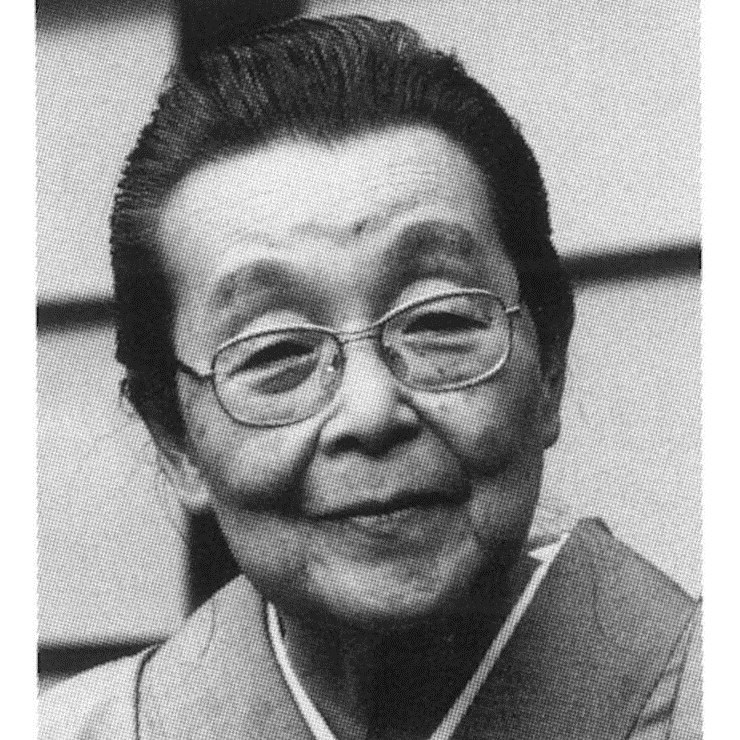

GUAN Zilan (Violet Kwan)

Andrews, Julia F., “Women Artists in Twentieth-Century China: A Prehistory of the Contemporary,” in positions vol. 28, no.1, 2020

→Wangwright, Amanda, The Golden Key: Modern Women Artists and Gender Negotiations in Republican China (1911-1949), Leiden, Brill, 2020

→Pickowicz, Paul G., Shen Kuiyi, and Yingjin Zhang (eds.), Liangyou: Kaleidoscopic Modernity and the Shanghai Global Metropolis, 1926–1945, Leiden, Brill, 2013

Her Narrative: A Female Perspective of GDMoA Collection, Guangdong Museum of Art, Guangzhou, August, 2021

→Self Image: Woman Art in China (1920-2010), CAFA Museum, Beijing, December 2010-February 2011

→Shanghai Modern, Museum Villa Stuck and the Shanghai Municipal Administration of Culture, Radio, Film, & TV, Munich, October 14, 2004-January 16, 2005

Chinese painter.

Because of her parents’ interest in art – both worked as fabric designers in the textile industry – Guan Zilan received training in the arts from an early age. After studying painting at the Shanghai Shenzhou Girls’ School, Guan enrolled at the Chinese University of the Arts (Zhonghua Yishu Daxue) in Shanghai, studying under artist Chen Baoyi (1893-1945) in the Department of Western-Style Art. After graduating in 1927 the artist continued her studies in Japan at the Academy of Culture (Bunka Gakuin) in Tokyo. While in Japan, she was also associated with artists Ikuma Arishima (1882-1974) and Kigen Nakagawa (1892-1972), who were important figures in the development of modern Western-style art in Japan.

Guan’s artistic style, characterised by bright, bold colours and thick brushstrokes, reflects the educational and creative environment in which she received her training. While many European Post-Impressionist artists were influenced by Japonisme, such artistic and cultural exchange was multi-directional. Indeed, Japanese modern artists of the 1920s and 1930s were captivated by Fauvism. Because Guan studied in Tokyo at the height of this Western creative influence, her artwork exudes the spirit of the Fauves. For example, in Portrait of Miss L (1929), Guan uses thick, loose brushstrokes and flat, playful planes of colour reminiscent of the work of Henri Matisse (1869-1954). However, the character depicted in Portrait of Miss L is a modern Shanghai woman: the distinctly Chinese identity of the sitter is denoted through the inclusion of fashionable Shanghai clothing – including the qipao with its mandarin collar – accented by black bobbed hair and brightly rouged cheeks. Here, Guan synthesises European influence, Japanese artistic training, and national identity, showcasing her mastery of modernistic techniques.

Upon her return to Shanghai in the late 1920s, Guan was received favourably by the public and critics alike, and throughout her career she held numerous highly acclaimed solo exhibitions. In keeping with Portrait of Miss L, Guan’s oeuvre continued to be dominated by portraits of young women, including Portrait of a Young Girl (Puberty) (1941) and Lady Playing Mandolin (1940s). Portrait of a Young Girl features Guan’s characteristically spontaneous brushwork but is solemn and darker in hue than Lady Playing Mandolin, which abounds with brightly coloured patterns that extend beyond the edges of the canvas.

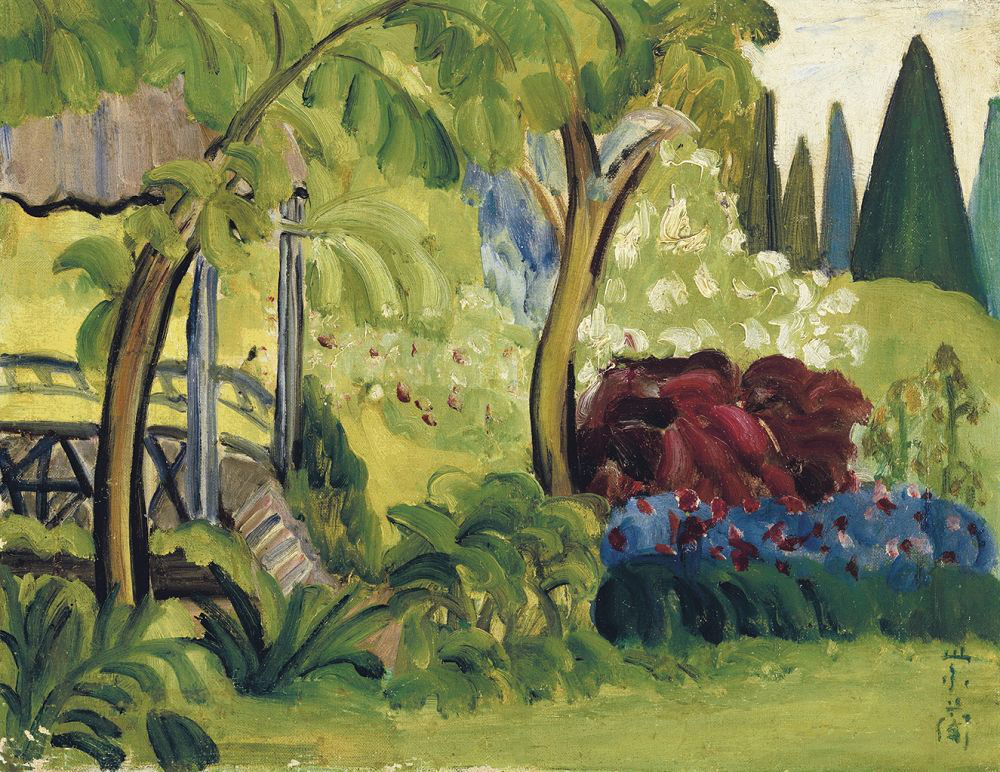

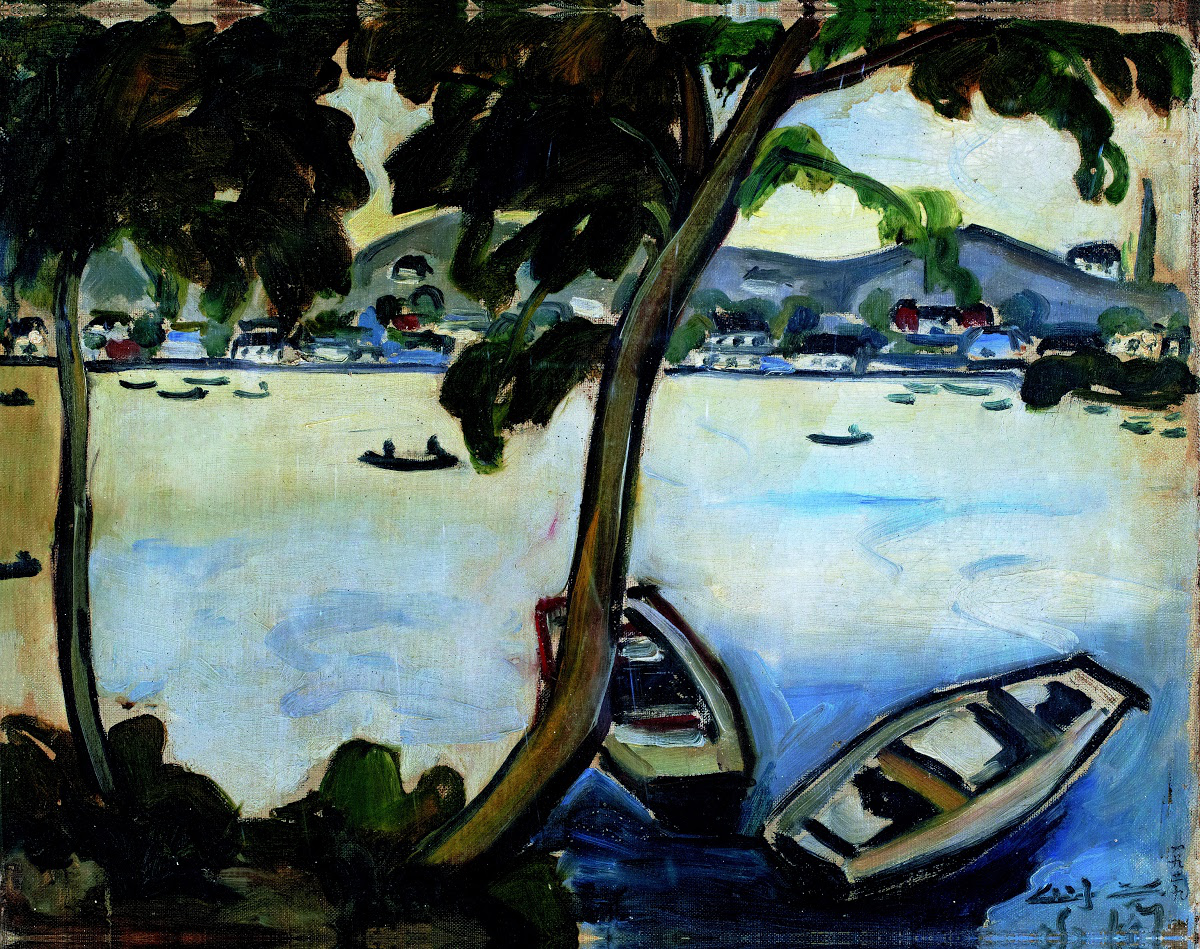

In addition to her portraits of young women, Guan painted still lifes, landscapes and flower studies. Still Life with Fish (1930s) buzzes with vibrant swaths of highly saturated pigments, and both her subject matter and use of striking purples in Chinese Wisteria (1931) is befitting of her anglicised name “Violet Kwan” (zilan means “violet,” the flower). Featured in her 1930 Shanghai solo exhibition held at the Hua’an Building in Shanghai, The Views of West Lake (1929) demonstrates her knowledge of Impressionist brushwork as well as ukiyo-e framing techniques in which a large, cropped object is typically placed in the foreground. In the years preceding the Cultural Revolution, Guan turned to realism, a shift evident in the less abstract delineation of flora in Vase of Flowers (1966).

Guan continued to exhibit her paintings while working as a fine arts instructor until ultimately ceasing her artistic production at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

A notice produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2022