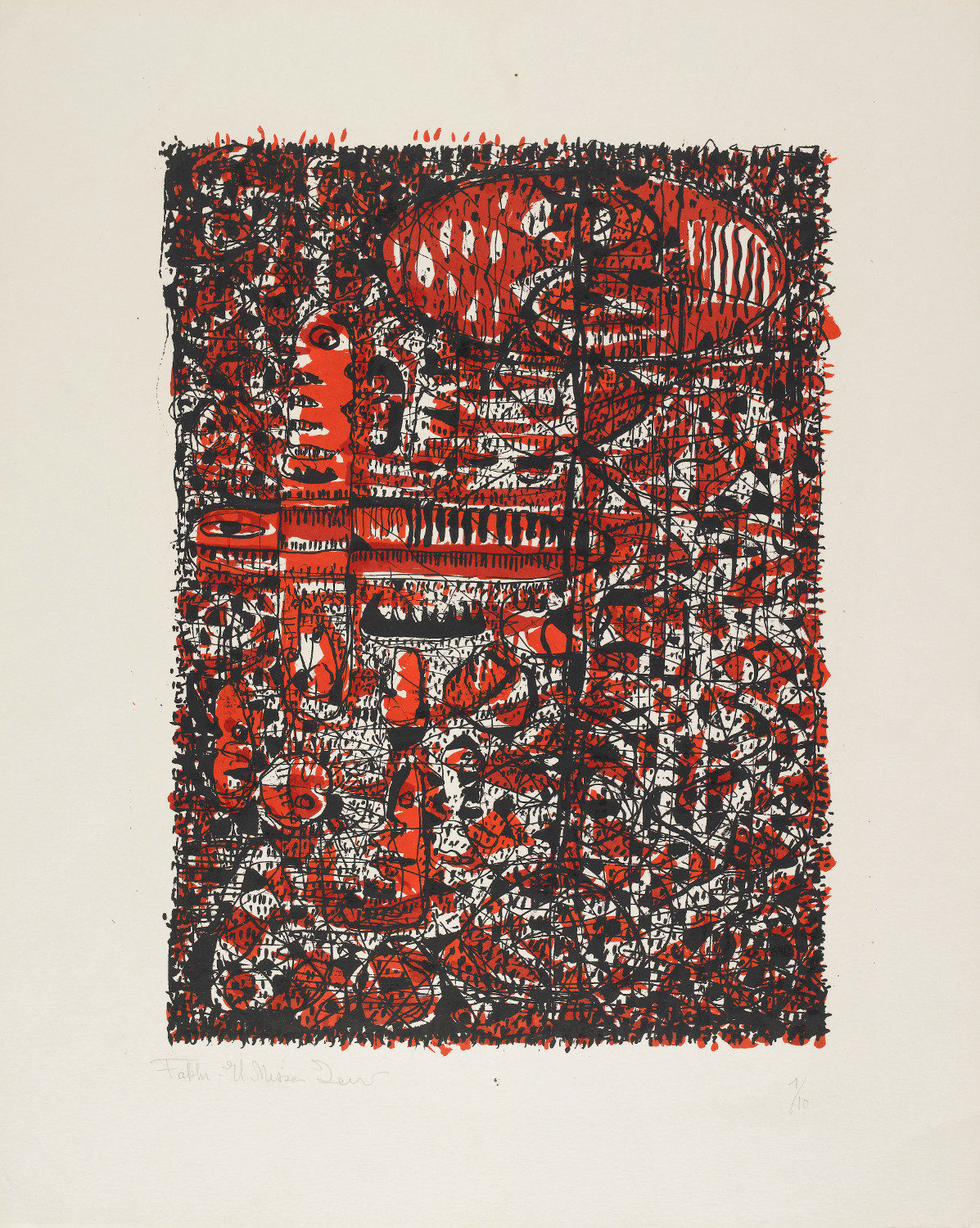

Fahrelnissa Zeid

Laidi-Hanieh Adila, Fahrelnissa Zeid: painter of inner worlds, London, Art / Books, 2017

Fahrelnissa Zeid, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 1954

→Fahrelnissa Zeid, Tate Modern, London, 13 June – 8 October 2017

Turkish-Jordanian painter.

Born into an intellectual Ottoman family, the young Fahrinnisa Shakir Kabaağaçli was among the first women pupils at the Istanbul Women’s Beaux Arts Academy in 1919. In the 1920s, she travelled throughout Europe, visiting museums and making copious sketches, which she annotated extensively. A turning point was her 1928 enrolment at the Académie Ranson in Montparnasse, where she studied under cubist painter Roger Bissière. Upon her return to Istanbul, she abandoned her academic figurative practice and turned towards modernism and expressionism, painting in a studio in her home. In 1933, she married Iraqi diplomat Prince Zeid Al-Hussein and arabicized her name. The following decade was one of health breakdowns, short stays in Baghdad and Budapest, as well as a three-year stint in Berlin. She visited museums extensively and took painting tuition. Throughout this period, her doctors urged Fahrelnissa Zeid to paint. In 1941, she became the only Turkish female member of the Avant-garde art group D Grubu. She exhibited with them before exhibiting alone to great acclaim from 1945.

In 1946, she left for London, where she held a number of exhibitions. In 1948, she turned to abstraction (Composition, 1950), and met Charles Estienne at her first Paris solo exhibition, in 1949. He integrated her into the constellation of artists working in lyrical abstraction whom he promoted, and she became a prominent member of the Nouvelle École de Paris from its beginnings. She exhibited often with its artists as well as at the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles. Her Paris career was bolstered also by notable female gallerists developing abstract art recognition: Colette Allendy, Dina Vierny and Katia Granoff. In London, F. Zeid became in 1954 the first female artist to have a solo exhibition at the prestigious Institute of Contemporary Arts. Her work was praised by critics of the period as varied as André Breton, George Butcher, Bernard Gheerbrant, Terence Mullaly, etc. She recognized in Vassily Kandinsky’s writings a starting point for an articulation of her views, especially his conceptions of abstract composition, and painting as an “inner necessity.”

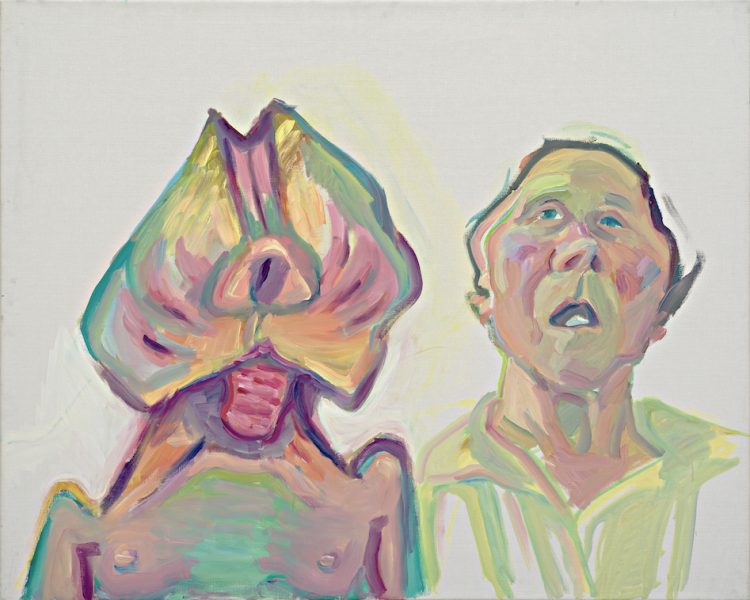

After the 1958 coup in Iraq, Fahrelnissa Zeid lived in exile between Paris, London and Ischia, until 1975, when she moved to Amman to join her son, who lived there, and began teaching art. In the 1960s, she returned to figuration via portraiture (Portrait de Charles Estienne, 1964), while inventing and developing a unique art form, coloured polyester and resin blocs encasing painted animal bones that she called Paléokrystalos and set on revolving stands, back lit with colour projectors, which she developed after her prototypes were appreciated by André Malraux. Her seminal 1981 group exhibition, which she held with her students, contributed to the normalization of abstraction in Jordan. Turkish-Jordanian modernist Fahrelnissa Zeid was the first Middle Eastern artist to conduct a career recognized at home as well as in international art centres. Despite her privileged background, she contended with personal tragedy and turmoil, and prejudice about her gender and her non-western origins to chart a unique path and become a major twentieth-century modernist.

Fahrelnissa Zeid – 'She Was the East and the West'

Fahrelnissa Zeid – 'She Was the East and the West'