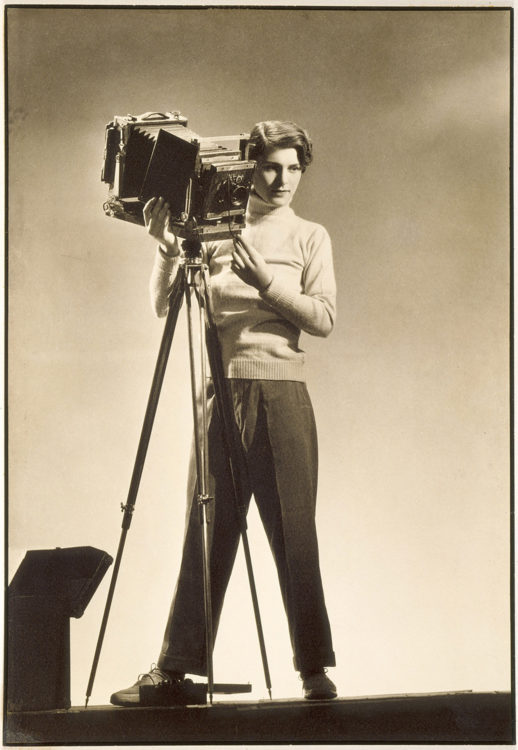

Unlike William George Cornelis Amo (1882-?), another photographer from Paramaribo who made the only known portrait of A. Curiel, she did not work in a studio but outdoors, using a tripod plate camera with glass negatives measuring 18 x 24 or 13 x 18 cm. Despite her predilection for photographing her subjects in the open air, she did not make use of a light meter. According to first-hand accounts, it was her sister Anna who helped her calculate the exposure time for the poses according to the amount of sunlight available. Her early photographs were covered in emulsion and protected by a layer of varnish before the advent of ready-to-use negatives. To maintain an optimum temperature for the chemical products required for developing and printing, the family arranged for regular deliveries of ice blocks. Each customer received three prints and the glass plates were then either kept for further prints or recycled. The Curiel sisters are known to have taken thousands of photographs in the first half of the twentieth century, 1,200 of which are still accessible, the prints, glass plates, postcards, and albums housed in museums in Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and Paramaribo having been digitised and posted on their respective websites.

A. Curiel took solo portraits of individuals and dignitaries as well as group portraits at weddings and schools. She became the appointed photographer for official and promotional events highlighting business life in the capital and small towns and on the plantations of inland Suriname. In 1913, she featured in the exhibition De Vrouw 1813-1913 [Woman 1813-1913], which drew around 300,000 visitors to its Amsterdam venue. In the 1920s, with a view to later publications, A. Curiel and her sister took part in botanist Gerold Stahel’s scientific expeditions in the colony’s interior. In 1928, at the request of Suriname’s governor, A. Curiel became court photographer and a year later, Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands appointed her official photographer to the Crown.

Photography became widespread throughout South America in the mid-nineteenth century, largely due to the emergence of urban portrait studios such as A. Curiel’s. Right up to her death in 1937 (at which point her sister Anna took over, continuing until 1950), A. Curiel responded with consummate skill to an ever-broader palette of commissions, almost always taken on the spot, providing a unique, yet not strongly critical, visual account of the Dutch colony of Suriname.

A biography produced as part of the project “Related”: Netherlands – Caribbean (XIXth c.–Today)

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2023