Research

When considering Japanese women painters who moved across borders, those familiar with Japanese contemporary art will probably answer Yayoi Kusama (b. 1929), who moved to the United States in 1957, or Yoko Ono (b. 1939), who moved to the United States with her family in the 1950s. These artists are well known for their careers, which began following World War II.

But what about earlier periods? Were Japanese women artists confined to Japan?

Historically, few Japanese women painters ventured abroad. Notable exceptions include Rin Yamashita (1857-1939), who studied icon painting in Russia in 1880, and Fujio Yoshida (1887-1987), who travelled to the USA in 1903 at the age of 16 with her future husband, Hiroshi.

This essay focuses on three Japanese women painters — Haruko Hasegawa (1895–1967), Toshiko Akamatsu (later Toshi Maruki, 1912–2000) and Mitsuko Arai (later Mitsu Yashima, 1908–1988) — who were active during the 1930s and 1940s. Each of these artists experienced transnational migration and lived through the tumultuous war years.1

The first of these painters, Haruko Hasegawa,2 studied in France before joining the Japanese Army, serving in Manchuria and China. Near the end of the war, she founded the Women Artists’ Public Service Brigade, an aid association. The second, Toshiko Akamatsu,3 travelled to the Palau Islands and Yap Island in the South Sea archipelago, then under Japanese control, and made several trips to the Soviet Union. The last, Mitsuko Arai,4 fled to the USA after facing severe repression for her involvement in the pre-war proletarian art movement, and lived there the rest of her life.

Despite their differing activities and perspectives on the war, these three artists shared a dynamic geographic mobility and a commitment to their artistic expression, despite the challenges posed by their dual identities as women and painters. Their careers as artists disrupted the prevailing gender norms of the time.

In Japan, the 1920s and 1930s were a vibrant period for art. After World War I, popular culture grew in the cities, bringing about changes in lifestyles and cultural norms. The women’s suffrage movement gained momentum, and new professions for women emerged, such as ‘bus girls’ and telephone operators. What began as modern culture in the 1920s had evolved into consumer-driven culture by the 1930s. Although the Japanese economy struggled due to the Great Depression, it rebounded after the Manchurian Incident in 1931. However, this economic recovery was accompanied by a rise in fascist politics, leading to an extended period of war.

At the time, women faced exclusion and marginalization in both the art world and art education.5 Until 1946, women were barred from attending the Tokyo Fine Arts School (founded in 1887, now the Tokyo University of the Arts), which was considered the top art institution in Japan. Women could only study art at the Women’s School of Fine Arts (Joshi Bijutsu Gakkō, now Joshibi University of Art and Design), other specialised institutions, or through private study. Women artists were expected to focus on ‘feminine’ subjects such as flowers and children and were discouraged from exploring self-portraits or outdoor landscapes. For a woman to become a painter required her to come from an upper-middle-class family that could afford a good education and to have supportive parents. All three women discussed here were from such backgrounds and had the advantage of parental support and a conducive cultural environment. However, their careers were often overshadowed by their husbands’ achievements, and they became marginalised when they changed their family names after marriage or moved abroad.

Portrait of Haruko Hasegawa in Hanoi, 1939

Haruko Hasegawa, Helene and Paris, 1936-37, oil on canvas, Ⓒ editorial republica collection, Tokyo, 2024

Haruko Hasegawa, Native Customs in South China, 1939, water color, Private Collection

Haruko Hasegawa: to the battlefield with the Japanese Army

In the 1930s, H. Hasegawa distinguished herself by frequently travelling abroad and establishing herself within a broad network of artists, notably by founding several associations for women painters. Born in Tokyo in 1895, H. Hasegawa began her artistic training after graduating from a girls’ school, studying Japanese-style painting (nihonga) under Kiyokata Kaburaki (1878–1972) and Western-style painting (yōga) under Ryuzaburo Umehara (1888–1986). In 1929, she travelled to France, a country she longed to visit, where, influenced by Tsuguharu Foujita (Léonard Foujita, 1886–1968), she had two solo exhibitions in Paris. This gave H. Hasegawa many opportunities to travel abroad. Her journey back to Japan in 1931 included crossing the Soviet Union on the Trans-Siberian Railway. Upon her return, she witnessed Japan’s establishment of a puppet government in Manchuria and recognised the broader implications of the country’s expansionist policies. At the same time, she felt disappointed by what she saw as France’s ‘old-fashioned’ nature. This ambivalence drove H. Hasegawa to become more openly involved in Japanese nationalism and war efforts.

Later, H. Hasegawa served with the Japanese Army in Manchuria, southern China and Hainan Island, where she painted war pictures. In 1939, she even travelled to Hanoi, then under French military rule and a hotbed of political tension after the majority of Japanese inhabitants had been repatriated. Her account of her visit, The Virgin Soil of the South (1940),6 offered a colonial perspective, depicting Vietnam as a ‘sleeping, dormant virgin’, and included essays and illustrations that expressed sympathy for local women and criticism of the French authorities. As the Asia-Pacific War neared its end, H. Hasegawa remained in Japan and organised the Women Artists’ Public Service Brigade in 1943 to support the war effort on the home front.

Toshiko Akamatsu, Sketch of Moscow No. 75, (Russian Kitchen), 1937, water color

Toshiko Akamatsu, Moscow’s Four Seasons (Thawing Season), 1944, oil on canvas, Private Collection

Toshiko Akamatsu, Yap Island, 1940, oil on canvas, 60.6×72.7 cm, Private Collection

Toshiko Akamatsu (Toshi Maruki): to the Soviet Union and the South Seas

Although T. Akamatsu was part of the Women Artists’ Public Service Brigade, she was not a particularly enthusiastic member. Born in 1912 in Hokkaido, Japan, to a father who was a temple priest, she studied oil painting at the Women’s School of Fine Arts. In her 20s, she was assigned to Moscow as a home tutor for the children of Japanese interpreters and the Moscow Minister, spending time there in 1937 and 1941. There, she was able to engage with artworks that had been previously difficult for her to access.

In 1940, inspired by her admiration for Paul Gauguin, T. Akamatsu also spent six months travelling to the Palau Islands and Yap Island in the South Sea archipelago, then under Japanese rule. During this period, she created many sketches and oil paintings, depicting local traditions and daily life. These works contributed to the propaganda supporting Japan’s Southern Expansion Doctrine.

T. Akamatsu’s time in Moscow, where she sketched intensively, and in the South Seas, where she added rich colours and nudes into her art, pushed her to explore beyond the conventional frameworks of ‘Japanese’ and ‘Western’ painting. This exploration laid the groundwork for her later collaboration with her husband, Iri Maruki, on The Hiroshima Panels.

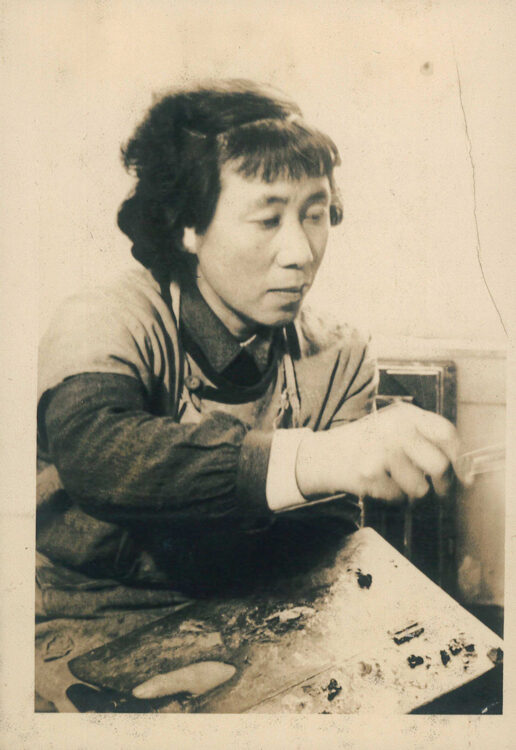

Mitsuko Arai in San Francisco, 1975, all rights reserved

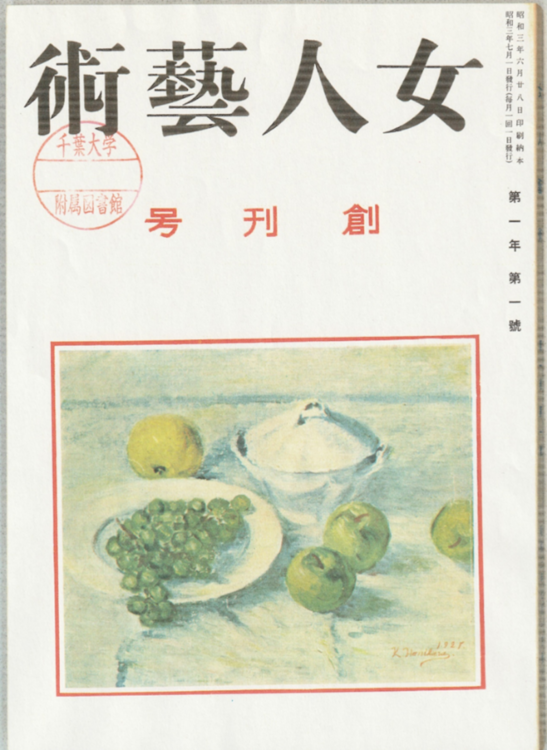

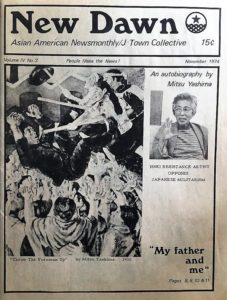

Mitsu Yashima, Dou Age, as the cover of New Dawn: Asian American News monthly /J-Town Collective (November 1974)

Mitsuko Arai (Mitsu Yashima): spending their latter half of their lives in America

Born into a Christian family in 1908 to a father who worked for a shipbuilding company, M. Arai grew up in a comfortable household. After graduating from Kobe College in 1926, she moved to Tokyo to study art at Bunka Gakuin. There, she was introduced to socialism and joined the Japanese League of Proletarian Artists (Nihon Proletaria Bijutsuka Dōmei) and began depicting the struggles of peasants and workers.

The proletarian art movement, active from the 1920s to the early 1930s, was based on socialist and communist ideals but was heavily repressed. In 1933, a pregnant M. Arai and her husband Jun Iwamatsu (later Taro Yashima) were arrested. Even after their release, they were closely monitored by the Special Higher Police. In 1939, fearing for their safety, they fled to the United States, adopting the names Mitsu and Taro Yashima. In the USA, M. Arai’s husband became a successful children’s book author.

To support her family during difficult times, M. Arai took on various side jobs and endured her husband’s domestic abuse for many years. In 1968, when their daughter reached adulthood, M. Arai left her husband and moved from Los Angeles to San Francisco. There, she began a new life teaching painting and participating in the anti-Vietnam War movement. M. Arai played a role in bridging the first-generation and third-generation Japanese American communities and appeared in a film about the Manzanar internment camp.7 She spent her later years dividing her time between New York and the West Coast before passing away at the age of 80. Recently, her transnational life and artwork straddling Japan and the USA have attracted renewed interest.8

During the 1930s as Japan headed towards war, artists such as M. Arai, T. Akamatsu and H. Hasegawa each contributed to the art world in their own ways, despite their differing ideologies. Although they were from upper-middle-class backgrounds and had access to art education, their careers were often overshadowed or neglected due to their gender and they had to live within a structure where this exclusion was tied to the authority of organisations and institutions.

After Japan’s defeat in World War II, M. Arai moved to the USA to escape oppression by the Japanese police and continue her art practice. In contrast, towards the end of the war, H. Hasegawa stayed in Japan, shifting her focus from the front lines of battle to supporting the war effort on the home front. During her wartime travels to Moscow and the South Sea archipelago, T. Akamatsu developed an artistic style that would shape her post-war work, notably in The Hiroshima Panels. The transnational experiences and artworks of these three artists offer rich opportunities for reinterpreting art history and challenge existing research that often isolates women’s contributions into niche categories.

Tomoko Kira, Women Painters and the War [Josei gakatachi to sensō] Tokyo; Heibonsha, 2023: Megumi Kitahara, “Wartime Women Painters Crossing Borders: Haruko Hasegawa, Fumie Taniguchi, and Mitsuko Arai”, Journal of Gender Studies, Tokyo; Ochanomizu University, 2022, pp. 65-84.

2

Megumi Kitahara, “Artist Haruko Hasegawa during the war”; Reiko Kokatsu, “What did Japanese women painters depict during the war?”, both in How Asian Women’s Bodies Were Described: Visual Representations and Memories of War, Tokyo; Seikyu-sha, 2013.

3

Toshi Maruki Centennial Exhibition: Moscow, Palau and the Hiroshima Panels, Ichinomiya City Memorial Art Museum, 2012.

4

Megumi Kitahara, “Mitsuko Arai (Mitsu Yashima) (1): A Woman Artist Who Participated in the Proletarian Art Movement in the Early Showa Period”, Machikaneyama Ronso (Japanese Studies), Osaka University, 2021, pp.1-30.; Sho Usami, Goodbye Japan: Picture book artists Taro Yashima and Mitsuko’s exile, Tokyo, Shobun-sha, 1981.

5

Reiko Kokatsu, “Japanese Women Artists, their Position and Politics: mainly Oil Painting Artists before and after World War II”, Japanese Women Artists before and after World War II, 1930s-1950s, Tochigi Prefectural Museum of Fine Arts, 2001.

6

7

TV Movie, Farewell to Manzanar, directed by John Korty, National Broadcasting Corporation, 1976.

8

Valerie Matsumoto, “‘A Living Artist with Open Eyes’: the Transnational Journey of Mitsu Yashima”, ADVA (Asian Diasporic Visual Cultures and the Americas), 6 (1-2) Brill, 2020.

Megumi Kitahara, is professor Emerita in Osaka University.

She finished the doctoral course in Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (Culture and Representation) at Tokyo University (Ph.D). She has continued working on an in-depth analysis of the visual information surrounding daily life, primarily from the perspectives of gender, sexuality, ethnicity, race, and class. She has contributed a serial article “Art activism” since 1994, studying the representation of war and histories of women artists in Japan. Her major works include; Art Activism (Impact Publishing Association, 1999); Disrupting Molecules @Borderlines (Impact Publishing Association, 2000); How have been described Asian Women’s Bodies (Seikyu-sha Publishing, 2013).

She has a home page to study visual representations such as art from the perspectives of gender, race, and postcolonialism; http://www.genderart.jp/

Megumi Kitahara , "The Japanese women painters who moved across borders in the 1930s and 40s, and during World War II." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/femmes-peintres-japonaises-qui-voyagent-hors-des-frontieres-ou-sexpatrient-vivre-dans-les-annees-1930-1940-en-temps-de-guerre/. Accessed 3 July 2025