Eva Hesse

Lippard Lucy, Eva Hesse, New York, New York University Press, 1976

→Cooper Helen A, Berger Maurice, Eva Hesse: A Retrospective, New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery, 1992

→Corby Vanessa, Eva Hesse: Longing, Belonging and Displacement, London, I. B. Tauris, 2010

→Rosen Barry (ed.), Eva Hesse : exhibitions, 1972-2022 : reflections from sixteen curators, Zurich, Hauser & Wirth Publishers, 2024

Eva Hesse : a memorial exhibition, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 8 December 1972 – 11 February 1973

→Eva Hesse, Galerie nationale du Jeu de Paume, Paris, 27 April – 20 June 1993

→Eva Hesse, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, 12 February – 19 May 2002 ; Museum Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden, 15 June – 13 October 2002

American sculptor.

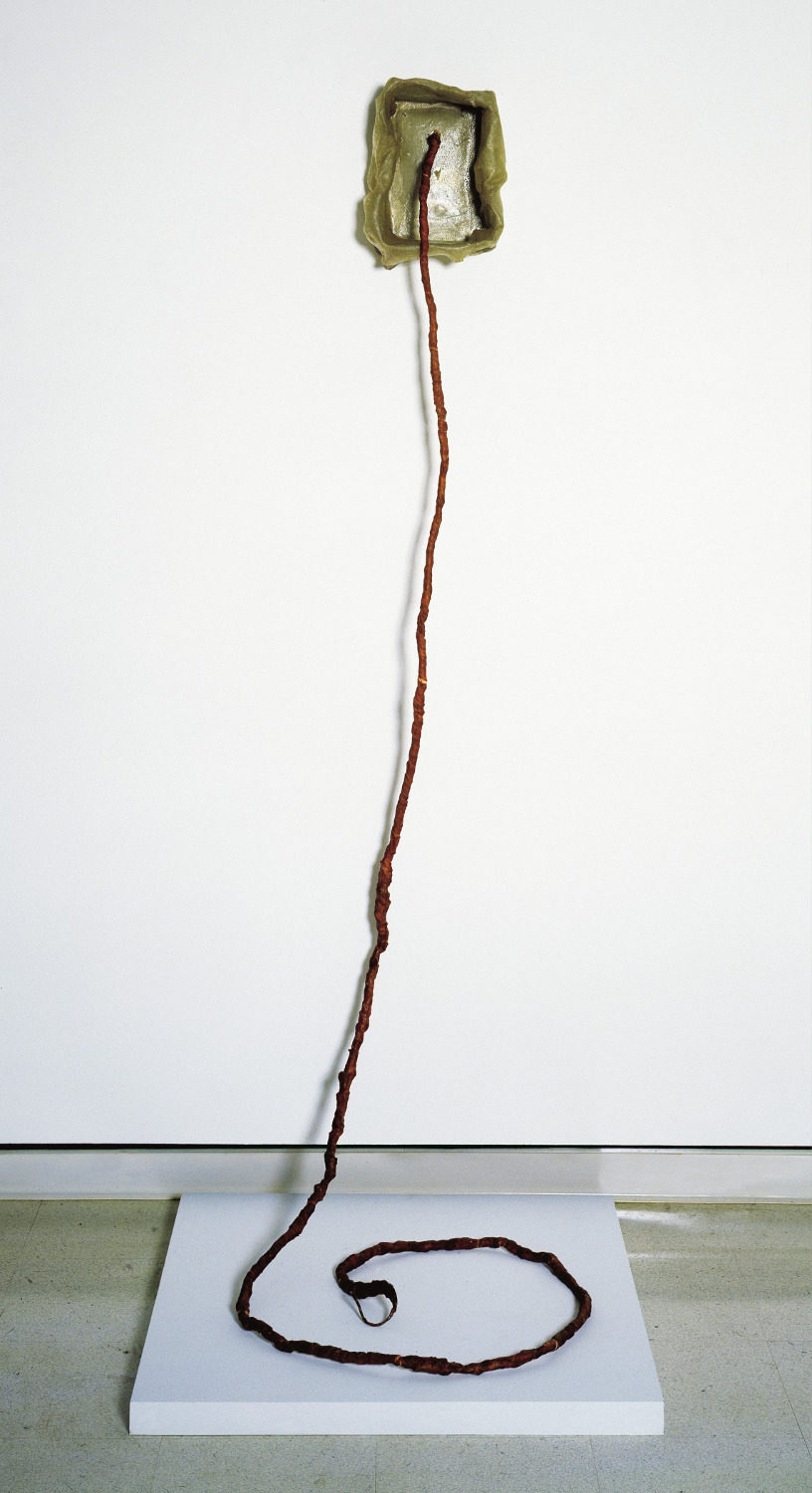

Born in Germany, Eva Hesse is associated with the postminimalist movement. Interpretation of her work, which had early on focused on her tragic, premature death, today centres on her formal innovations and the historically innovative aspects of her œuvre. Her childhood was marked by two closely linked dramas: her family’s exile to the United States in 1939, and the suicide of her mother in 1946. Her art studies began in 1952 at the Pratt Institute, followed by The Cooper Union, and lastly at Yale University, where she took a course on colour given by Josef Albers. In 2003 Linda Norden wrote that her earliest works – ghostly depictions – were a series of “introspective portraits”. In parallel to these figurative works, Hesse worked in an abstract style of painting and drawing, which she continued until her death. During her marriage to sculptor Tom Doyle from 1961 to 1966, she found it hard to combine her personal artistic development with her role as an artist’s wife in a predominantly male environment. In 1964-65, during a stay in Germany, she began working in three dimensions. Weary of her inability to fully express her creations on paper, she used ropes found in her studio to extend the lines in her drawings into space: this marked the start of her mature period (1965-1970). Her sculptures are closely related to minimal art, of which she adopted certain conventions, including repeating and adding forms, and opting for a human scale. However, to a greater degree than for her minimalist colleagues, she introduced psychology and the expression of the individuality of the artist into her works.

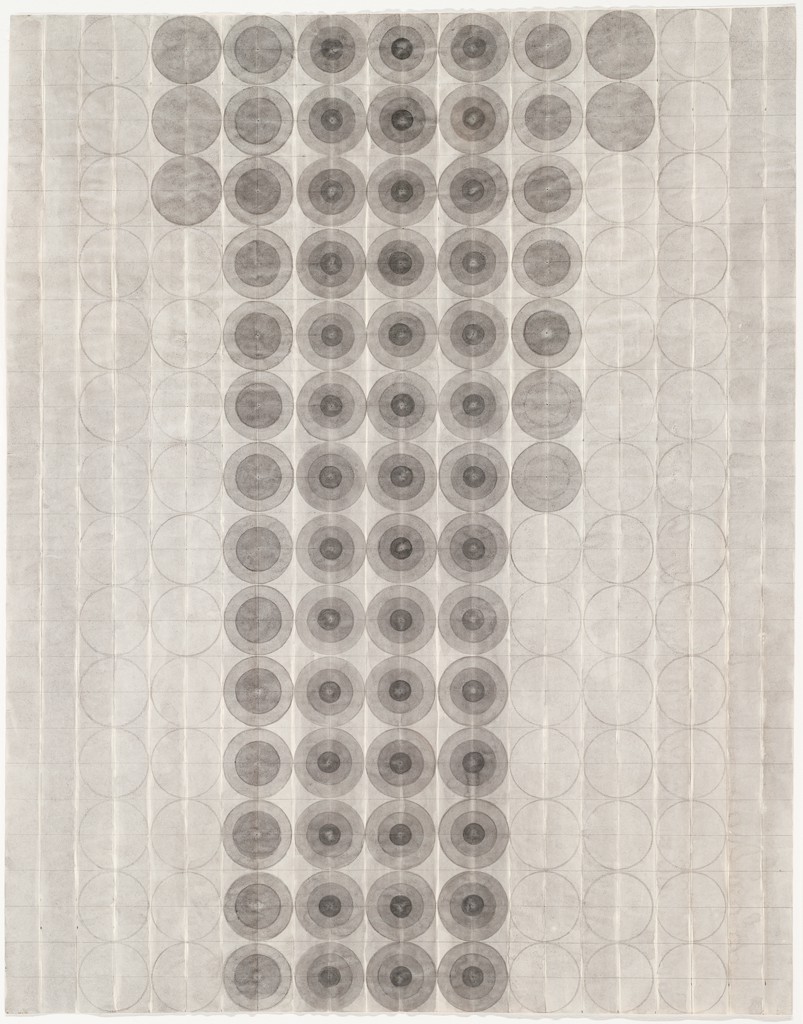

E. Hesse also restored themes like memory and sexuality into her art – topics that had been abandoned by minimalism – and incorporated her strong sense of the absurd, cultivating ambiguity and paradox. On this point, Yve-Alain Bois has stressed the twin forebears of Hesse’s art: minimalism, of course, but also neo-surrealism. Her use of flexible materials also recalls Robert Morris’ Anti Form. Three periods in her sculpted work can be discerned: the years 1965-66 were marked by explicit reference to the body, often with sexual undertones. Her early coloured reliefs gave way to mysterious objects made of papier mâché and string, such as Ingeminate (1965), in which twin, wrapped, phallic forms are bound together with a strange cord. In 1967-68 she began working on graphical matrices whose apparent precision belies an overall irregularity in their motifs.

This investigation of the grid extended into the third dimension, with the series Accession, which features minimalist cubes whose interiors are woven with an organic mass of rubber tubes. Lucy Lippard argued that this paradoxical combination was one of the characteristics of E. Hesse’s practice: hardness and softness, precision and chance, both geometric and free forms, and both force and fragility are some of her principles of construction. This period was also one of concentrated experimentation on unconventional materials, such as latex (from 1966) and fibreglass (from 1968). Like a paradoxical response to the sickness that would cause her death two years later, her sculptures became monumental, but did not lose their apparent fragility. Her key work at this time was Contingent (1969): it is 3.5m tall and 6.3m deep, and consists of eight vertical elements, made from cheesecloth and latex, set in a field of fibreglass. It was made with the help of assistants. A reflection of Hesse’s love of chance, the sculpture retains the irregularities that resulted from the fact that many people worked on it over a long period of time. During her lifetime, her work was included in important exhibitions, such as Harald Szeemann’s When Attitudes Become Forms in 1969. It was rediscovered during the 1980s and 1990s by a generation of artists moved by the psychological transformation of space and the exploration of alternatives to the militant feminism of the 1970s.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2018

Singular Visions: Eva Hesse, No Title, 1970

Singular Visions: Eva Hesse, No Title, 1970  About the exhibition "Eva Hesse 1965"

About the exhibition "Eva Hesse 1965"