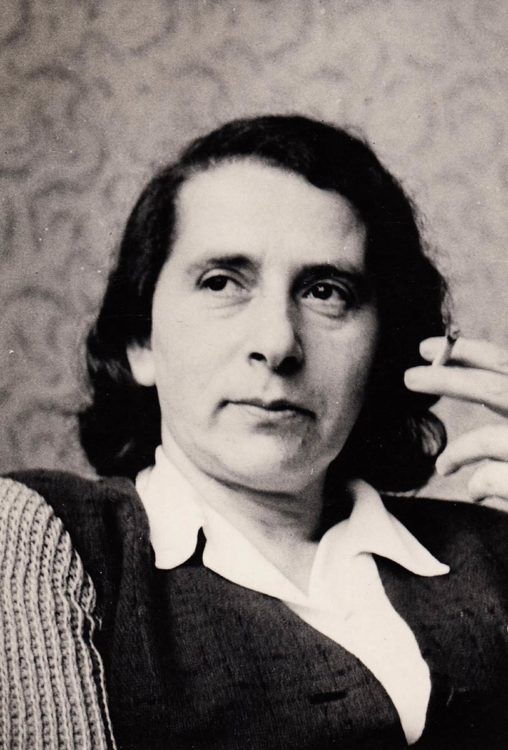

Helen Levitt

Levitt Helen, Gopnik Alan, Here and There, New York, PowerHouse Books, 2003

→Levitt Helen, Szarkowski John, Slide Show: The Color Photographs of Helen Levitt, New York, PowerHouse Books, 2005

→Phillips Sandra S., Hambourg Maria Morris, 1991–Helen Levitt, San Francisco, San Francisco Museum

of Modern Art

Chevrier Jean-François, Ribalta Jorge, Trachtenberg Alan (ed.), Helen Levitt, un lyrisme urbain, Cherbourg-Octeville, Le Point du jour, 2010

Helen Levitt, Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris, 12 September–23 December 2007

→Projects: Helen Levitt in Color, MoMA, New York, 16 September–20 October 1974

American photographer.

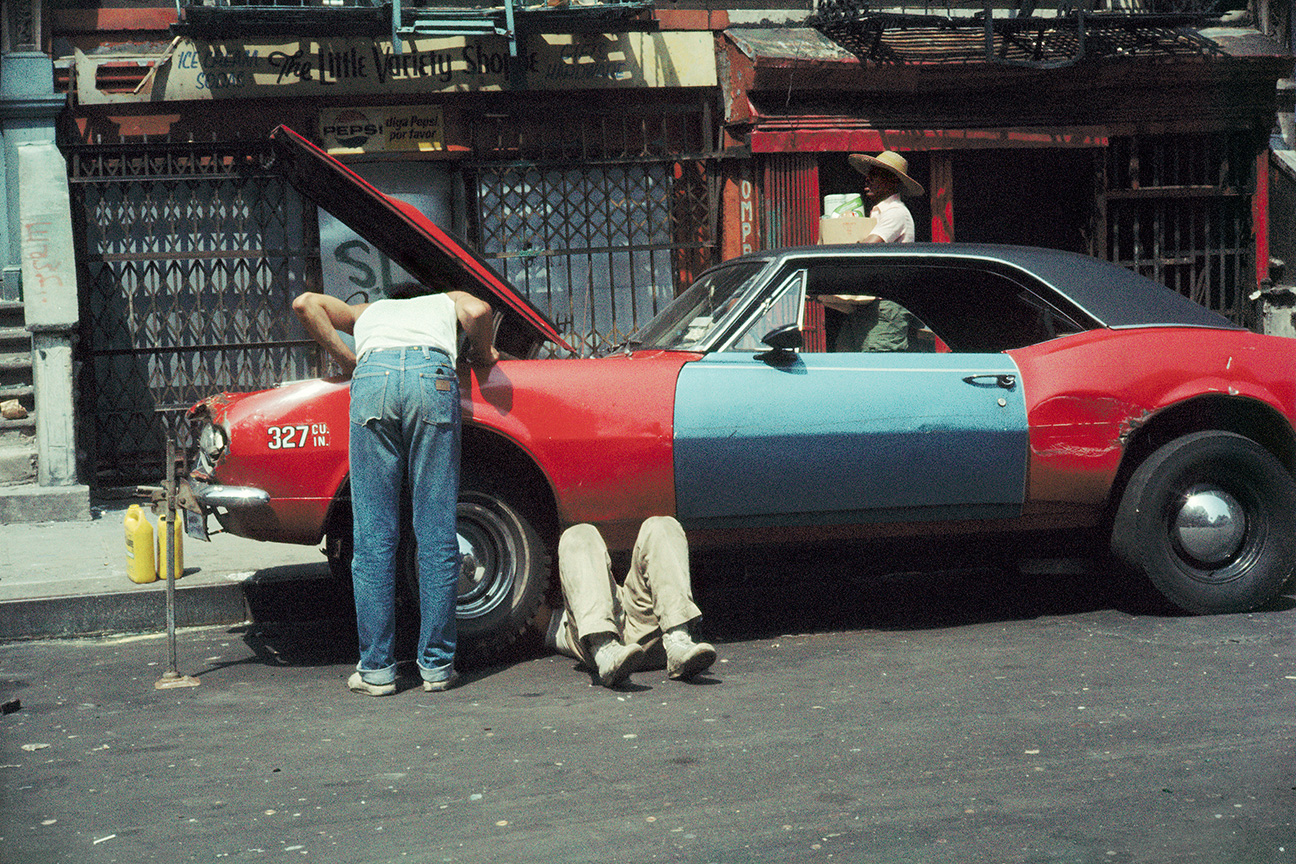

Helen Levitt, who is inseparably linked to New York, took large numbers of photographs of the day-to-day life and the children of Harlem, Brooklyn, and the Lower Eastside. In the early 1930s, she worked with a portrait photographer in the Bronx, but it was her encounters with Henri Cartier-Bresson and Walker Evans, for whom she was an assistant in 1938-1939, which were decisive in her choice of career. She purchased her first Leica in 1936 to photograph the chalk drawings of kids in the street whom she taught art (In the Street: Chalk Drawings and Messages, New York City, 1938-1948). Despite her use of the Leica, symbol of the boom in photographing reality between the wars, she was neither a photojournalist, nor a documentary photographer. Like Cartier-Bresson’s photographs, her images belonged to an “Art of the poetic accident”, which was the title of the retrospective show devoted to her work by the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation in 2007. They try to capture the energy, poetry and bustle of the New York melting pot. Because she photographed Harlem a great deal, she is sometimes seen as a social photographer, but, as the famous museum curator John Szarkowski explains, it was above all because life in modest neighborhoods is “socially rich and visually interesting” that she worked in them.

In this way, New York is at once a character and a décor, where children play and teenagers pose. These unposed images, taken with a 35mm camera, call to mind the French film movement of poetic realism. Shoes left on the pavement, children hiding under cars (New York, 1980), parents disappearing in landaus: the street becomes a merry, popular theatre. Behind the fantasy, however, a sort of anxiety shows through: the masks and disguises are sometimes distressing, and poverty is clearly visible. But many images also play on the contrast between the morose atmosphere of interiors and the exuberance of the characters photographed.

In 1943, the photographer earned an early relative recognition, thanks to the photographer Edward Steichen who enabled her to hold her first solo exhibition at the prestigious Museum of Modern Art (MoMA): Children: Photographs of Helen Levitt. In collaboration with the writer James Agee and filmmaker Janice Loeb, she made two films, The Quiet One (1949) and In the Street (1952), regarded as forerunners of independent American film. In 1959-1960, she received a grant from the Guggenheim Foundation to study colour photography. At that time she was seen as a pioneer: the turning point was risky, but successful. Despite the theft of a large part of her colour photographs in 1970, she continued with her experiments and presented her images in Slide Show, a screening organized at the MoMA in 1974. Various retrospective shows then emphasized the coherence of her career (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1991; Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation, Paris, 2007).

Her colour photographs, which have been a major source of inspiration for many photographers, nevertheless remain less well known among the general public than her black and white works, brought together in A Way of Seeing (1965). These snippets of everyday life are typical of urban American photography in the 1960s and 1970s, which owes the artist a considerable debt. Levitt did not belong to any school: close to photo-reportage and documentary photography, but without subscribing to either, her work was, according to Agee, “a moderate but irrefutable manifesto of a certain way of seeing things, gentle and thoroughly devoid of pretension”. In France, the first exhibition of her photos was not held until 1998. Her work, which was late to be recognized, is compared to humanist photography, but her artistic approach, her work on the interplay of glances, arrested movements and the evocative power of the off-screen, all belong more to the American documentary tradition. Stripped of any political message and didactic intent, her art was above all an art of observation.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017