Research

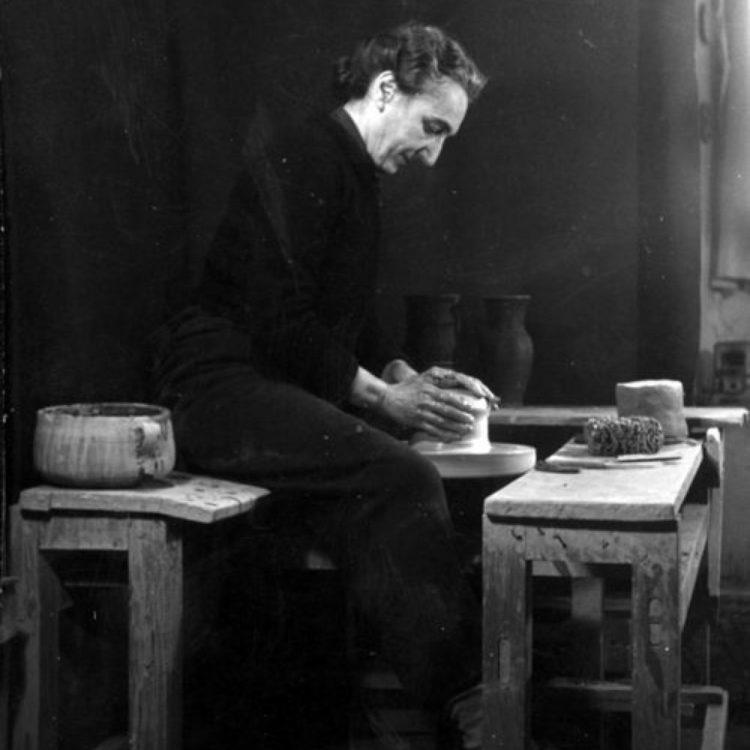

María Carmen Portela working on Anunciación [Annunciation], plaster, unknown localisation, María Carmen Portela papers, private collection

The life of sculptor and engraver María Carmen Portela (1896-1984) offers a remarkable example of the complex roles women artists have played in the Latin American art scene. M. C. Portela created iconic images, devoted herself to sculpture (often considered a masculine form of expression) for many years, contributed to the development of engraving as a medium, helped to maintain art associations, won prestigious prizes, and championed the cause of women artists. However, her long career has been obscured and remains largely unknown.

Several factors have contributed to her obliteration from art-historical narratives, besides her gender. First of all, her extended engagement with engraving, often regarded as a lesser and somewhat feminized medium, was central to her exclusion from art-history books. In addition, her focus, although non-exclusive, on women and children, not considered to be political themes per se, caused her to be associated with subjects traditionally considered those of women artists. Lastly, her frequent travels around the world and her nationalization as a citizen of Uruguay in 1964 left her outside national art histories, for it must be noted that in Latin America, as elsewhere, art histories have been written as local and nationalistic accounts.

This research article aims to explore the career of this Argentine-born Uruguayan artist, which spans more than five decades of work, social commitment and the redefinition of women’s roles. The recent rediscovery of M. C. Portela’s personal papers has allowed me to undertake an extensive analysis based upon these never before seen archival sources as well as new works.1 I will examine her aesthetic choices, her critical reception, and her impact on several Latin American art scenes.

M. C. Portela’s life could easily have followed a traditional path, confined by social mores and the economic position of her family in Buenos Aires. The artist was born into a well-to-do family and married for the first time when still a teenager, to Gustavo Caraballo. A few years later, the couple had three children and the young mother seemed to adjust to this lifestyle. However, her life would soon take a political, emotional and artistic turn, following the divorce from her husband.

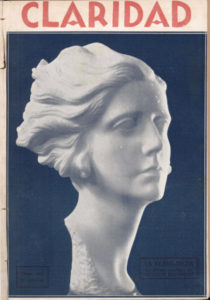

Cover of the magazine Claridad (September 25, 1927), with a reproduction of the work by Agustín Riganelli, La llamarada [The Flash], c. 1927, marble, 52 x 25 x 26 cm, Museo Sívori, Buenos Aires

The artist began her formal artistic training around 1929 with noted sculptor Agustín Riganelli (1890-1949), a close friend of the artist. M. C. Portela, who had thus far been a self-taught artist, was taking a decisive step towards professionalization. A material testimony of her relationship is the remarkable portrait of M. C. Portela, La llamarada [The Flash, c. 1927], a marble version of which is now housed in the Museo Sívori in Buenos Aires. Riganelli’s work was not exhibited as a portrait, but as a generic image of a new type of woman, closely associated with the anarchist ideas Riganelli supported alongside the artistic circle of Los Artistas del Pueblo (The People’s Artists).2

M. C. Portela’s links with socialist and anarchist circles deepened when she began a relationship with Rodolfo Aráoz Alfaro, a lawyer linked to the left-wing movement in Argentina. Leaving her past and family ties behind, M. C. Portela found a renewed sense of freedom and personal achievement. The 1930s was a decade of intense artistic activity for her. It was also a period of political unrest, profoundly shaken by the 1930 coup d’état, whose leaders were permeated by fascist ideas. The conservative group in power had been increasingly uncomfortable with the more autonomous lifestyle of many women in Argentina, but women did not simply return to their homes in the 1930s: many women played key roles in political struggle and in the art scene.3

María Carmen Portela, Amparo, unknown localisation, José León Pagano Papers, Museo de Arte Moderno, Buenos Aires

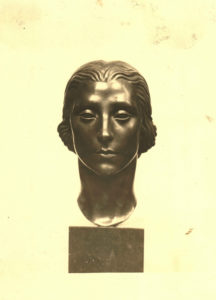

María Carmen Portela, Cabeza de mujer [Head of a Woman], bronze, unknown localisation, María Carmen Portela papers, private collection

In 1930 M. C. Portela presented a group of three sculptures at the Salón Nacional, the official salon and arguably the most established art exhibition in Buenos Aires. Amparo, a synthetic portrait of her close friend Amparo Mom, a leading figure in the anarchist and socialist circles of the 1930s, was among the works presented, for which she received an honorable mention.

In 1932 M. C. Portela presented her classicist Cabeza de mujer [Head of a Woman] at the Salón Femenino and received a prize. This was her first involvement with all-female art associations, from then on a constant in her career. The next year proved another turning point in M. C. Portela’s career. She exhibited two works at the Salón Nacional: a portrait of her father and a stunning female torso, for which she received a prize from the city hall. The art critic of the Buenos Aires’ newspaper Crítica praised the work for its audacity and sincerity.4 In 1935 another key event in M. C. Portela’s career and in the visibility of women sculptors in the Salón took place: her monumental Figura para un estanque [Figure for a Pond, 1935] received the Second National Sculpture Prize. The three major prizes of the salon had almost always been in the hands of men and M. C. Portela reached the Second Prize, while Hilda Ainscough, who first broke the glass ceiling of the sculpture, had received the Third Prize in 1931.

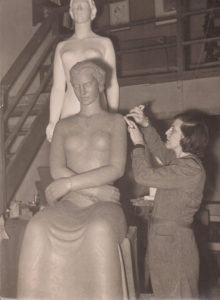

María Carmen Portela working on her Anunciación [Annunciation], plaster, unknown localisation, María Carmen Portela papers, private collection

María Carmen Portela, Figura de una atleta [Figure of an Athlete], 1940, plaster, 185 x 50 cm, Museo de Artes Plásticas Eduardo Sívori, Buenos Aires

The decade closed with two major works: Anunciación [Annunciation] and Figura de una atleta [Figure of an Athlete]. In 1938 she finished her Anunciación, a radically secular interpretation of a religious theme. The work was exhibited in the Salón Nacional and the Salón Femenino, where she received the first prize. Two years later she presented Figura de una atleta, a portrait of the remarkable athlete Olga Tassi, a pioneer in Argentine athletics. M. C. Portela was contributing to the creation of an original iconography for modern women in the Argentine art scene . The androgynous image shocked and fascinated art critics.

Although M. C. Portela never gave up sculpture, it was her preferred medium between 1930 and 1940. In the works from this period she addressed and exalted modern femininity. M. C. Portela’s first sculptural themes include female intelligence, beauty and public presence, in monumental and classicist figures. Her style is very different from Riganelli’s, as M. C. Portela sought inspiration from diverse sources, including the formal languages of Greek art and the Italian Renaissance, to create solid and intense female figures, with deep interior lives.

During these years of remarkable public exhibitions of her works, M. C. Portela embarked on a new dimension of studying art: she started to practice engraving, under the supervision of Alfredo Guido (1892-1967). Despite having experimented with several techniques, the artist preferred drypoint etching as her main form of expression during these years on. She developed a vast practice as an engraver and an illustrator of books, notably for the Sociedad Argentina de Bibliófilos (Argentine Society of Bibliophiles). Exhibited in various spaces, her graphic work won great recognition and was incorporated into the collections of several Argentine museums. In contrast with her massive sculptures, her engravings exhibit a different set of formal characteristics; subtle lines and melancholic atmospheres dominate.

María Carmen Portela, María Shistka, 1932-1933, drypoint, 15 x 24 cm, Museo Provincial de Bellas Artes Rosa Galisteo de Rodríguez, Santa Fe

The subtlety of her lines can be clearly perceived in works such as María Shistka (1932-1933). The synthetic and refined image appeared in the pages of the famous left-wing magazine Contra, praised by celebrated writer and journalist Raúl González Tuñón for its purity and quiet strength.5 The inner life of the subject, a young woman M. C. Portela portrayed several times, is rendered with an economy of means.

The 1940s saw M. C. Portela opening new professional and personal paths. Her relationship with Jesualdo Sosa, a famous Uruguayan educator, led her to deepen her ties with Uruguay, a country that welcomed M. C. Portela with open arms. In 1943 she had a major exhibition at the Amigos del Arte gallery in Montevideo. In 1965 for her work Pino entre abedules [Pine among Birches], a poetic representation of untrammeled nature, she won the National Grand Prize for Engraving at the Uruguayan salon. Her career in Uruguay was long and successful.

María Carmen Portela, Sketch for Fidel Castro’s portrait, 1962, graphite on paper, 16.4 x 27.5 cm, private collection

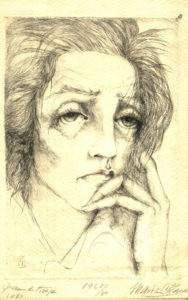

María Carmen Portela, Self-Portrait, 1965/1980, drypoint, private collection

From the 1960s her political commitment, present since her beginnings in the world of art, intensified. The artist traveled and exhibited in countries such as the German Democratic Republic, Romania and China. Between 1961 and 1962 she lived in Cuba with Jesualdo Sosa, who took part in the massive literacy campaign after the Cuban Revolution. She portrayed Cuban leader Fidel Castro several times, in sculptures and medals. In a recently rediscovered sketch of Castro, his profile merges poetically with the contours of Latin America.

M. C. Portela was an artist of her time, involved in the most progressive intellectual circles. As an active participant in these spaces, she was portrayed by artists such as Léonard Tsuguharu Foujita (1886-1968), David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896-1974) or A. Riganelli. These works have contributed to freeze M. C. Portela’s energy and momentum, confining her to the traditional place of muse. Even her friend Rafael Alberti, a noted Spanish poet and art critic who was exiled in Argentina, wrote about her not only as an artist, but also as a muse for inspired painters.6

But M. C. Portela reclaimed her own image in several drypoints, some made in the last years of her life. One of these self-portraits explores her facial features unapologetically and renders visible the effects of time on M. C. Portela’s celebrated beauty. By presenting herself as a mature and wise woman, she helped to diversify the ways in which women are exhibited in visual culture.

Gluzman Georgina G., “María Carmen Portela. Una artista de múltiples rupturas”, Ñ, 13 October, 2018, p. 31.

2

On Los Artistas del Pueblo, see Miguel Ángel Muñoz, Los Artistas del Pueblo, Buenos Aires, Fundación OSDE, 2008.

3

Barrancos Dora, Mujeres en la sociedad argentina: una historia de cinco siglos, Buenos Aires, Sudamericana, 2010, pp. 155-156

4

“Una Buena Obra”, Crítica, September 1933, María Carmen Portela papers, private collection.

5

González Tuñon Raúl, “Carmen”, Contra, July, 1933, p. 9.

6

Alberti Rafael, María Carmen Portela, Buenos Aires, Losada, 1956, p. 10.

Georgina G. Gluzman (born in 1984, in Buenos Aires) is a Tenured Researcher at the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (National Scientific and Technical Research Council) in Argentina. She received her PhD in art history from the Universidad de Buenos Aires in 2015, having previously graduated with a degree in art history at the same university. G. G. Gluzman’s work focuses on the art of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Argentine women artists. She is the author of Trazos invisibles: Mujeres artistas en Buenos Aires (1890-1923), published in 2016.

Georgina G. Gluzman, "María Carmen Portela: art, politics, new women, and social commitment." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/maria-carmen-portela-art-politique-nouvelles-femmes-et-engagement-social/. Accessed 16 July 2025