Carla Accardi

Gianelli Ida (ed.), Carla Accardi, exh. cat., Rivoli, Castello di Rivoli, Museo d’arte contemporanea (1994), Milan, Charta, 1994

→Celant Germano, Carla Accardi : la vita delle forme / the life of forms, Cinisello Balsamo, Silvana, 2011

→D’Amico Fabrizio (ed.), Carla Accardi timeless / Carla Accardi senza passato, Poggibonsi, Cambi, 2017

Carla Accardi: Triplice Tenda, MoMA PS1, New York, 20 May – 3 September 2001

→Carla Accardi, Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris, Paris, 17 January – 3 March 2002

→Carla Accardi : segno e trasparenza, Fondazione Puglisi Cosentino, Catania, 6 February – 12 June 2011

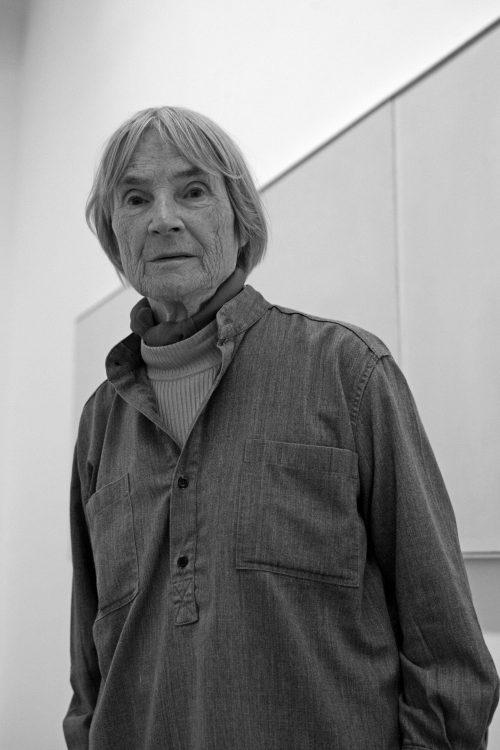

Italian painter.

Carla Accardi is one of the major figures of Italian formalism. Her abstract paintings and artistic explorations relate primarily to symbols, which are integrated into her works in modular series. In 1944, just after the liberation of Sicily, she moved to Palermo to train at the Academy of Fine Arts. This is where she met painter Antonio Sanfilippo, whom she married in 1949 and with whom she has a daughter. She later studied at the Academy in Florence, but its overly figurative and academic orientation soon disappointed her.

In 1946, she followed her husband to Rome and produced paintings based in geometric abstraction, linking her with the pioneers of non-figuration, such as Kandinsky, Mondrian, and Klee. This approach brought her closer to Giulio Turcato, Pietro Consagra, Achille Perilli, and Piero Dorazio, all of whom joined her in founding Forma 1 in 1947. The group published a Marxist-inspired manifesto in which it positioned itself at odds with pre-war Italian trends of figuration. As formalists, the artists proclaimed that form is “the means and ends” of art. C. Accardi also belonged for some time to the Italian Communist Party, before it declared itself in favour of figurative realism in 1948. The radicalism of her artistic approach contributed to a restoration of her country’s place in the international art scene. Forma 1 maintained connections with France, and the painter’s work was defended by informalist critic Michel Tapié, and by Pierre Restany, the theorist of the nouveaux réalistes. In Italy, her work was supported by gallerist Luciano Pistoi (1927-1995) from 1957.

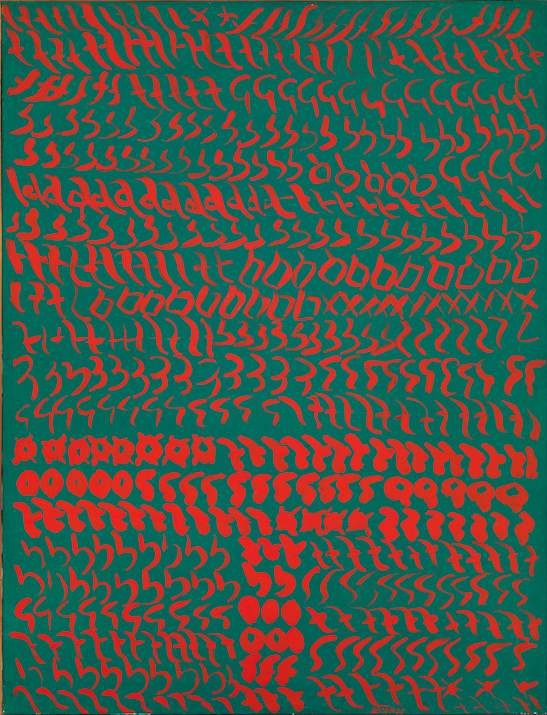

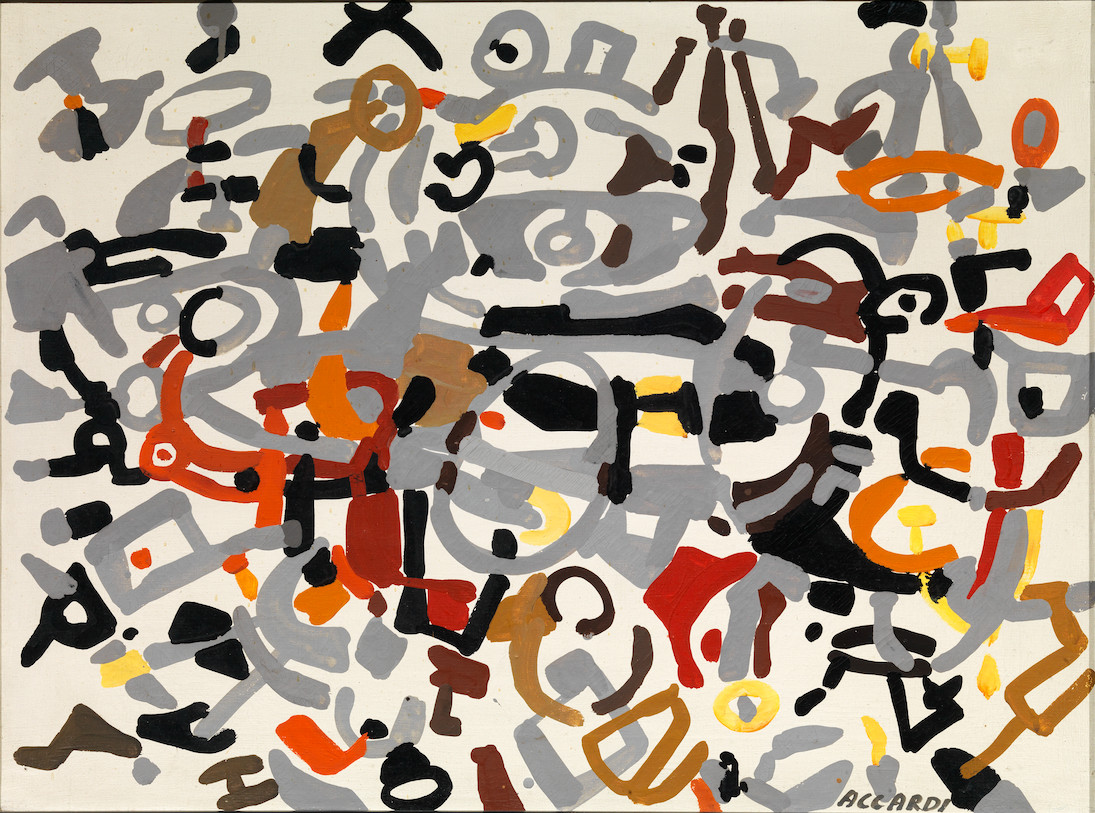

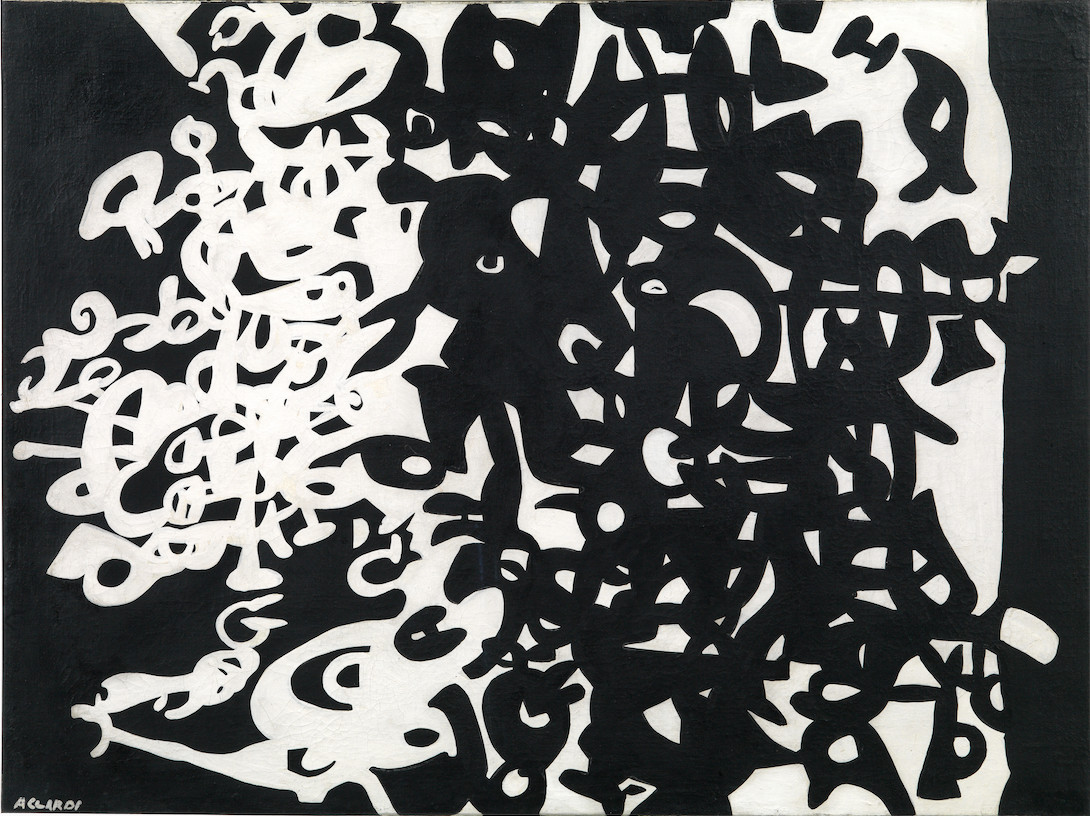

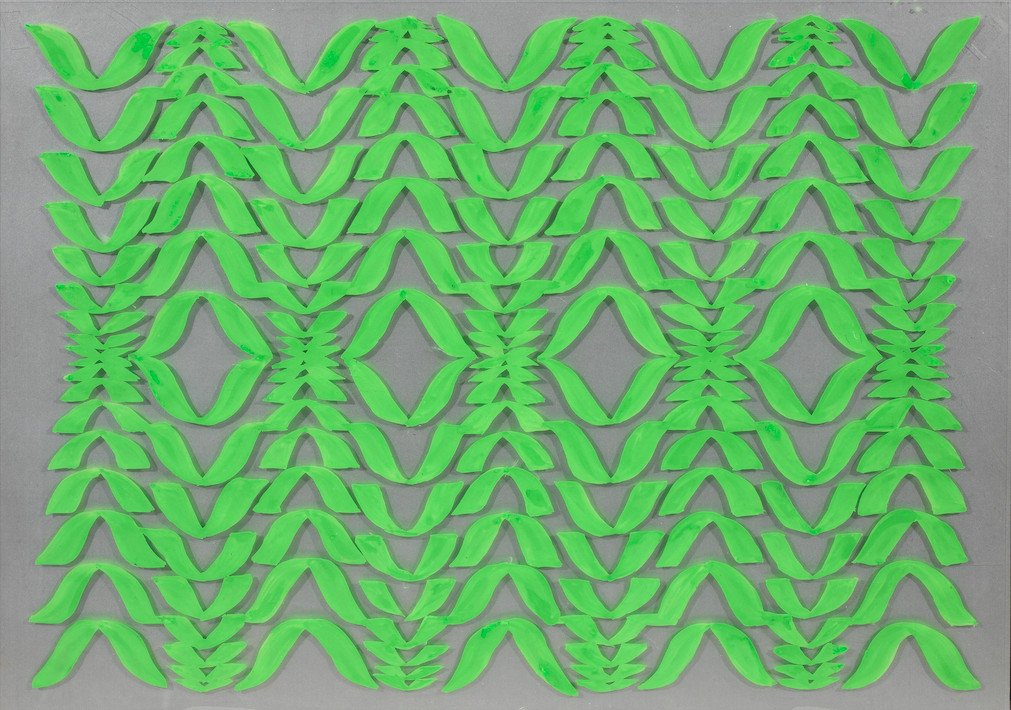

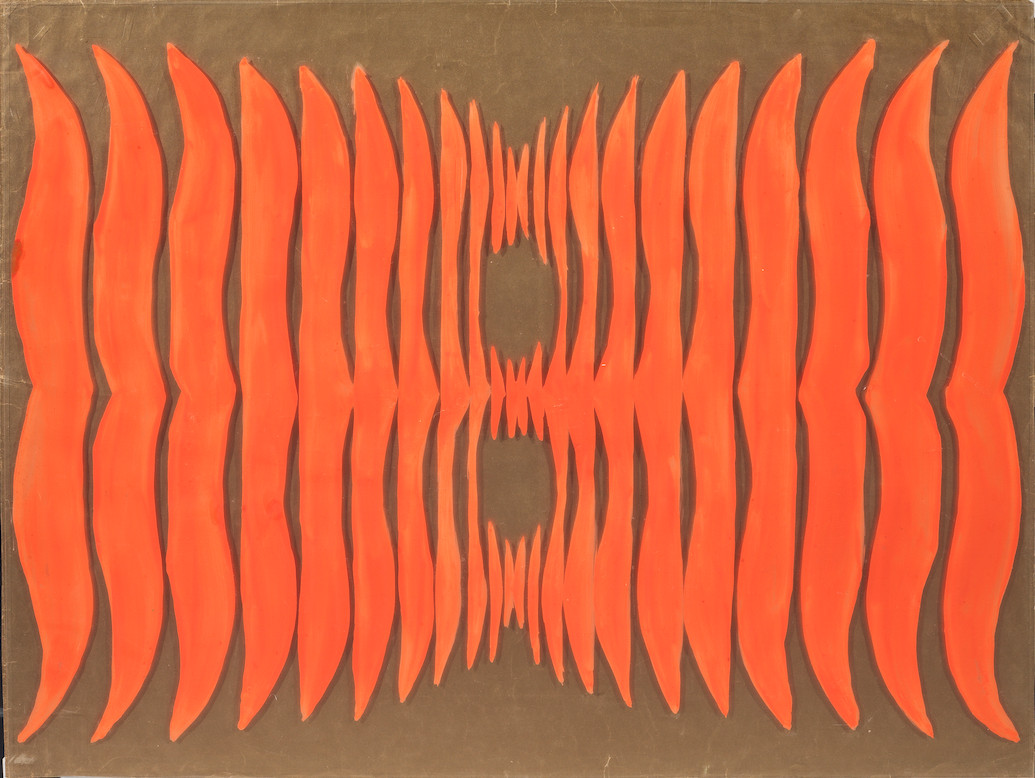

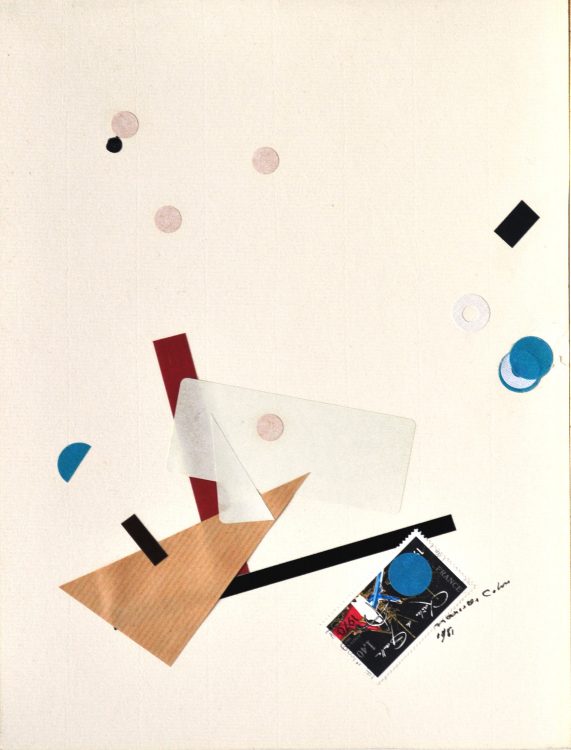

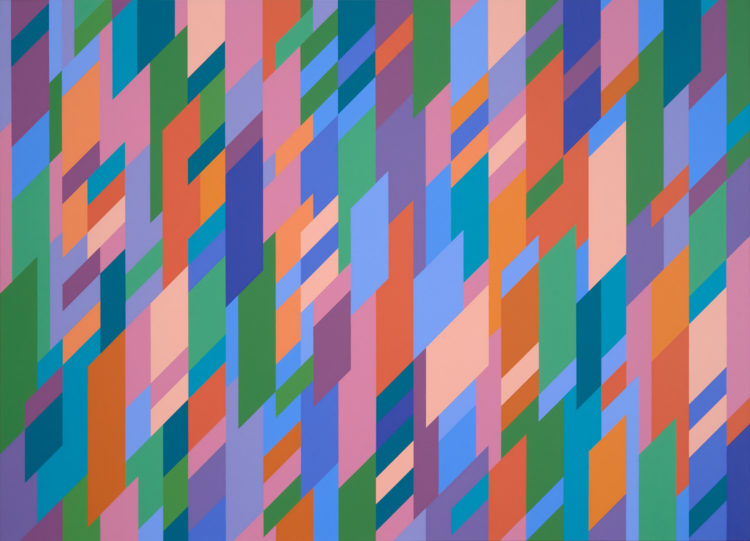

In the early 1950s, she started painting on the floor, in black and white, in a style similar to informalism, influenced by a visit to the studio of Hans Hartung (1904-1989). She subsequently introduced colour into her paintings, including fluro colours, whose brightness she made great use of in the 1970s. In her works from this period, she juxtaposed pure, non-complementary colours, in variations on tones of similar bright intensities, producing sophisticated effects of contrast between the background and the series of signs inscribed on it. During the 1950s, her work on symbols became more structuralist: as the urgent search for a new pictorial grammar became palpable, she strove to explore the basic unit of language. Her work, pervaded with a tension between the coldness of the sign and the poetic potential it unleashes when it is repeated in a free yet serial manner, was to remain marked, from this point on, by a two-pronged nature: essentialist and structuralist. Interested in the relationship between the symbol and its space, C. Accardi started working in the early 1960s on transparent plastic media from the Sicofoil brand – a material considered in very poor taste at the time – onto which she drew signs. Light itself became a plastic element – a medium that the artist could manipulate – and the strips of plastic were stretched over frames so as to cover them according to a chosen design.

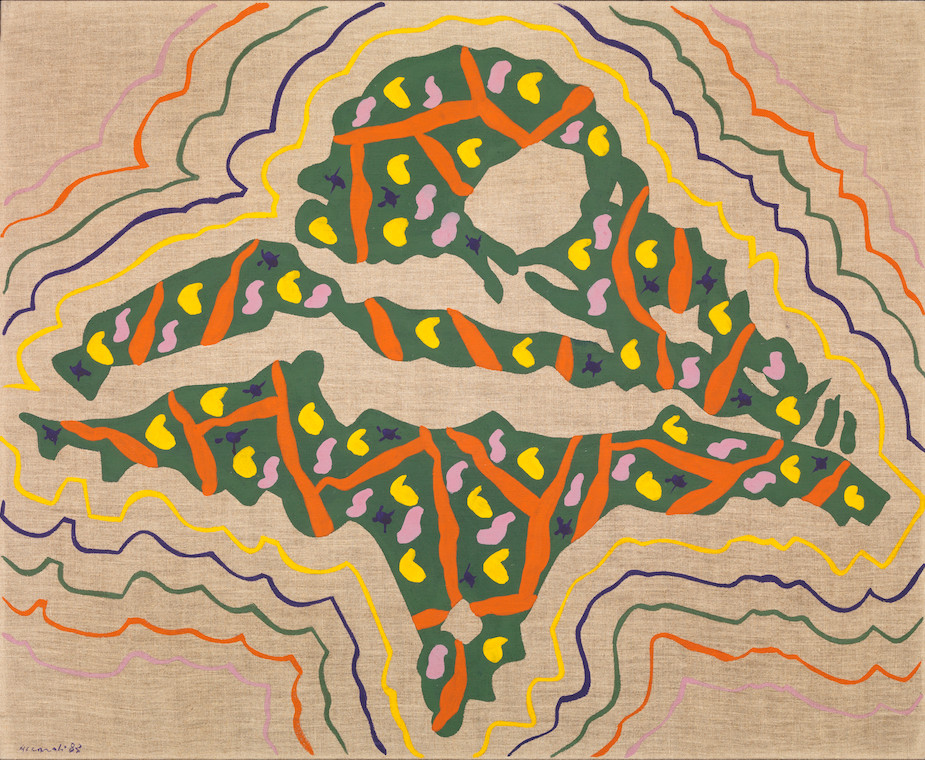

In 1964, the painter exhibited at the Venice Biennale, attracting international attention. The following year, she created her first tents (tende), which encapsulated her thinking on ways of occupying space; these structures were designed as complete environments in the form of small temples or rudimentary houses, inviting visitors to walk through them, and were covered in a transparent plastic that vibrated and gave unexpected life to the colourful symbols decorating them. In the 1970s, C. Accardi returned to painting on canvas, but without abandoning the principle of “anti-painting” that had defined all of her previous work. In the same period, together with critic Carla Lonzi, she created the cooperative Beato Angelico, which exhibited forgotten female artists of the past, such as Artemisia Gentileschi or Angelika Kauffman. She was therefore close to feminist trends but eventually detached herself from them, deeming the movement too “political”. Today, she continues to paint on raw canvas. She was again present at the 1988 Venice Biennale. In 1996, she became a member of the Brera Academy in Milan and the following year she joined the Venice Biennale commission. Her works are notably conserved at the Galleria nazionale d’arte moderna in Rome and at the Peggy Guggenheim collection in Venice.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2018

Carla Accardi, la signora dell`astrattismo

Carla Accardi, la signora dell`astrattismo