Svensson Ana Maria and Rousseau Pascal, Hilma af Klint, une modernité révélée, exh. cat., Centre Culturel Suédois, Paris, (10 April–27 July 2008), Paris, Centre Culturel Suédois, 2008

→Müller-Westermann Iris et Widoff Jo (ed.), Hilma Af Klint: A Pioneer of Abstraction, exh. cat., Moderna Museet, Stockholm; Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum fur Gegenwart, Berlin; Museo Picasso Málaga, Málaga, (2013-2015), Berlin, Hatje Cantz, 2013

Hilma af Klint, une modernité révélée, Centre Culturel Suédois, Paris, 10 April–27 July 2008

Swedish painter.

It was not until 1986, with the exhibition The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985 at the Los Angeles Museum of Art, that Hilma af Klint’s work was finally acknowledged in art history and by the general public. Her paintings were shown alongside those of Mondrian, Wassily Kandinsky and Kazimir Malevich, but when one looks at the dates of her first abstract works, it appears that the painter was in fact ahead of her time and could not have been influenced by artists considered as pioneers in the field of abstract art. Her solitary and unusual career is strongly related to a spiritual and esoteric development. Only a small group of insiders was aware of her “mystical” paintings, and the artist herself was convinced that the general public was unable to understand them. Botany and mathematics were major interests in her family, and she spent her summers at a manor near Mälaren Lake, close to Stockholm, where the beauty of nature undeniably affected her artistic orientation. She studied at the Technical Art School in Stockholm around 1880, then at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts from 1882 to 1887. Her main production at the time consisted in landscapes and portraits (Utsikt över Mälaren, “View of Lake Mälaren”, 1903) that displayed the typical tastes of her times.

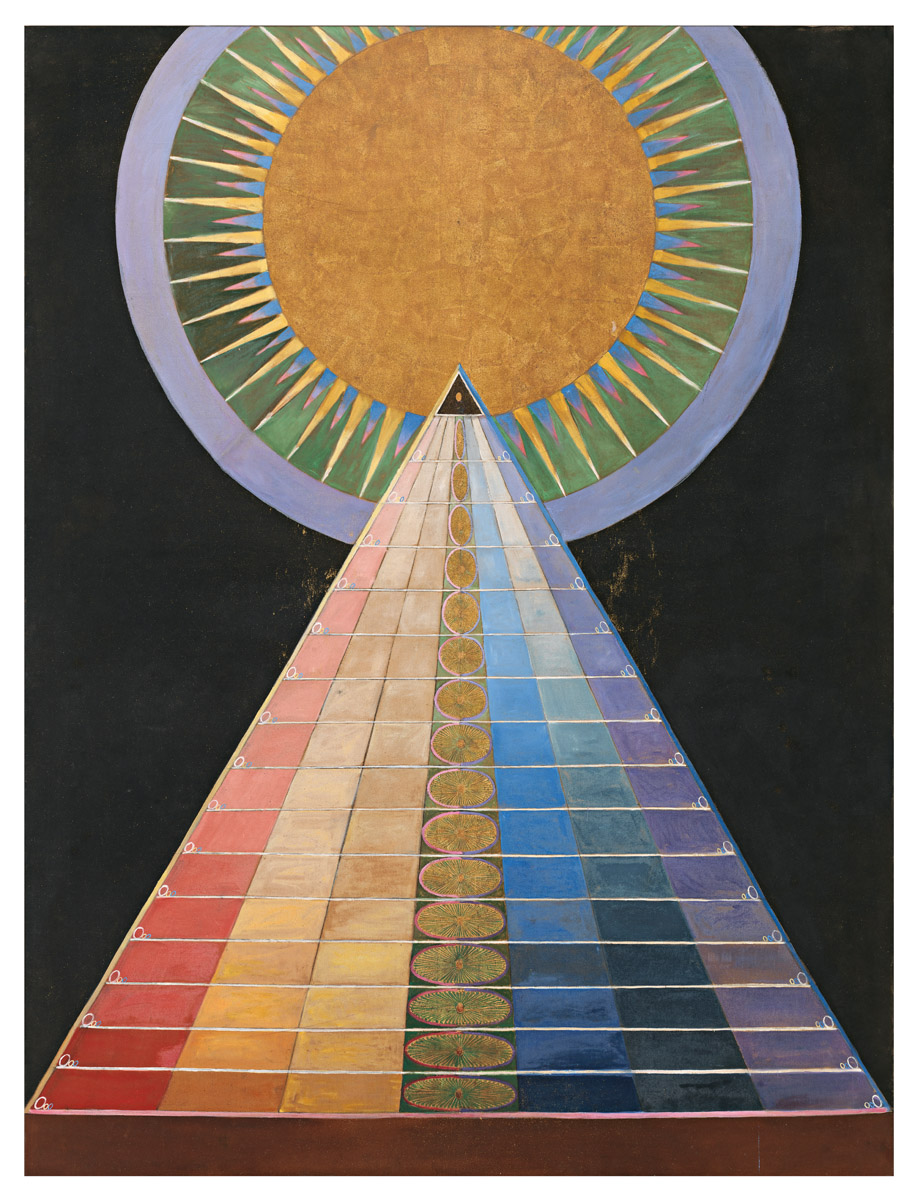

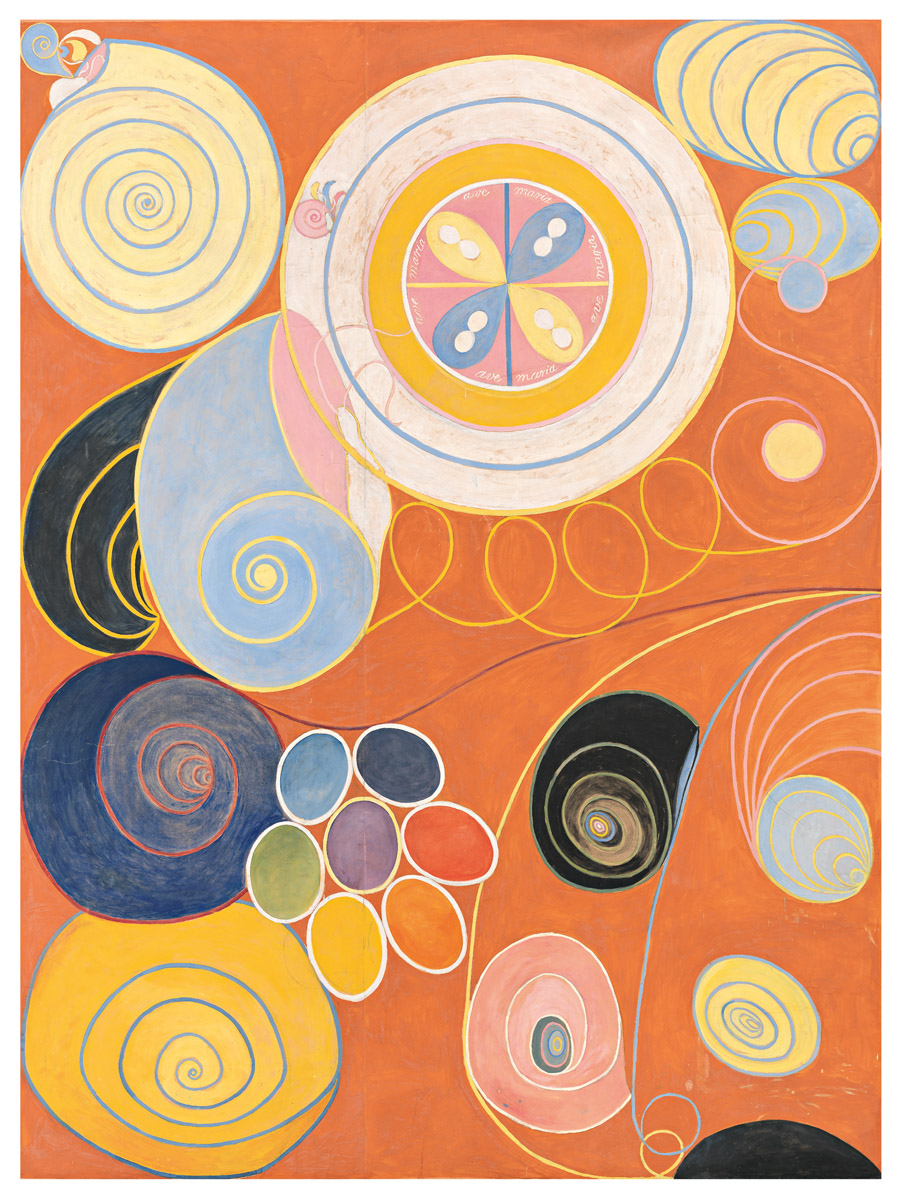

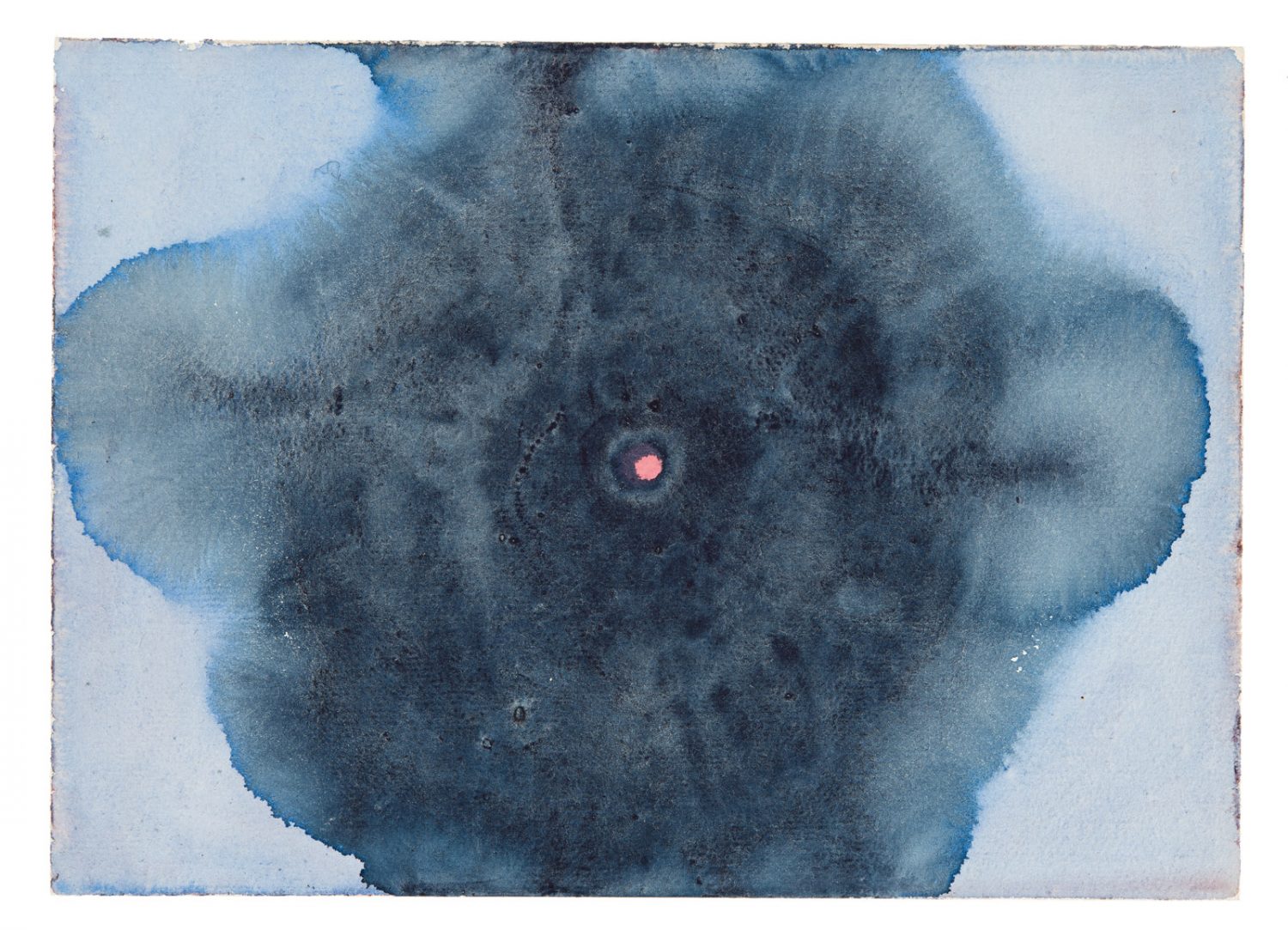

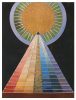

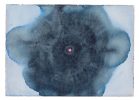

For twenty years her painting followed these academic lines, with no knowledge of European avant-garde movements. Then in 1906, under the influence of the highly successful Theosophical movement founded by the Russian Helena Blavatsky (1831-1891), she became fascinated by psychic phenomena and, with four other women artists, founded the esoteric group De fem (“The Five”). During their séances, a spirit called Amaliel requested her to paint a series of pictures, prompting the series Målningarna till Templet [“paintings for the temple”]. Painted following a psychic – i.e. automatic – method, and sometimes in a state of trance, this work was carried out from 1906 to 1908, and from 1912 to 1915. It contains over 190 pictures and is organised in various groups of paintings, among which the series WU [“the rose”] and De Tio Största [“the ten largest”], all of which express a search for harmony based on the opposition of contradictory principles: the male-female body is a metaphor of the divide between spiritual life (symbolised by the letter “U”) and material life (symbolised by the “W”); likewise, the colour blue is used for women and yellow for men. In 1916, one year after completing her work, she had a studio specially built on an island near Stockholm to exhibit the “mystical” series to a selected number of people. In addition to this creative output, she continued to present academic work from 1910 to 1914, for purely financial reasons, at exhibitions organised by the Association of Swedish women painters, which she was part of. In 1914 she showed portraits and landscapes at the Baltic Exhibition in Malmö, where Kandinsky showed abstract paintings. From 1916 to 1920 she continued her research on the astral world, which led hear to a form of pure abstraction, as can be seen in her memorable series from this period, Percival (1916) and The Atom (1917).

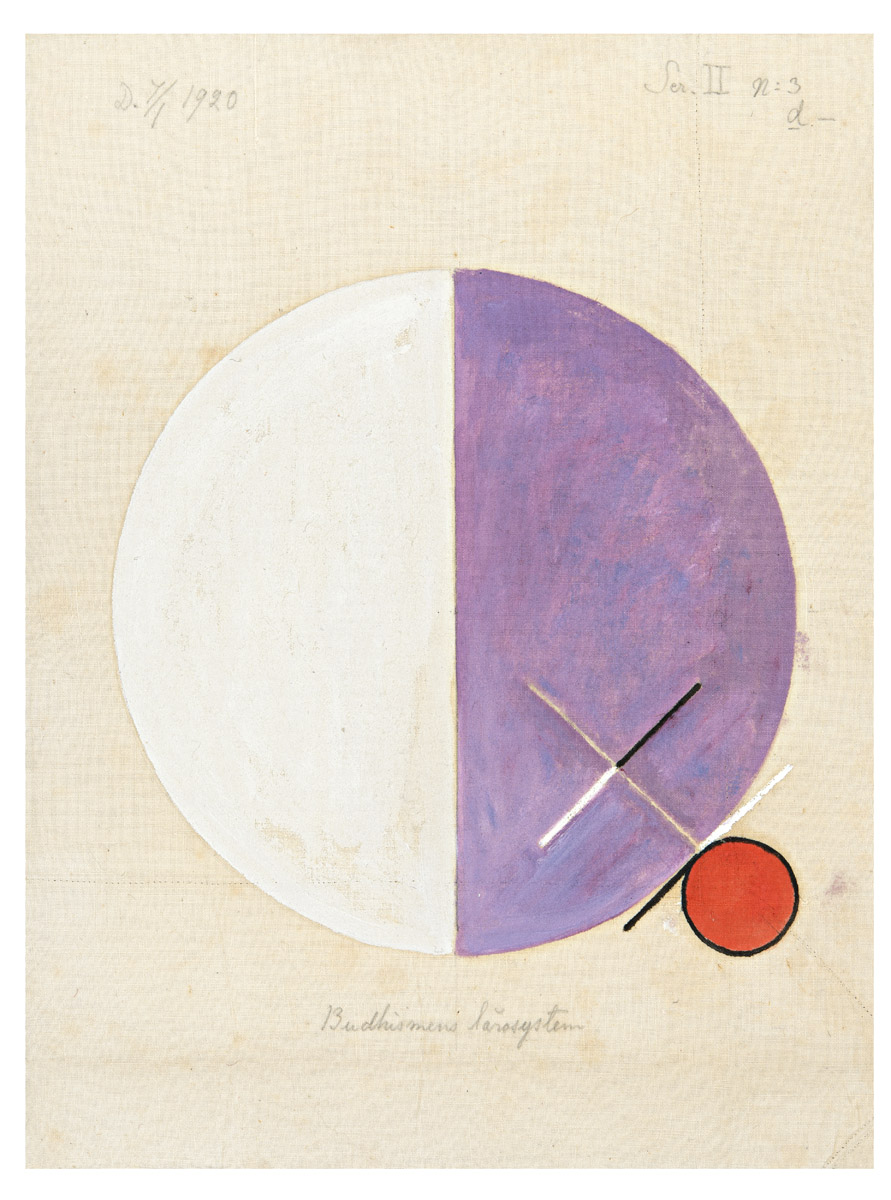

After her mother died in 1920, she moved to Helsingborg and became fascinated by the thoughts of Rudolf Steiner, founder and leader of the Anthroposophical Society since 1912. As a result, she spent the next two decades painting small-format watercolours, both figurative and non-figurative. When she died, she left behind a considerable body of work of over 1,000 pieces, which she left to her nephew Erik af Klint, on condition that he wait twenty years before exhibiting them. However, only forty years after her death did the public finally discover the scope and extraordinary modernity of her abstract work, which allows for a reassessment of the birth of abstraction in European art history. A foundation is devoted to her work in Stockholm. In 2008, her work was given major exposure at the exhibition Traces du sacré at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Moderna Museet Stockholm devoted the exhibition Hilma af Klint: A Pioneer of Abstraction to her in 2013.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

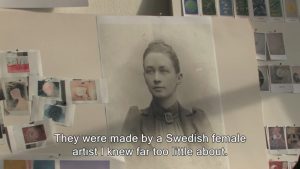

Iris Müller-Westermann (Moderna Museet) presents Hilma af Klint

Iris Müller-Westermann (Moderna Museet) presents Hilma af Klint