Research

Carmen Herrera, Untitled, 1952, acrylic on canvas, 63.5 × 152.4 cm. Coll. MoMa, New York, gift of Agnes Gund and Tony Bechara

What you see is what you see” declared Frank Stella (1936-2024) of his work, neatly summing up one of the central characteristics of Minimal Art, in contrast with the Abstract Expressionism that preceded it. If we are to take this phrase literally, what “we see” is essentially the work of male artists. When F. Stella started work on his radical black striped paintings in 1959, however, the Cuban artist Carmen Herrera (1915-2022) had already been producing striped acrylics since the early 1950s.

Minimal Art has undeniably been historicised as masculine, a bias that is evident when we look at the creators chosen by art history to represent the movement: they are the omnipresent characters of the time, part of an art scene structured by a powerful patriarchy. The movement has been theorized mainly by men and not only by artists, such as Donald Judd (1928-1994) and Robert Morris (1931-2018). The term itself was introduced by Robert Wollheim in his article “Minimal Art”, published in Arts Magazine in 1965, in which he analyses this then-dominant artistic movement as a fundamentally reductionist form, resting on ideas of non-intervention as applied to the found object and the essentialism of monochrome inherited from two great male artists, Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) and Ad Reinhardt (1913-1967).

Yet one cannot deny that women artists and critics are also protagonists here. And, though the qualifier “minimal” has historically been favoured over “ABC Art”, the term put forward by Barbara Rose, several women artists represented the movement, both “in” and “off” the scene, from its very beginnings.

Anne Truitt: First New York Exhibition, André Emmerich Gallery, 41 East 57th Street, New York, © 2024 annetruitt.org

D. Judd, Clement Greenberg and Michael Fried praised the precocity of the minimal sculptural practice of Anne Truitt (1921-2004) on the occasion of her solo exhibition at André Emmerich Gallery, New York in 1963. A. Truitt was one of three women among the forty-two artists presented at the founding exhibition of the movement, Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculptors, at New York’s Jewish Museum from April to June 1966. She appeared alongside Judy Chicago (née Judy Cohen, 1939) and Tina Matkovic Spiro (b. 1943), who had previously participated in the Seven Sculptors exhibition at Philadelphia’s ICA in December 1965, also with A. Truitt. Later that same year, Agnès Martin (1912-2004) and Jo Baer (b. 1929) would present work as part of the Systemic Painting exhibition at the Solomon Guggenheim Museum, another of the movement’s landmark events. J. Baer had been part of Eleven Artists, organised by Dan Flavin (1933-1996) in 1964. In 1968 Mary Corse (b. 1945), an artist linked to the Californian Light and Space movement, began to mix her acrylic paint with glass microspheres, an industrial material used for road signs, resulting in paintings that seem to glow with their own inner light. Beyond the world of the visual arts, certain choreographers and dancers were likewise creating pioneering work: Anna Halprin, searching for a purity of movement, unleashed dance from narrative and expression, in turn influencing her students Yvonne Rainer and Simone Forti; Lucinda Childs and Deborah Hay would also worked from this pared-back perspective.

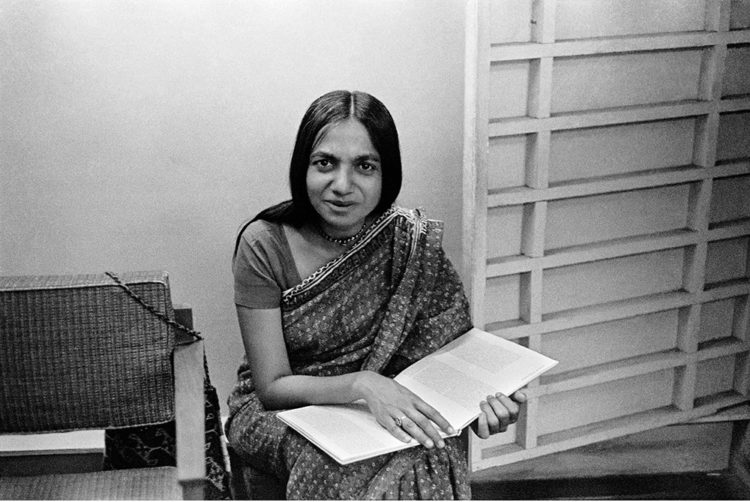

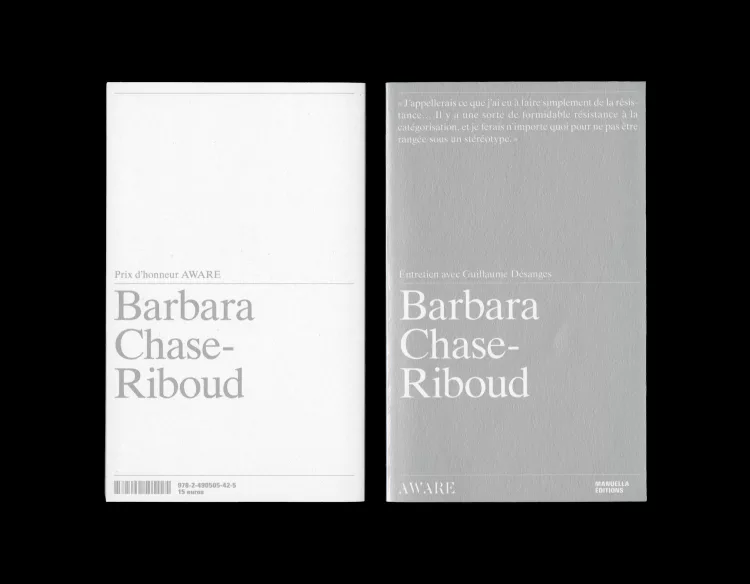

The artists cited here are those who are commonly listed in general publications dedicated to Minimal Art and at first glance seem to constitute its circle of women. Their works are founded on certain typical elements of the movement: pure geometric form, seriality, a desire to rid the work of expression and personal emotion. Perhaps it goes without saying that none of them enjoyed a career comparable to their male counterparts. Other artists were later the subjects of studies and posthumous exhibitions,1 including Dorothea Rockburne (b. 1932), Mia Westerlund Roosen (b. 1942), Jackie Ferrara (b. 1929), Rosemarie Castoro (1939-2015), Lydia Okumura (b. 1948), Noemí Escandell (1942-2019), Gego (1912-1994), Mildred Thompson (1936-2003), Barbara Chase-Riboud (b. 1939), Mary Obering (1937-2022), Zilia Sánchez (b. 1926), Nasreen Mohamedi (1937-1990), Kazuko Miyamoto (b. 1942), Senga Nengudi (b. 1943) and Maren Hassinger (b. 1947), along with Europeans such as Marthe Wéry (1930-2005), Charlotte Posenenske (1930-1985) and Magdalena Więcek (1924-2008), but this list is by no means an exhaustive list. And not all of these artists are generally associated with Minimal Art, since the label, with its intransigent, limited vision, quickly became restrictive.

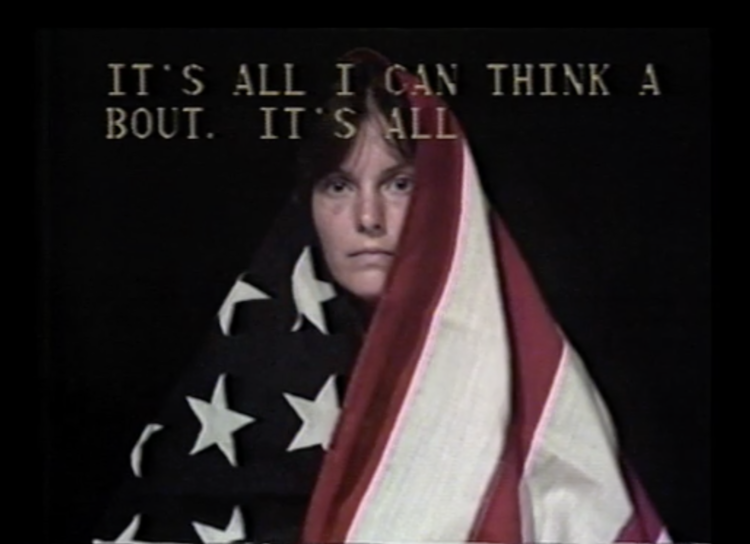

The feminist consciousness that developed in the early 1970s highlighted the rhetoric of power embodied by the Minimal movement, which was already being accused of symbolising American imperialism and capitalism.2 Seeking to break from this, post-minimalism turned its attention to irregular structures, the handmade and organic metaphor, evoked by flexible industrial products such as fibreglass, latex and hemp, materials used by Eva Hesse (1936-1970), Lynda Benglis (b. 1941) and Jackie Winsor (1941-2024).3 The exhibition Eccentric Abstraction, later considered the first of the post-minimalist movement, was held at Fischbach Gallery in New York in 1966, just a few months after Primary Structures,4 proposing a more intuitive approach. Women artists, having experienced the subjugating effects of an invisibilising male hegemony, tended towards a porous language as an alternative to orthodoxy, the symbol of a dominant power. This pluralistic vision began to supplant its monolithic predecessor, and the enthusiasm for technological and industrial progress waned. At the beginning of the 1970s the techno-optimism that Minimal Art evoked seemed not only old-fashioned but morally reprehensible from a feminist perspective.5 Lucy Lippard even celebrated the retreat of Modernism’s formalist ideology, at once a symbol of the patriarchy and of a neutralised, dehumanised art, as a feminist contribution to the culture.6

After the 1960s, the women artists who continued to explore Modernist and Minimal language by challenging it were neglected by the establishment, and simultaneously suffered from the distancing of feminist concerns.

Beverly Pepper checking out the installation of her sculpture at Albright-Knox’s Sculpture Garden in 1969, Courtesy Albright-Knox Gallery Digital Assets and Archives Collections, Buffalo, New York

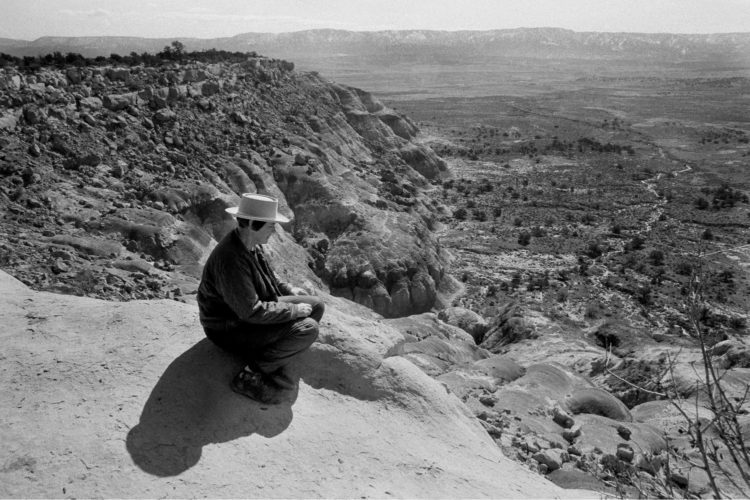

If, looking to sculpture, we exclude those works considered post-minimal, we are left with few examples and rare case studies. With its reduced geometric forms, modular structure, use of industrial materials, focus on anonymity and, as A. Truitt put it, desire “to get maximum meaning in the simplest possible form”,7 this kind of sculpture seems to have found few practitioners among women, employing as it does a language considered fundamentally phallocentric. Works in metal in particular, often monumental and thus deemed too physically demanding for the female gender, have often been considered the preserve of men. Richard Serra (1938-2024), Anthony Caro (1924-2013) and Mark di Suvero (b. 1933) occupy a significant space in the field, both literally and figuratively, while women sculptors creating large-scale metal works are relatively unknown. Which is not to say that many of them do not excel in the medium. This analysis, unable to enumerate them all, is based on certain artists active in the United States between 1960 and 1980, and in particular those who, attracted by the materiality of the medium and its resistance to the elements, became interested in the public space, and through this modified their approach to austerity of form.

Perhaps the most well-known of these figures is Beverly Pepper (1922-2020), hailed early in her career by Rosalind Krauss. She began to create her monumental metal sculptures in 1962 with works in the streets of Spoleto, a town in Umbria, supported by Italian steelworks company Italsider, meaning that she was able to work directly with the factory. Her work within the metallurgical industry meant that she was one of the first artists to experiment with Corten steel, as early as 1964, even before R. Serra.8 She started by producing chains of repeat geometric shapes, and inspired by ancient art, went on to create a series of totemic pieces and urban altars.

Like Doris Chase (1923-2008), Lila Katzen (1925-1998) and Anita Margrill (b. 1937) among others, B. Pepper would reflect deeply on the place of sculpture in the urban space, its inclusion in the social sphere raising cultural and ideological questions that mirrored political movements of the time.9 Her aim was to establish a direct relationship with the public through sculptures to be placed on the ground, without a pedestal, with the intention of energising a landscape, instilling a sense of community spirit, broadening perspectives. These sculptors proved sensitive to the ordinary visitor’s perceptions, to the experience of sculpture beyond the walls of the “white cube”, as well as to interventions in landscape – a trend common to a number of artists at the time, including Nancy Holt (1938-2014), Alice Adams (b. 1930), Mary Miss (b. 1944), Alice Aycock (b. 1946) and Meg Webster (b. 1944). Playing with visual clarity and complexity of form, these artists do not display Minimal Art’s hostility to the symbolic or the emotional. The referential nature of the work is fundamental in order to give the spectator a precise spatial and temporal perception without losing sight of reality. The “specific object”, isolated, authoritarian, impenetrable and self-referential, gives way to a subjectivity that is dialectically articulated by its relation to others, in an ongoing negotiated exchange. The distance the artists have taken from the orthodoxy of Minimalism has often led to them being characterised as abstract, geometric or post-constructivist, which mistakenly emphasises their links to Modernism.

Jane Manus, Delta One, 1979, 120 × 120 × 120 m, Welded Corten Steel, Collection of Mississippi Museum, Jackson, Mississippi

Linda Howard (b. 1934) is best known for her geometric open-air sculptures constructed from square aluminium tubing. Through her work she explores the relationship between mathematics and nature, the paradox between experienced reality and knowledge, between physical and conceptual reality, as we can see in Round About (1976). Her sculptures, geometric and extremely purified, play with contradiction – oppositions of open/closed, straight/curved, organic/inorganic. Jane Manus (b. 1951) is also interested in irregularity as a research topic. A graduate of the Art Institute of Boston, she started to create symmetrical volumes from welded Corten steel there in the mid 1970s. During the period, she produced her initial paradoxical structures, founded on precarious equilibriums, such as her first monumental piece Delta One (1979). Moving in Florida in the 1980s, she began working on the more flexible material of aluminium, continuing to interrogate the notion of imbalance. Lines keep escaping without ever finalising their form, in Girls Night Out (1984), Broken Open (1986) and Stand Alone (2020). These works offer up multiple perceptions and readings depending on the viewer’s perspective, and never seem fully finalised or entirely satisfactory. They confront us with their unexpected deviations, and their narrative titles often appear to deepen their narrative titles support this unpredictability that belongs to the real experience. The titles evoke a figure or a situation, and thus dispel the enigmatic character that abstract forms can suggest. Though she often favours primary colours, J. Manus also deploys oranges and golds, allowing the forms to interact more freely with their environment.Without making any secret of their fascination with Modernism, these sculptors distance themselves from a fixed Minimalist dogma, preferring instead to express mutability. Thanks to the wide range of formal possibilities that this approach opens up, they prove to be rich sources as part of the evolution of the Minimal Art movement.

Notably the following exhibitions: Other Primary Structures, organised by Jens Hoffmann, Jewish Museum, New York, 2014; We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women 1965-1985, organised by Catherine Morris and Rujeko Hockley, Brooklyn Museum, New York, 21 April-17 September 2017; Magnetic Fields: Expanding American Abstraction 1960s to Today, organised by Erin Dziedzic and Melissa Messina, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, 13 October 2017-21 January 2018;Land of Lads Land of Lashes. Rosemarie Castoro, Wanda Czelkowska, Lydia Okumura, organised by Anke Kempes, Thaddaeus Ropac, London, 25 June-10 August 2018; Figures on a Ground, organised by Éléonore de Sadeleer and Evelyn Simons, Cab Foundation, Brussels, 10 June-1 December 2020; Female Minimal: Abstraction in the Expanded Field, organised by Anke Kempkes, London, Thaddaeus Ropac, Autumn 2020.

2

See James Meyer, Minimalism: Art and Polemics in the Sixties (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003).

3

The term “post-minimalism” was first used by Robert Pincus-Witten in an article devoted to Eva Hesse: “Eva Hesse: Post-Minimalism into Sublime”, Artforum 10, no. 3 (November 1971). For its definition, see Robert Pincus-Witten, Postminimalism(New York: Out of London Press, 1977).

4

Eccentric Abstraction, curated by Lucy Lippard, opened in September while Primary Structures took place between April and June. The exhibition was thus contemporary with Systemic Painting. The theory of a feminine and feminist differentiation was notably expressed in one of the first exhibitions to pay homage to a women’s post-minimalism, Sense and Sensibility: Women Artists and Minimalism in the Nineties, organised by Lynn Zelevansky at MoMa in New York from 16 June to 11 September 1994. Concerning the expression of masculinity and domination in Minimal Art, see Anna Chave, “Minimalism and the Rhetoric of Power”, Arts Magazine 64, no. 5 (January 1990): pp. 44-63.

5

See Susan L. Stoops “From Eccentric to Sensuous Abstraction: An Interview with Lucy Lippard”, in More than Minimal. Abstraction in the ’70s (exhib. cat. Waltham: Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University), pp. 28-31 and Susanneh Bieber, “Technology, Engineering, and Feminism: The Hidden Depths of Judy Chicago’s Minimal Art”, Art Journal 80, no. 1 (March 2021): pp. 106-123.

6

Lucy Lippard, “Sweeping Exchanges: The Contribution of Feminism to the Art of the 1970s”, Art Journal 40, nos 1-2 (Autumn-Winter 1980): pp. 362-365.

7

Anne Truitt’s full quotation runs as follows: “I have never allowed myself, in my own hearing, to be called a Minimalist. Because Minimalist art is characterised by nonreferentiality. And that’s not what I am characterised by. [My work] is totally referential. I’ve struggled all my life to get maximum meaning in the simplest possible form” (1987).

8

See Sarah Cascone, “At 96, the Sculptor Beverly Pepper Is Only Now Getting Credit for Using Cor-Ten Steel Way Before Richard Serra”, Artnet, 24 February 2019.

9

See Helen A. Fielding, Cultivating Perception Through Artworks: Phenomenological Enactments of Ethics, Politics and Culture (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2021).

Annalisa Rimmaudo is a curator in the Department of Contemporary Collections at the Musée National d’Art Moderne – Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, and is President of the Christian Boltanski Endowment Fund. She holds a doctorate in Contemporary Art History from the Université Paris-Sorbonne and is and exhibition curator, researcher, and the author of numerous publications and has spoken at several symposiums. She is a member of the editorial board of Aware Archives for Women Artists Research & Exhibitions.

Annalisa Rimmaudo, "Minimal and Post-Minimal: Sculpture Beyond the White Cube." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/minimales-et-post-minimales-la-sculpture-hors-du-white-cube/. Accessed 12 July 2025