Helen Frankenthaler

John Elderfield, Frankenthaler, New York, Harry N. Abrams, 1989

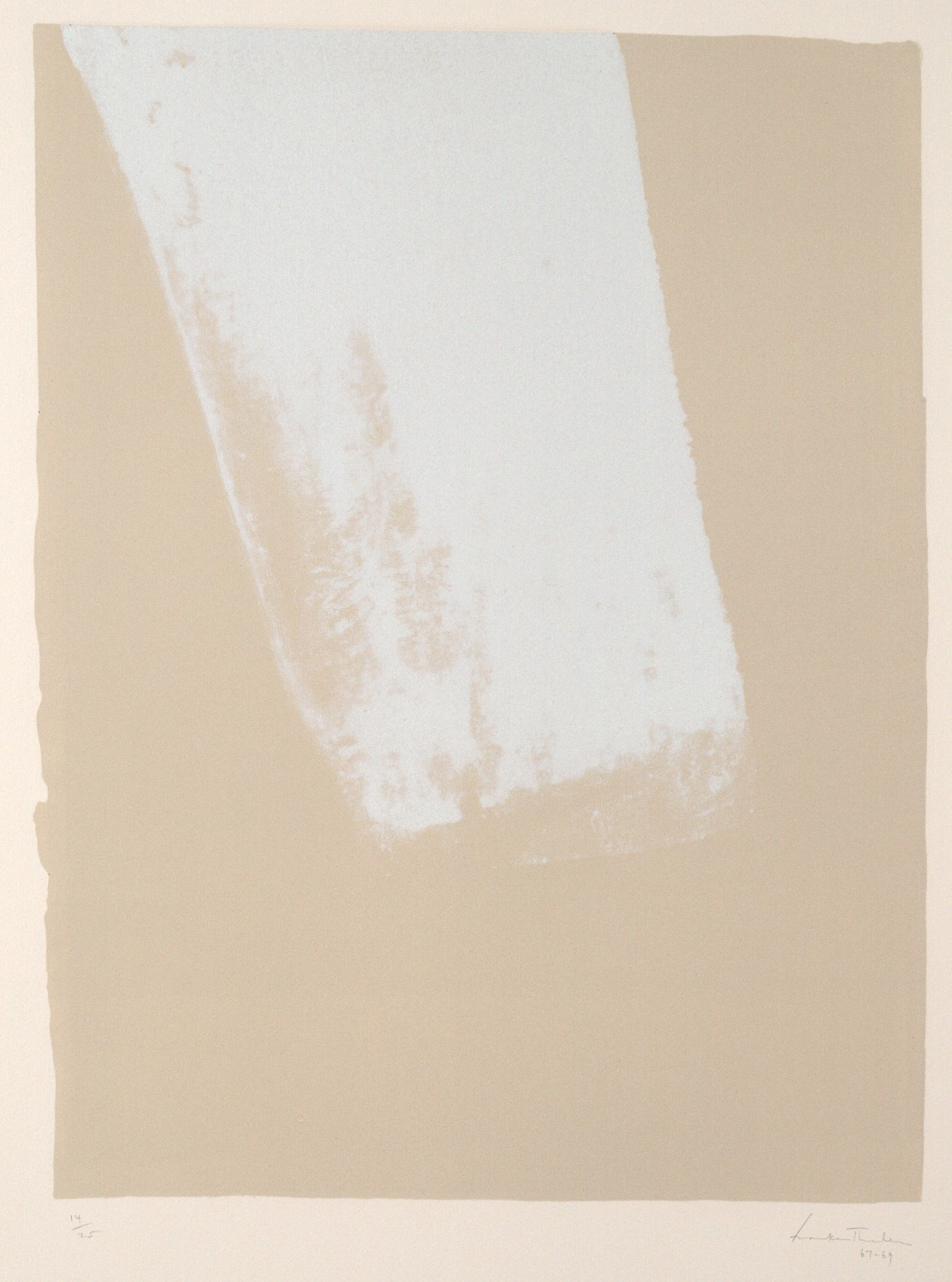

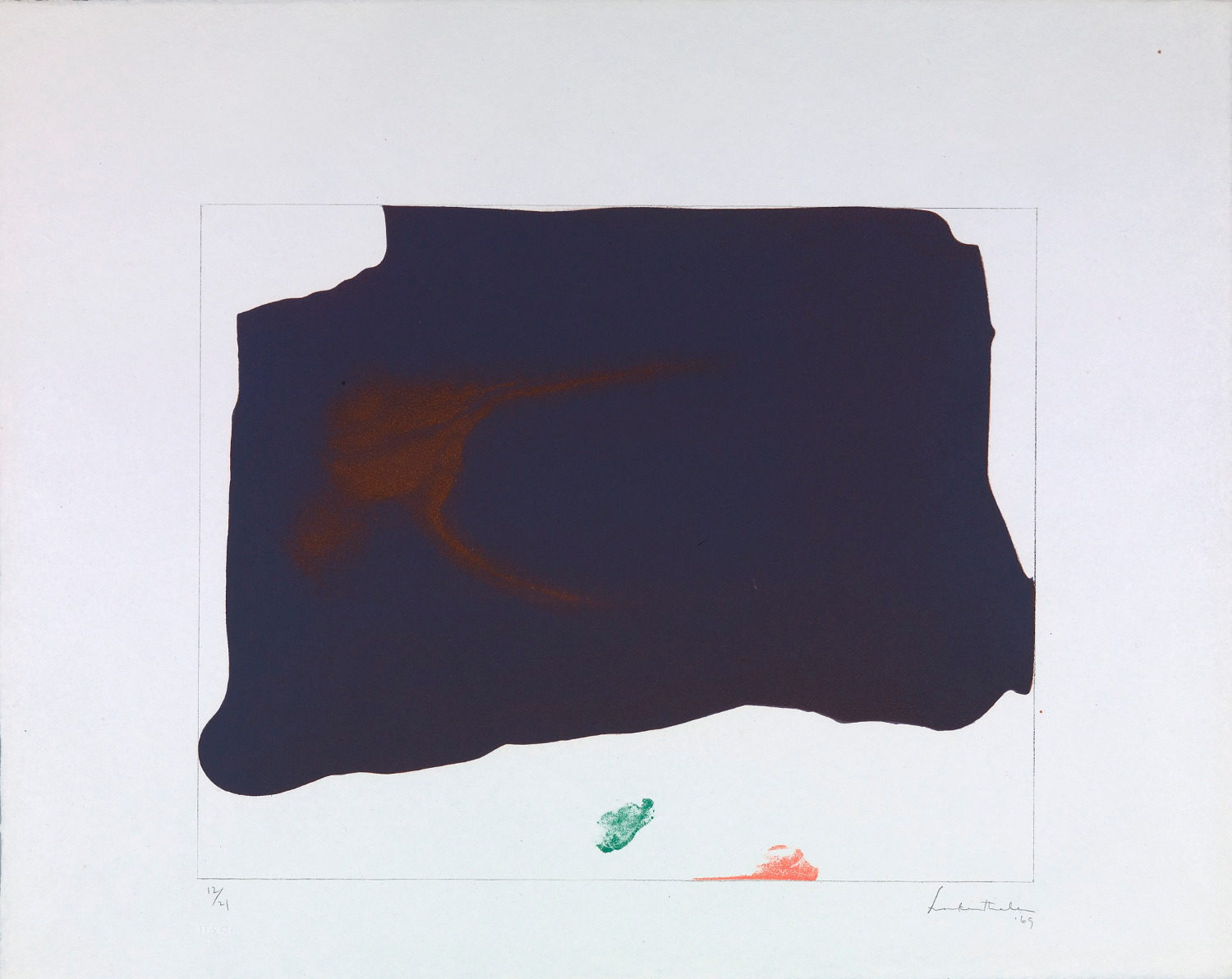

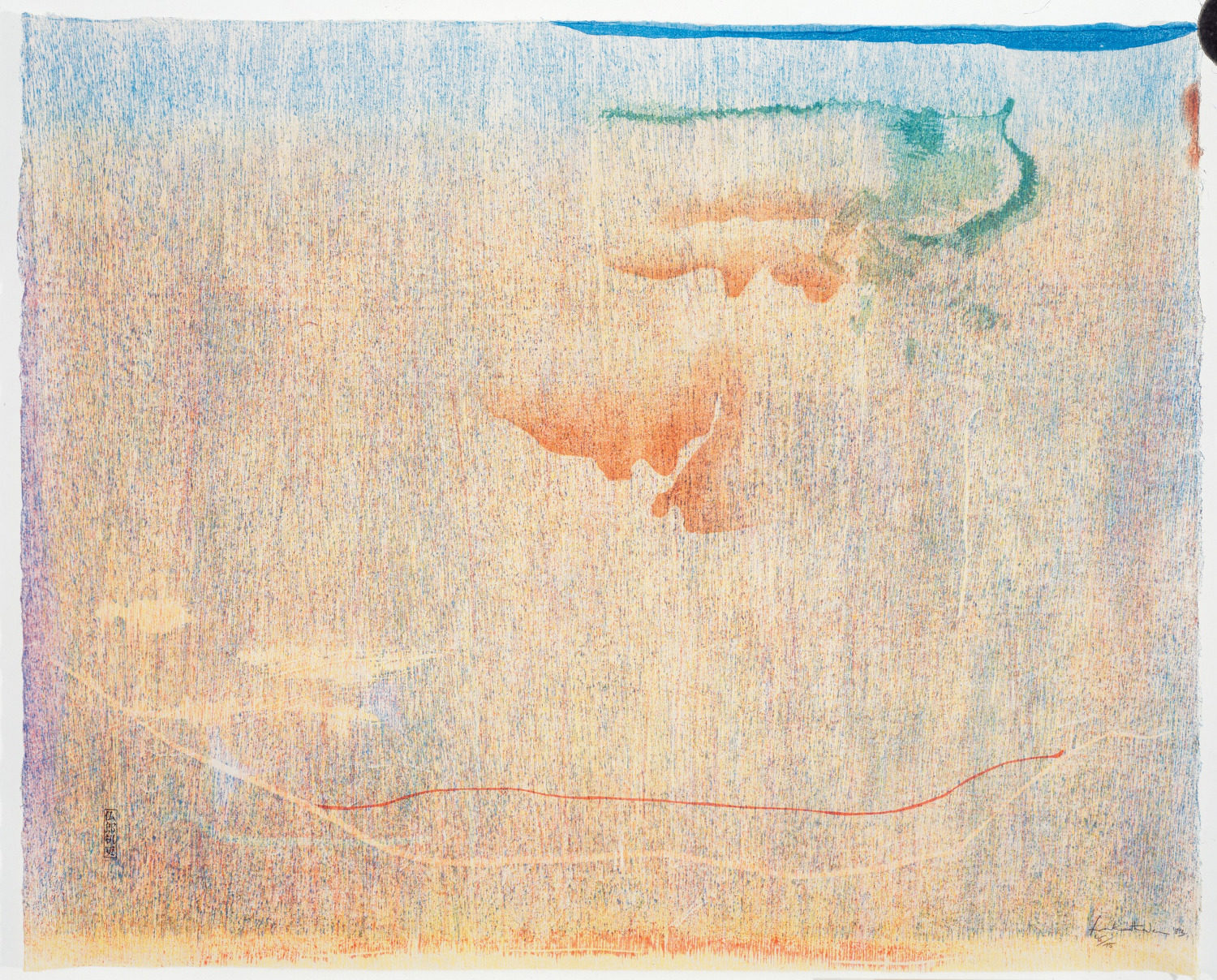

→Pegram Harrison & Suzanne Boorsch, Frankenthaler: A Catalogue Raisonné, Prints, 1961-1994, New York, Harry N. Abrams, 1996

→Clearwater Bonnie (ed.), Frankenthaler, Paintings on Paper 1949-2002, exh. cat., Museum of Contemporary Art, Miami (2003), Miami, Museum of Contemporary Art, 2003

Helen Frankenthaler, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1969

→

Helen Frankenthaler: a Painting Retrospective, The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth ; Museum of Modern Art, New York ; Los Angeles County Museum of Art ; Detroit Institute of Arts, 1989-1990

→Helen Frankenthaler Prints: The Romance of a New Medium, The Art Institute of Chicago, 20 April – 3 September 2018

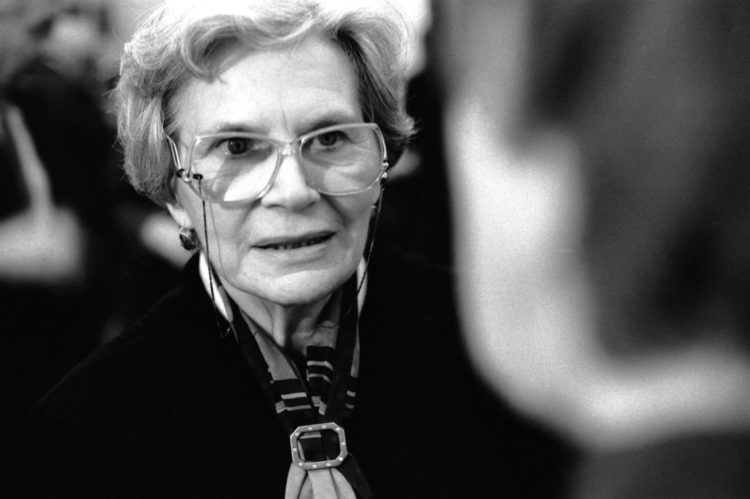

Peintre américaine.

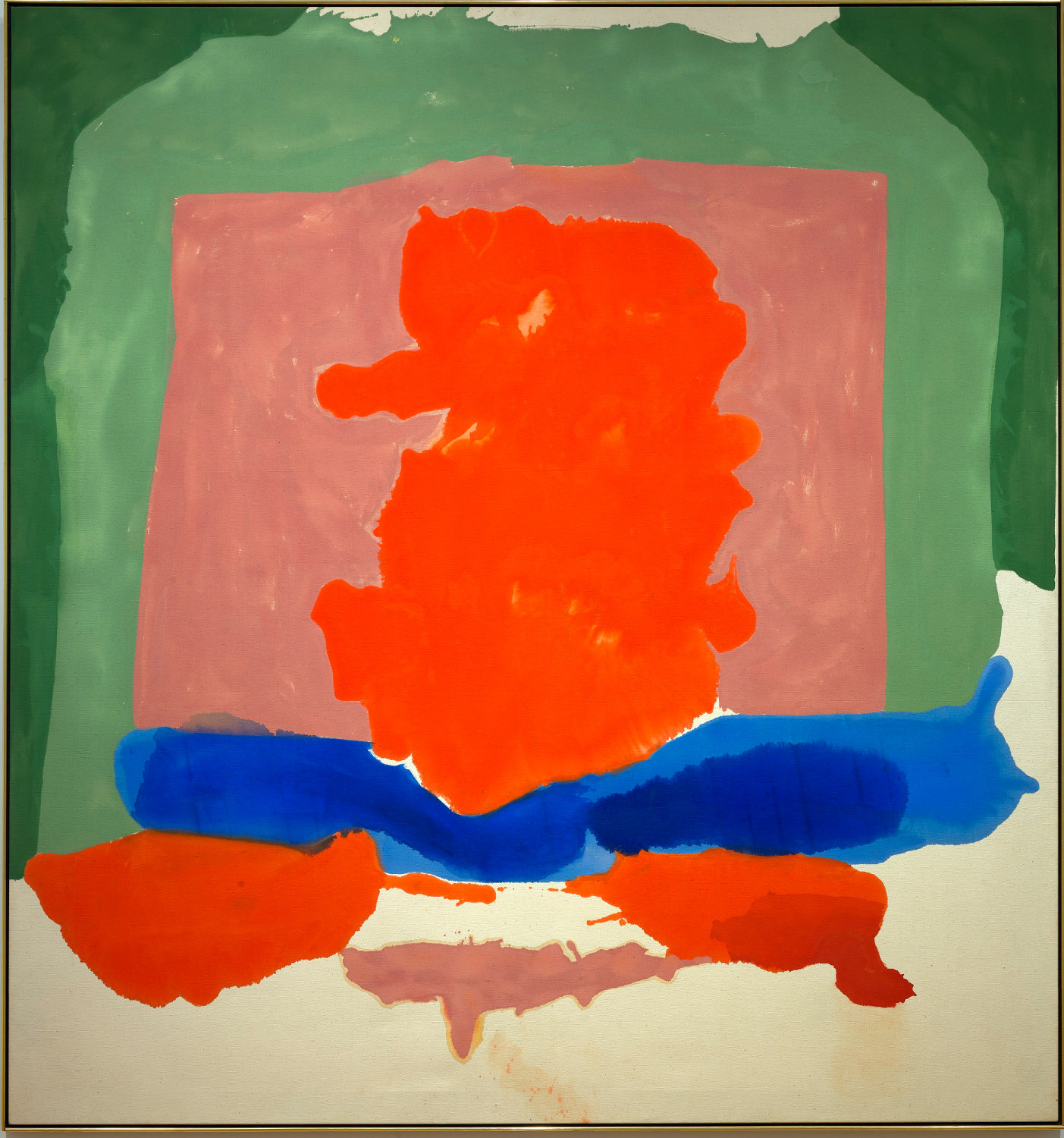

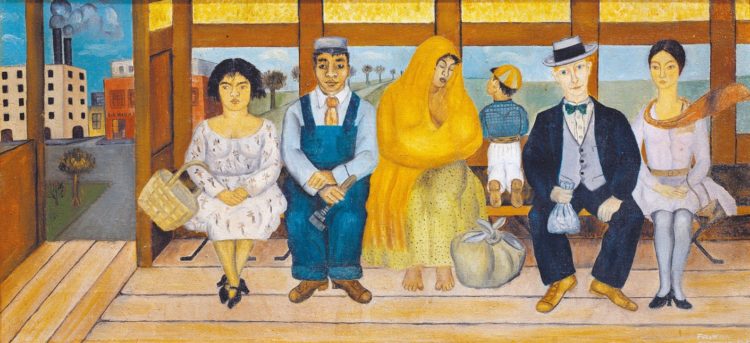

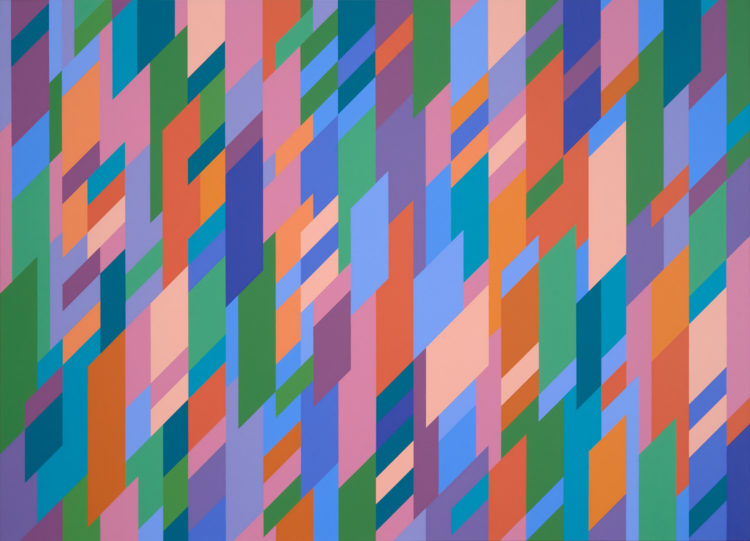

A major artist of the abstract expressionist movement, Helen Frankenthaler marked the transition to Colour Field painting. The daughter of State Supreme Court judge Alfred Frankenthaler and Martha Lowenstein, she graduated from the Dalton School in 1945 and studied at Bennington College in Vermont. At first inspired by Cubism, her work later turned toward landscape, reflecting the influence of European painting. In 1950, she met and became the partner of the critic Clement Greenberg, and befriended the artists David Smith, Lee Krasner, Jackson Pollock, Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Franz Kline, Adolph Gottlieb, and Barnett Newman. The presentation of her painting Mountains and See at her second solo exhibition at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in 1953 was a major highlight of her career. In the 1950s, she travelled to Europe, where she discovered Titian, Velázquez, Matisse, and Monet. She married the artist Robert Motherwell (1915-1991) in 1958, whom she divorced in 1971. In 1959, her work was featured in the collective publication School of New York: Some Young Artists, edited by Bernard H. Friedman, and her work shown at documenta 2 Kassel, at the fifth São Paulo Biennale, and at the Paris Biennale, which featured her painting Jacob’s Ladder. Her first retrospective took place at the Jewish Museum of New York in 1960. In 1961, she took part in the American Abstract Expressionists and Imagists exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum of New York. With Mountains and Sea (1952), the artist developed the “stained colour” technique, in which paint is used as dye to directly impregnate the canvas. This technique, from which Colour Field painting originated, would influence painters such as Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, and Jules Olitski. This large abstract painting uses a fairly pale range of colours – orange red, green, and blue – evoking the landscapes mentioned in the title. Another element of this painting is noteworthy: the artist could have erased the preliminary charcoal outlines of the shapes and colours in the landscape once the painting was completed, but chose to keep them. The interaction among the lines and the paint, the use of colour, and the blank, unpainted portion of canvas prompted the following words from Clement Greenberg: “Is it finished? Is it a complete picture?” – a famous quote for an equally famous painting.

In her 1958 piece Las Mayas, Frankenthaler paid tribute to Goya, taking inspiration from his Majas on a Balcony, whose composition she reversed vertically: several elements of the painting remain recognisable, such as the balcony’s guardrail, which she reworked as green drippings and swiftly drawn lines, and the blank space at the centre of the canvas. Nude, painted the same year in a similar format, is an abstract take on the nude: nothing but a blue rectangle – the lines of which could figure a head – suggests the presence of a body. The artist worked on this painting both vertically and on the floor. Even more so than in Las Mayas, the blank of the canvas becomes a major element that brings luminosity to the painting. The dots accidentally spattered by the brush and the quickly traced lines are the dynamic elements in both paintings. During the 1960s, Frankenthaler’s relationship to form and colour changed. The construction of Tangerine (1964), described as “the most abstract” work of the same series, relies entirely on colour: a shape painted in four different shades of orange, which blend together in the topmost part and remain more contrasted at the bottom, where they are framed with green, leave room for a blank rectangle underlined by a dark stripe at the bottom of the canvas. The combination of still life (the “tangerine”) and coloured shapes is a perfect example of abstraction with a descriptive quality. In the 1970s, her surfaces became denser and more worked, as is the case in Salome (1978), which uses much more contrasted colour overlaps on surfaces to express movement. Her paintings of the 1980s reverted to a Cubist framework combined with a more spontaneous workmanship, particularly in her use of whites. Throughout her career, H. Frankenthaler’s work was that of a great painter, both thorough and delicate.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2018

A Conversation on Helen Frankenthaler

A Conversation on Helen Frankenthaler