Dorothea Lange

Borhan Pierre, Dorothea Lange, le cœur et les raisons d’une photographe, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 2002

→Partridge Elizabeth, Restless Spirit: The Life and Work of Dorothea Lange, New York, Puffin Books, 2001

Dorothea Lange, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 26 January–10 April 1966

→Dorothea Lange, American Photographs, Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, 1994

→Dorothea Lange: The Human Face, Tour du Lépreux, Aoste; Kunsthal, Rotterdam; Suermondt-Ludwig-Museum, Aachen, 1998–1999

American photographer.

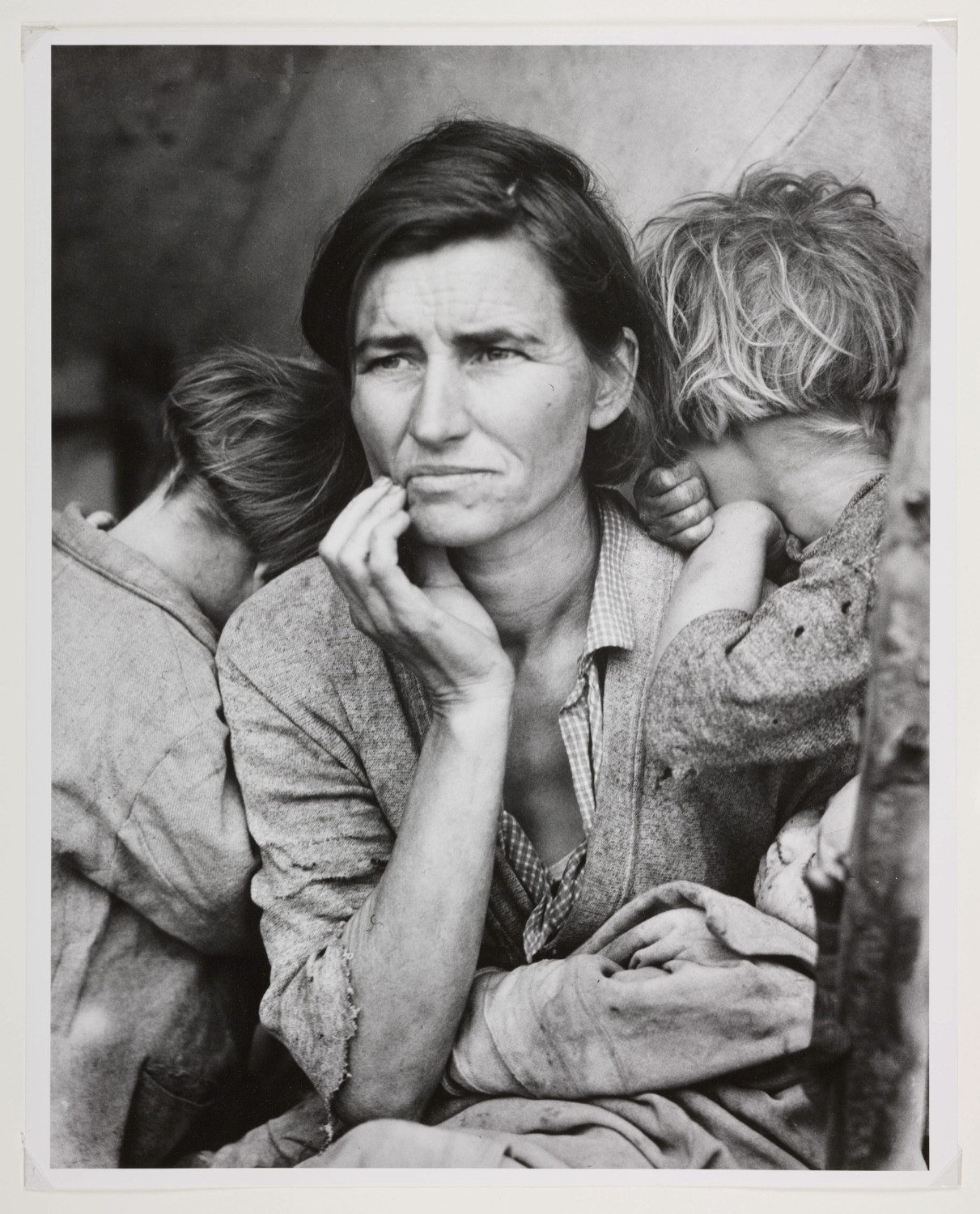

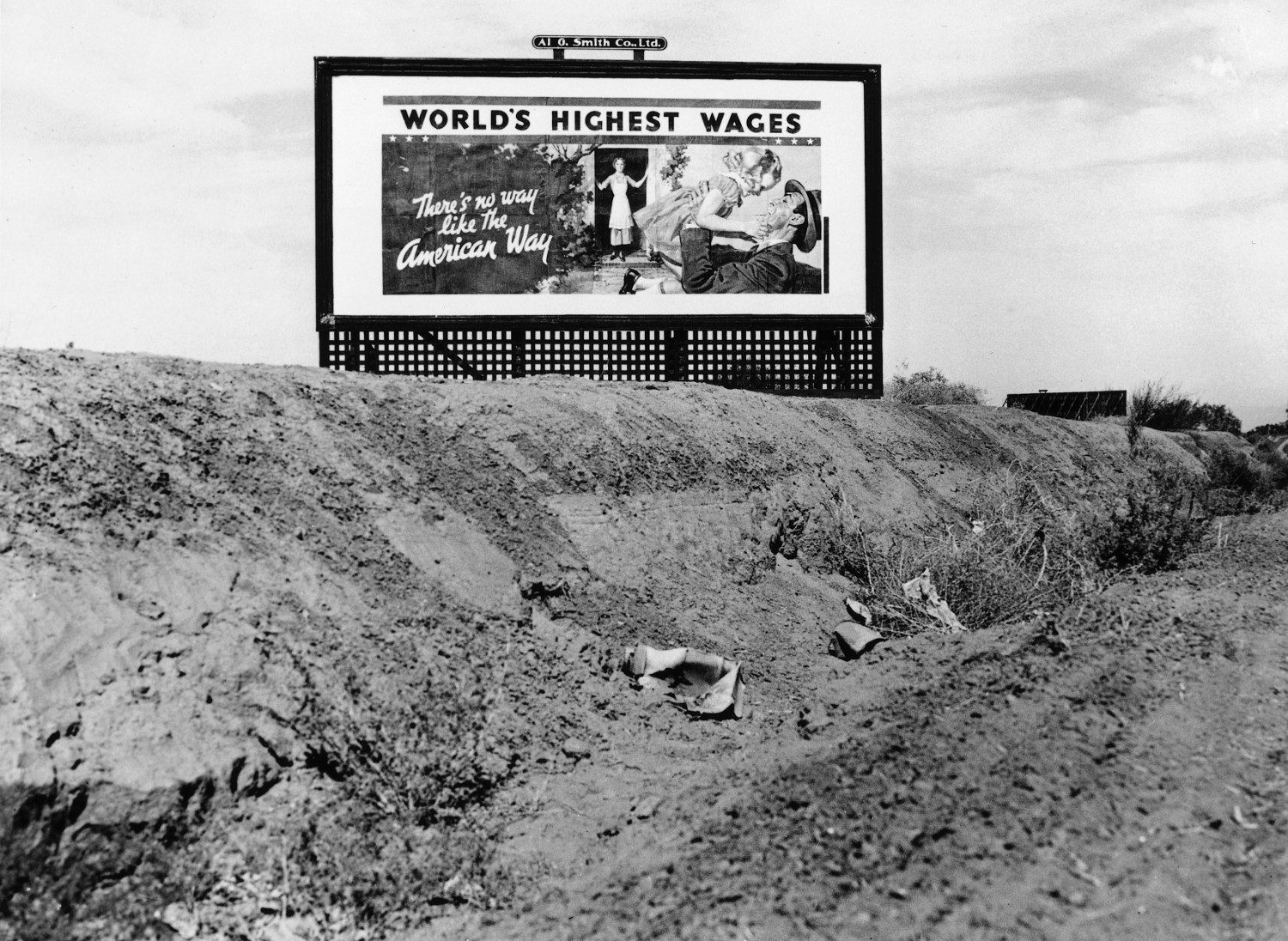

After a painful and lonely childhood marked by polio, Dorothea Lange took her first snapshots without a camera during her solitary walks in New York’s Lower East Side. She learned her trade as a portrait studio apprentice and took classes at the Clarence H. White School of Photography. When she met her first husband, painter Maynard Dixon, she was primarily inspired by western landscapes. In 1929, at the onset of the Great Depression, she had an epiphany: she had to focus on people. At the age of 40, she was hired by the history department of the Resettlement Administration, an organization that provided emergency relief to ruined rural families, and which in 1937 became the Farm Security Administration (FSA). Until 1942, this government agency implemented a massive project, halfway between documentation and propaganda, with the purpose of “introducing America to Americans” through photography. While her often reproduced images were becoming icons of the crisis (including the famous Migrant Mother from 1936—in reality a woman who had moved to California ten years earlier), the artist began taking her mission far more seriously.

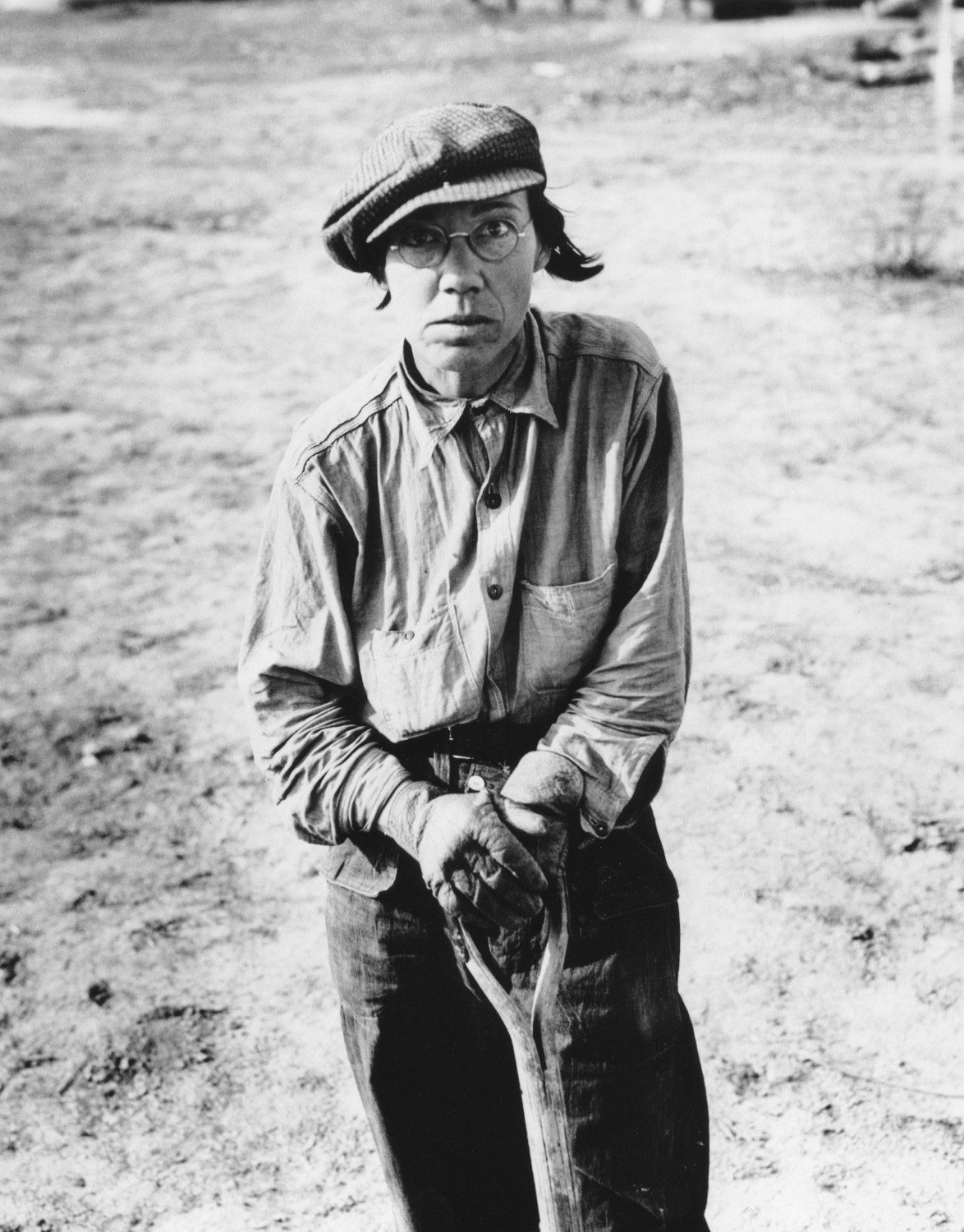

Her photographs of agricultural workers in Texas or Alabama, often shot from a low angle or even just above the ground, using wider angles, clearly sought to contextualize the individuals within their environment. Moreover, the photographer started providing increasingly detailed field notes along with the photographs. In 1941, she embarked on another governmental mission: photographing the resettlement and internment of Japanese Americans in California following Pearl Harbor. However, her images were too obviously critical to escape military censorship. In the 1950s, the “people’s photographer” accepted one of the first faculty positions in photography in San Francisco, and participated in the creation of Aperture Magazine. After her death, her images were exhibited, namely at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), and the Whitney Museum of American Art (1972).

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017