Betye Saar

Cochran Sara, Betye Saar: Still tickin’, exh. cat., municipal theater De Domijnen, Sittard (July 28 – November 15, 2015); Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Scottsdale (January 30 – May 1st, 2016), Scottsdale, Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, 2017

→Mainetti Mario, Betye Saar: Uneasy Dancer, exh. cat., Foundation Prada, Milan (September 15, 2016 – January 8, 2017), Milan, Fondation Prada, 2016

→Ulmar Sean M., Derosier Weiss Katharine, Betye Saar: Extending the Frozen Moment, exh. cat., University of Michigan museum of art, Ann Arbor (October 15, 2005 – January 8, 2006); Norton museum, West Palm Beach (March 18 – June 11, 2006); Pennsylvania academy of the fine arts, Philadelphia (September 8 – December 3, 2006)

Betye Saar: The Legends of Black Girl’s Window, Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 21, 2019 – January 4, 2020

→Family legacies: the art of Betye, Lezley and Alison Saar, Ackland Art Museum, the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, Ackland, December 18, 2005 – March 26, 2006; Pasadena Museum of California Art, Pasadena, April 30 – September 24, 2006; Museum of Art, San Jose, October 21, 2006 – January 7, 2007; Palmer Museum of Art, the Pennsylvania state University, Palmer, January 30 – April 22, 2007

→Betye Saar: Extending the Frozen Moment, University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor, October 15, 2005 – January 8, 2006; Norton Museum, West Palm Beach, March 18 – June 11, 2006; Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, September 8 – December 3, 2006

American sculptress.

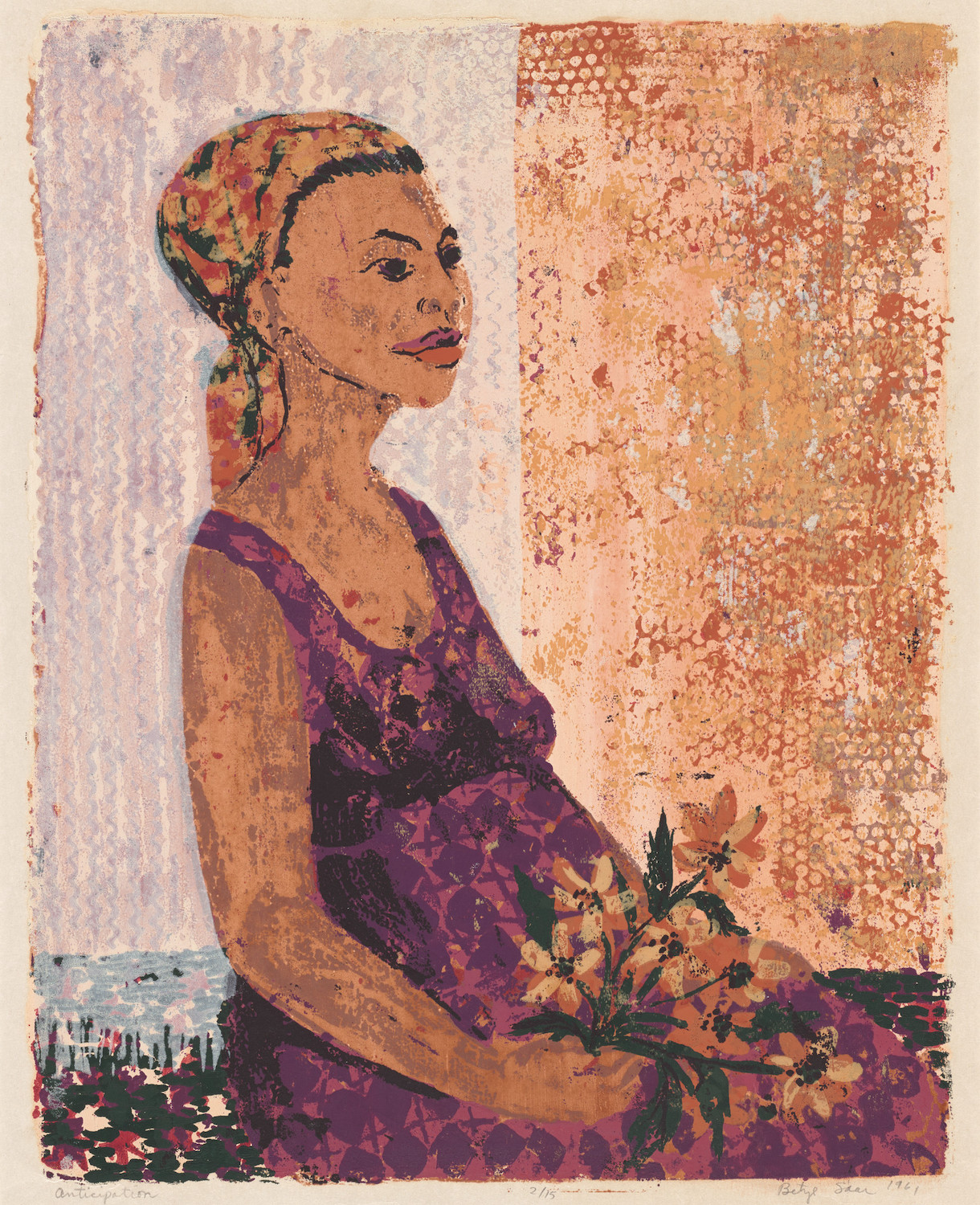

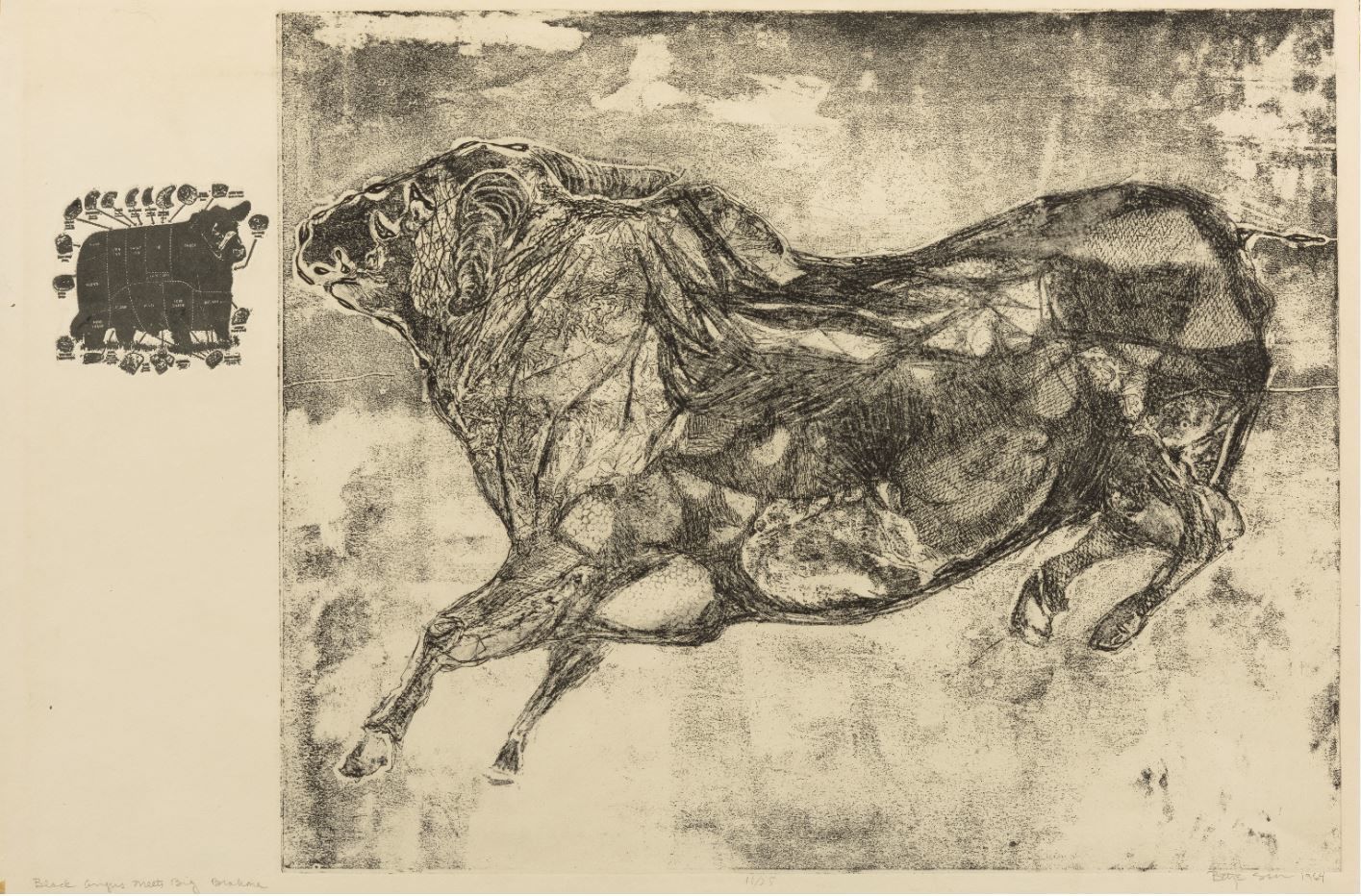

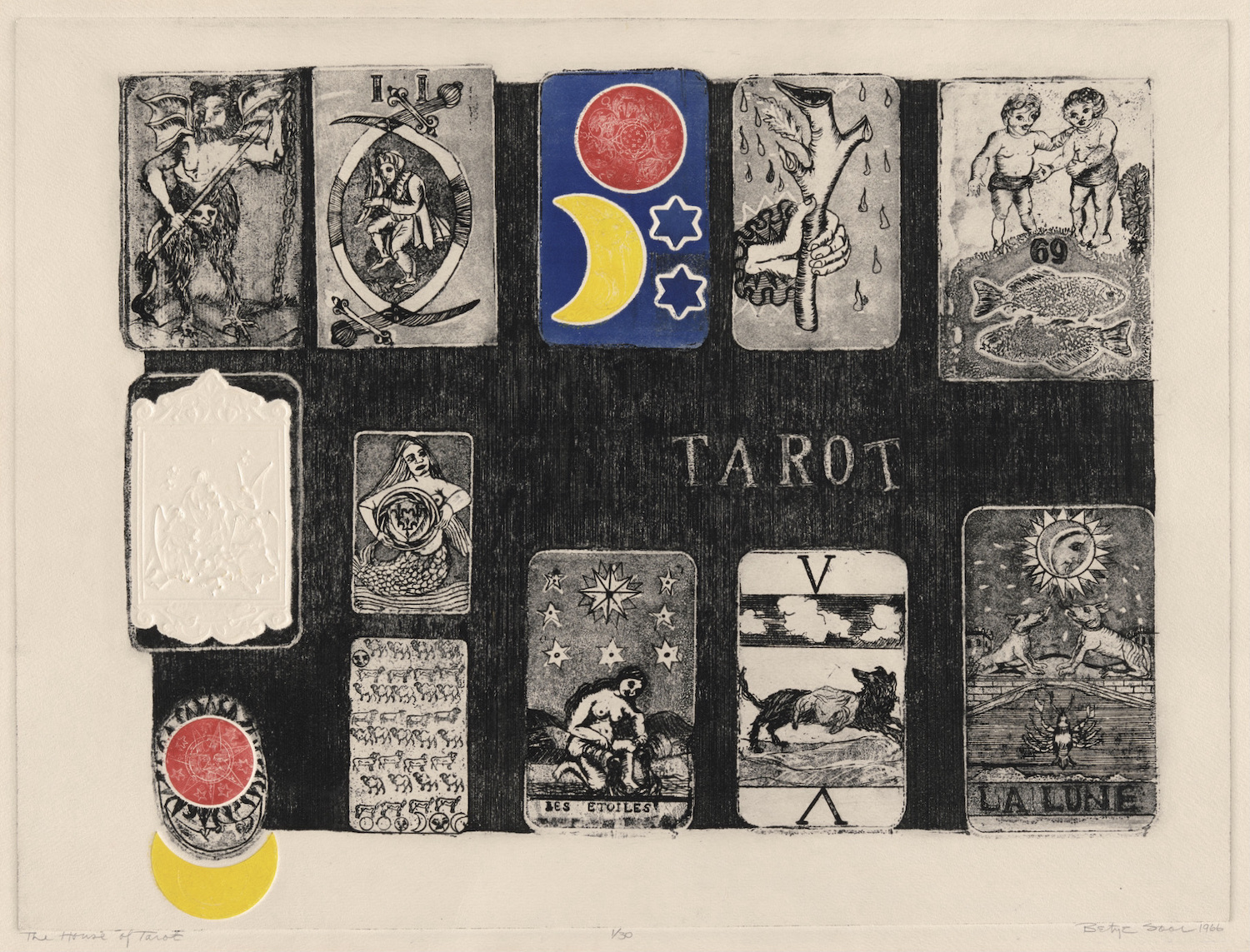

Betye Irene Brown first attended art classes as a teenager (in ceramics, history of art and watercolour) before going on to study interior and textile design, bookbinding and illustration at the University of California in Los Angeles. In the early 1950s she and Curtis Tann (1915-1991) launched a jewellery and enamel design company known as Brown and Tann. Following her marriage to Richard W. Saar (1924-2004) and the birth of her first two daughters, she resumed her studies, in engraving in particular, accompanied by her youngest child, a factor that was to have a crucial impact on her work. She moved within Black artistic circles and was strongly influenced by counterculture, mysticism and occult imagery. When her third daughter was born in 1961, she produced engravings depicting her pregnancy and childbirth. After 1964 she leaned more towards drawing, and collaborated on a variety of artistic projects protesting the Vietnam War and in support of civil rights, and became a key figure in the Black Arts Movement. In 1967, following her discovery of the oeuvre of Joseph Cornell (1903–1972) through an exhibition at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, she began creating assemblages and found herself increasingly absorbed by her African-American and African heritage. She trawled flea markets and garage boot sales for stereotypical depictions of Black men and women through the prism of popular American culture (advertisements, toys, postcards, and such) integrating them within syncretic assemblages that hovered between magic, irony and tenderness.

Having taken up professorships at a number of American universities, in 1972 she produced her most famous work, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, a twist on the clichéd image of the Black woman derived initially from minstrel shows and later taken up by the manufacturing industry as a way of promoting their food products. Traditionally portrayed as a servant devoted body and soul to the well-being of her White masters, B. Saar transforms her into a political icon emancipated from the dominations of the past. This is reflected in the artist’s assemblages, which meld popular racist-tainted imagery with a radical stance and underlying wry humour. Over the course of the decade her works took on new sculptural forms redolent of altars. She made recurrent use of old photographs, overlapping autobiographical accounts with tributes to iconic Black women such as Biddy Mason and Rosa Parks. Her career grew; she devoted more and more time to her artistic pursuits and in 1974, among other destinations, travelled to Haiti, Mexico and Nigeria.

The 1980s saw the development of her large composite installations. At the turn of the following decade she created The House of Gris Gris (1990) with her daughter Alison Saar (b. 1956). The 2000s consecrated institutional recognition of her oeuvre, in the form of her first major solo exhibition (2003), followed by an exhibition at Ackland Art Museum in Chapel Hill (2005-2006), spanning forty years of her own work alongside that of her daughters Lezley (b. 1953) and A. Saar. The artist’s mantra was still underpinned by an ardent desire to interweave the poetry of forms with a radical message, as highlighted in the catalogue Betye Saar / Colored: Consider the Rainbow in 2002: “It is my goal as an artist to create works that expose injustice and reveal beauty.”

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2021

Exhibition Walkthrough, Betye Saar: Call and Response | Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Exhibition Walkthrough, Betye Saar: Call and Response | Los Angeles County Museum of Art