Research

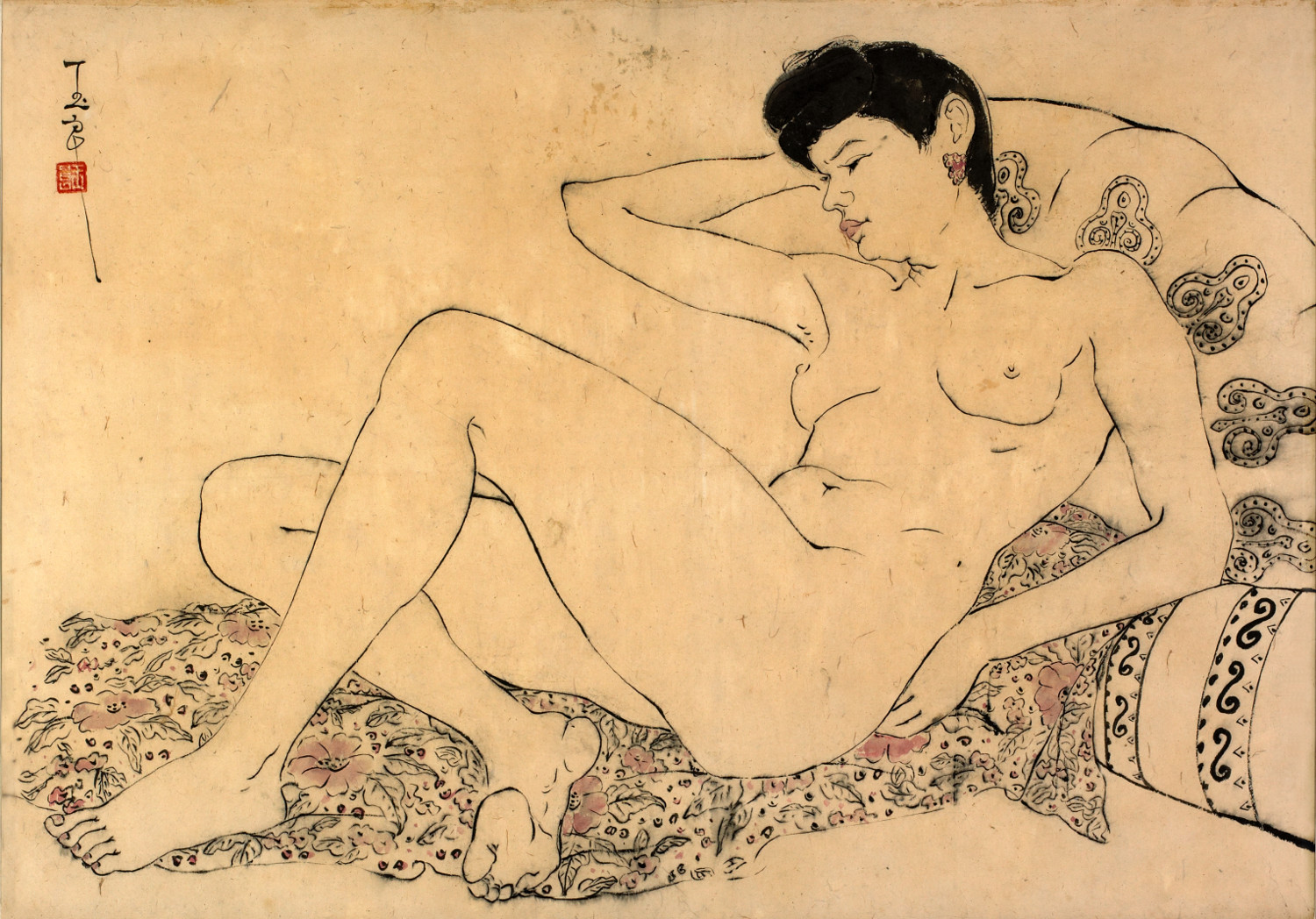

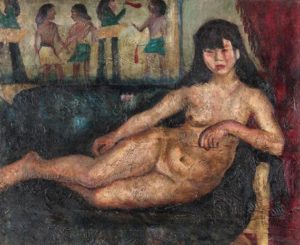

Pan Yuliang, Nu, ca. 1946, Centre national des arts plastiques, on deposit at Musée National d’Art Moderne, © Rights reserved/Cnap, © Photo: Yves Chenot

On 10 April 1929, the First National Art Exhibition opened to the public in Shanghai and manifested itself as an unprecedented art event within the Chinese art world of the Republican era. Organised at the initiative of a group of established artists who sought to demonstrate the range and accomplishments of Chinese art to a national and international audience, the show went down in history as the precedent of large-scale interdisciplinary exhibition-making in modern China. The ambitious project comprised more than two thousand works and eventually played a vital role in the canonisation of Chinese modern art, as it sparked lively debates about art and future artistic developments.

As a whole, it represented a unified modern nation and contemporary developments in the field of art.1 Especially the display of paintings of the nude – a genre that had no obvious tradition in China – was unprecedented for such a seminal art event, as nudity did not exist in public. In contrast to Western art tradition, in which the representation of the naked body has played a vital role since antiquity, the subject matter did not appear until the end of the nineteenth century “as part of the Occident’s creation of an ‘Oriental’ other,” as John Hay observes.2 Notwithstanding, the nude did enter modern Chinese art history when the modernisation processes – known as the New Culture Movement of the 1920s and 1930s – swept over the entire country and China experienced the rejection of traditional ethics and Confucian gender roles. After numerous students returned from studying abroad in Japan and Europe (mainly France), the practice of drawing from male and female models in life drawing classes was introduced,3 and Chinese artists ultimately started developing their own tradition and styles in nude painting. What is more, images of the female nude turned into a popular subject and became the signifier for the modernisation of Chinese art as a whole.4

As far as the public reception of women artists was concerned, however, they were rather disparaged as models and muses on the canvases than accepted as professional artists standing in front of them. Phyllis Teo summarises this dichotomy: “In the Chinese tradition, male artists and writers were entitled to use symbolic expressions for their aesthetic pursuit of taboo subjects like sexuality, while their female colleagues were required to stay uninvolved in such topics, in keeping with Confucian propriety.”5 This article begs to differ. I argue that as women were liberated from Confucian gender roles at the beginning of the twentieth century, female artists assumed agency over their own bodies and representations. The following paragraphs will thus expound on the inclusion of nude paintings produced by female artists that were included in the First National Art Exhibition and inside the magazine Funü Zazhi (also called The Ladies’ Journal), which was published between 1915 and 1931 and regularly reported on women artists. Moreover, it highlighted the topic of art and echoed the contemporary emphasis on aesthetic education and thus served as an essential source for fostering the discourse on women’s art in China. It documented distinctive aspects of Chinese women’s art practices in the early twentieth century, which was rather exceptional for art publications of the Republican era. Notwithstanding, the mainstream discourse on women’s art was led by male critics and organisers, and a magazine like Funü Zazhi proved to be essential for the emancipation of women’s art in China. Doris Sung points out: “The 1929 special issue of The Ladies’ Journal on the First National Art Exhibition was, therefore, a long-awaited platform for women artists to express their thoughts in writing.”6

Looking more closely at this special edition of Funü Zazhi,7 it can be said that it provided an important critical forum for the discussion and dissemination of women’s art. Not only were their works reviewed and praised in a critical manner but moreover the biographies of twenty-four female artists were published alongside their portraits and copies of their artworks8 – some of which were nude paintings, which will be discussed below – as well as a wide range of articles by renowned writers and critics. Such high-profile coverage on women’s art was rather unique among art publications of the Republican era and it thus acted as a liberating discursive platform. Women’s magazines in general became a highly anticipated platform for women to express their own thoughts, opinions, preferences and styles and in the case of Funü Zazhi, it contributed to the introduction of female artists to a wider audience and defied the mainstream discourse on women’s art that was predominantly led by male critics, artists and curators.

Wang Jingyuan, Plaster statue of a grief stricken woman, The Ladies’ Journal, 1929

Tang Yunyu, Reclining Nude on a Green Couch, ca. 1930-1949, oil on canvas, 67 x 82 cm

Again, I want to stress the argument that women artists practicing in the genre of nude painting – or practising at all – could not be taken for granted. It was a practice that requested agency and confidence. It can thus be argued that female artists working in the field of nude painting defied not only a male-dominated art world but moreover succeeded in expressing an awareness of their individual identity as well as a specific female consciousness for the first time on a public stage.9 Several artists included in the National Exhibition as well as in Funü Zazhi exemplify this argument. Wang Jingyuan, for instance, a sculptor and professor at the National Art Academy, presented a nude female sculpture titled Plaster Statue of a Grief-Stricken Woman (1929), which unabashedly expressed a woman’s pain and sorrow – a subject matter that was highly uncommon at that time. In Tang Yunyu’s Reclining Nude on a Green Couch (1930-1949),10 an unclothed woman reclines nonchalantly on a couch, consciously gazing at the viewer, without catering to the preferences of the (male) gaze. In my view, Tang Yunyu’s female figure externalises a powerful presence that is rarely encountered in artworks produced in the 1920s.

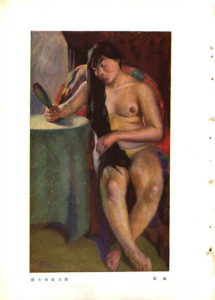

Pan Yuliang, Looking at a Reflection, The Ladies’ Journal, 1929

Pan Yuliang, The Man Lying in the Light, The Ladies’ Journal, 1929

Last but not least, Pan Yuliang, who is one of the most prolific and renowned female artists of her time. She was one of the first female students to be accepted to the Shanghai Art Academy (where she later also taught as a professor) and studied painting in France and Italy. Ultimately, Pan Yuliang developed her own painterly style and subject matter, which particularly focused on herself as a woman in a male-dominated and/or Western society and produced a collection of myriad nudes in oil, ink and watercolours. Unsurprisingly, she was represented with five works at the National Art Exhibition, two of which was Looking at a Reflection (1929), which also made it onto the first page of the colour-plate section of Funü Zazhi, and The Man Lying in the Light (1929). In the former, we see a confident woman, observing herself in a hand mirror, naked except for a few parts covered by her long black hair. One of the reviews of her work stated: “The contour is accurate; the colours, passionate… the brushstrokes, rich with an oriental flavour… the best painting featured in this exhibition.”11 What is more, Pan Yuliang portrays the woman self-confidently, conscious of her existence, directing the gaze towards herself. Similar to the Western tradition of self-portraits with mirrors – a powerful subject matter for women artists at the beginning of the twentieth century12 – the mirror does not stand as an allegory for vanity but becomes a symbol for the search for truth beneath the surface.

The high-profile coverage on women’s art practices thus manifested itself as a liberating discursive platform to express women’s newfound agency and it ultimately contributed to the establishment of future women’s art organisations and exhibitions. Between the 1920s and 1930s there existed around eighty-five painting societies,13 some of which allowed female artists to become members and even actively promoted the position of women in the art. Eventually, in 1934, the Women’s Painting and Calligraphy Society was established, which counted more than 150 members and resulted in a pivotal milestone in many women’s careers. It was the most renowned association of women artists in Chinese modern art history and fostered the emancipation of their individual practices.

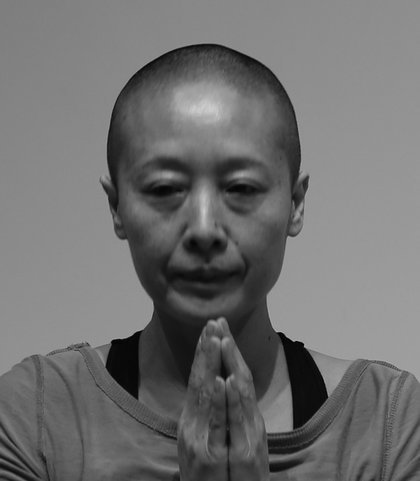

He Chengyao, Testimony, Chromogenic photographs, 2001-2002, each: 118.9 x 74.4 cm, Brooklyn Museum, © He Chengyao

Li Xinmo, Same Body, 2009, photograph, Courtesy Li Xinmo

All of these developments resulted in an unprecedented counter-discourse to the modern art canon and the female body emancipated itself from merely being an object on the canvases to becoming a multifaceted subject matter. Nudes were finally painted by women artists standing in front of the easel, a development that served as signifier of modern national discourse and art formation during the 1920s and 1930s. These modernisation processes came to an abrupt halt, however, as art and artists were bound to fulfil propagandist purposes during the Mao era (1949-1976). Art was to reflect Socialist reality and artists were to serve the people, which consequently meant the banning of all bourgeois Western art styles. Nevertheless, art recovered steadily and Chinese contemporary art developed into an internationally successful genre, after the country opened up to the outside world in the 1980s. Artists were able to express themselves freely and female artists were again starting to incorporate their own experiences, perspectives and female consciousness through art, which often incorporated the naked body as medium. In an unprecedented way, many female artists were challenging the taboo subject of nudity by staging shocking performances or by producing provocative imagery. Artists such as He Chengyao (born in 1964), Chen Lingyang (born in 1975) and Li Xinmo (born in 1976) have consequently produced some of the most radical artworks since the 1990s. These artworks remain exceptional beacons in the history of women’s art up until the twenty-first century, as in today’s climate the public presentation of the naked body is subject to inspection by the authorities and often falls prey to (self-)censorship. Notwithstanding, the history of the nude in Chinese art continues to be written.

Andrews Julia and Shen Kuiyi, The Art of Modern China, Los Angeles, University of California Press, 2012, p. 64.

2

Hay John, “The Body Invisible in Chinese Art?” in Barlow Tani E. and Zito Angela (eds.), Body, Subject & Power, Chicago, Chicago University Press, 1994, p. 43.

3

Most prominently by Liu Haisu and Li Shutong.

4

Even though censorship and the prohibition of their public representation by the authorities, as well as public controversies, ensued for decades.

5

Teo Phyllis, “Modernism and Orientalism: The Ambiguous Nudes of Chinese Artist Pan Yuliang”, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 12, 2, December 2010, p. 71.

6

Sung Doris, “Redefining Female Talent: The Women’s Eastern Times, The Ladies’ Journal, and the Development of ‘Women’s Art’ in China, 1910s-1930s”, in Michel Hockx et. al. (eds.), Women and the Periodical Press in China’s Long Twentieth Century: A Space of Their Own?, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2018, p. 137.

7

Funü Zazhi, 15. 7, July 1929. This issue as well as many others are partly online https://kjc-sv034.kjc.uni-heidelberg.de/frauenzeitschriften/public/magazine/issue_detail.php?magazin_id=4&year=192 9&issue_id=441&issue_number=007

8

Pan Yuliang, Tang Yunyu, Wu Qingxia, Cai Weilian, Feng Wenfeng, Yang Xuejiu, Chen Xiaocui, Jin Qijing, Jin Naixian, Hong Jing Yi, Wu Wanlan, Tao Cuiying, Liang Tianzhen, Cai Shaomin, Li You, Zhou Lihua, Yang Manhua, Wu Peizhang, Wang Yinru, Fang Junbi, Fang Jun, Fang Yu, Weng Yuanchun and Wang Zuyun.

9

Drawing from my own research conducted for the PhD thesis of author that focuses on reconstructing a trajectory of all-female group exhibitions in China.

10

There is no copy of this work in Funü Zazhi but the records show that one of her nudes was included in the National Exhibition.

11

Hong Xu, “Early 20th-Century Women Painters in Shanghai”, in Birnie Danzker Jo-Anne et al. (eds.), Shanghai Modern, 1919-1945, Ostfildern-Ruit, Hatje Cantz, 2004, p. 210.

12

See further: Meskimmon Marsha, The Art of Reflection. Women Artists’ Self-Portraiture in the Twentieth Century, New York, Columbia University Press, 1996.

13

Such as the Storm Society, the Bee Society, the Lake Society and the Chinese Painting Society.

Julia Hartmann is an art historian and independent curator based in Vienna (www.juliahartmann.at). She previously worked as Assistant Curator at the Secession and the Belvedere 21 and is currently a PhD candidate at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna with a research focus on an all-female exhibition history and “women’s art” from China. She is the co-founder of SALOON Vienna, an international network for women in the arts and curates exhibitions that oscillate between feminism, digitisation and activism.

Julia Hartmann, "Nudes in 1920s China: Emancipation and Agency in the Works of Female Artists." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/le-nu-dans-la-chine-des-annees-1920-emancipation-et-autodetermination-dans-les-oeuvres-dartistes-femmes/. Accessed 26 April 2025