Hélène Bertaux

Jacques, Sophie, La statuaire Hélène Bertaux (1825-1909) et la tradition académique. Analyse de trois nus, Quebec, Laval University, 2015

→Rivière, Anne (ed.), Sculpture’Elles. Les sculpteurs femmes du XVIIIe siècle à nos jours, Paris, Somogy, 2011

→Lepage, Édouard, Une page de l’Histoire de l’art au XIXe siècle. Une conquête féministe : Mme Léon Bertaux, Paris, Imprimerie française J. Dangon, 1911

Sculpture’Elles. Les sculpteurs femmes du XVIIIe siècle à nos jours, Paris, Musée des années 30, May 12 – October 2, 2011.

→Exposition internationale de Chicago, Women’s Building, 1893

French sculptor.

Sculptor Hélène Bertaux is remarkable for the central role she played in the education and recognition of women artists. Born Hélène Pilate to a family of artisans, she grew up in an environment that encouraged artistic expression. As a teenager she trained in the studio of her stepfather Pierre Hébert (1804-1869), where she modelled ornamental pieces for clocks. She received regular commissions for small decorative bronzes thanks to her patron, Victor Paillard, whom she met in 1855. Eager to become a professional sculptor, she completed her training with Augustin Dumont (1801-1884) in the academic tradition.

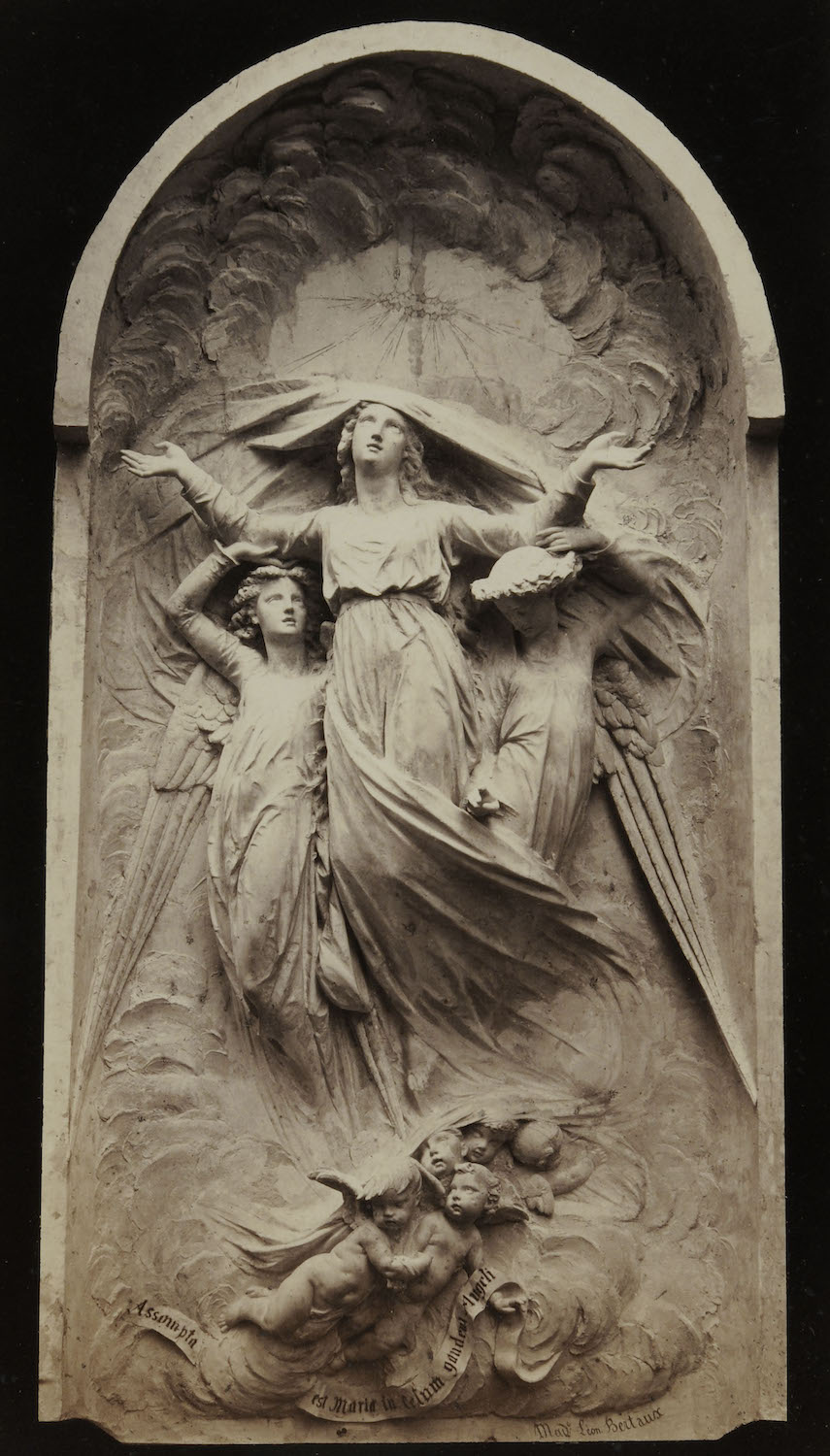

The 1860s were a turning point in her career. Her keenness to assert herself as equal to men led her to present Jeune Gaulois prisonnier des Romains (Young Gallic prisoner of the Romans, 1864) at the Salon. The piece is the first known heroic male nude made by a woman sculptor. The neo-Canovian aesthetic and synoptic elegance of the hunched figure in her work positioned her as part of the French sculpture revival movement. The piece earned her a medal and success, and she rose to fame as “Mme Léon Bertaux”, the name of her partner and later husband Léon Bertaux (1827-1915) – a way of showing her change in status and claiming a form of respectability. The support of the imperial couple enabled her to become one of the few women to make a name for herself in the field of monumental sculpture: in 1864 she created the Fontaine Herbet for the place Longueville in Amiens and she received several prestigious commissions throughout her career for religious and public buildings (the new Louvre and the Hôtel de Ville in Paris).

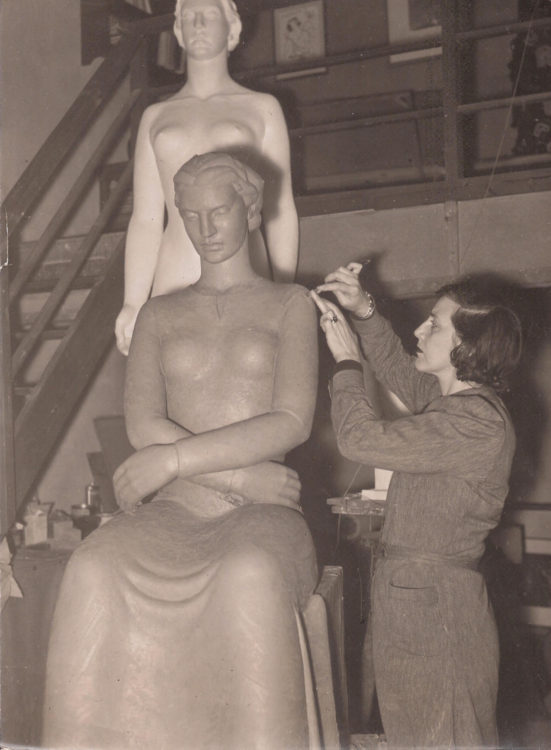

The early 1870s marked the start of a new creative period for H. Bertaux with a noticeable change in her aesthetic. With Jeune fille au bain (Young woman bathing, 1873), which earned her a medal at the 1873 Salon, she attempted to harmonise her taste for ancient art and modern subjects by drawing inspiration from Victor Hugo’s Orientalia. This pivotal period coincided with the start of her advocacy for the professionalisation of women sculptors. That same year she opened a sculpture studio at 233 bis rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, followed by another in 1879 in a mansion designed by Alfred Touret on rue de Villiers, where she opened a sculpture school for women. A number of her students went on to earn prizes at the Salon, including Clémence-Jeanne Eymard de Lanchâtres (1854-1894) and Jenny Weyl (1851-1933).

In 1881 the creation of the Union des Femmes Peintres et Sculpteurs (Union of women painters and sculptors, UFPS), for which she served as chairwoman from 1881 to 1894, signified a new step in her fight for gender equality in academic education. The Union’s aim was to organise annual exhibitions of women artists, supporting H. Bertaux’s demands to open up fine arts schools to women and allow them to enter the Prix de Rome. Meanwhile, she became the first female member of the Salon’s jury and received a gold medal at the 1889 World’s Fair for her Psyché sous l’emprise du mystère (Psyche under the influence of mystery, 1889). However, despite her many accolades, the Institut de France rejected her application twice, in 1890 and 1892. As a result of her tireless efforts with the UFPS, the École des Beaux-Arts and Villa Medici finally decided to accept women in 1897 and 1903 respectively. While H. Bertaux was later relegated to the margins of art history, feminist studies have rekindled a growing interest in her extraordinary life.

Publication made in partnership with musée d’Orsay.

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2021

![<i>La Houle</i> [The Swell]: First Research on the Place of Women Artists in the Collections of the Centre National des Arts Plastiques - AWARE](https://awarewomenartists.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/barbara-kruger_who-do-you-think-you-are_1997_aware_women-artists_artistes-femmes-750x532.jpg)