Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing. Femmes, de l’enfance a la vieillesse, 1929-1955, Paris, Éditions des femmes, 1982

→Reynaud Françoise, Barrett Nancy, Sougez Emmanuel (ed.), Ilse Bing. Paris, 1931-1952, exh. cat., Musée Carnavalet, Paris (1 December 1987–31 January 1988), Paris, Paris Musées/Musée Carnavalet, 1997

→Dryansky Larisa, Houk Edwynn, Ilse Bing: Photography Through the Looking Glass, New York, Harry N. Abrams, 2006

Ilse Bing. Femmes, de l’enfance a la vieillesse, 1929-1955, Galerie des Femmes, Paris, 1982

→Ilse Bing. Paris, 1931-1952, Musée Carnavalet, Paris, 1 December 1987–31 January 1988

→The Ilse Bing: Queen of the Leica, Victoria and Albert’s Museum, London, 7 October 2004–9 January 2005

Photographe allemande.

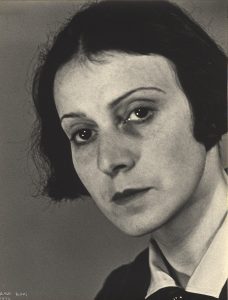

Nicknamed the Queen of Leica in the 1930s, Ilse Bing was an avant-garde photographer and photojournalism pioneer. Similar to Bauhaus in her abstraction, to Surrealism in her poetry, and to the modernist movement Nouvelle Vision in her attention to geometry, her work includes both portraits and fashion, architecture, and landscape photography. Along with her fellow-photographers Brassaï, Man Ray, Florence Henri, and Dora Maar, she contributed to making Paris the capital of photography in the 30s.

After studying mathematics and art history in Frankfurt and Vienna, she took up photography in 1923. She started out as a photojournalist and quickly made a name for herself in the press and illustrated magazines, including Frankfurter Illustrierte in 1929. According to the photographer Gisèle Freund, what persuaded Bing to move to Paris in 1930 were F. Henri’s photographs. Upon arriving in Paris, the young woman was quickly recognised by the avant-garde circles. Her pictures were exhibited and published in many magazines, such as Vu, Arts et métiers graphiques, L’Art vivant, and Harper’s Bazaar, placing her at the heart of the golden age of illustrated magazines.

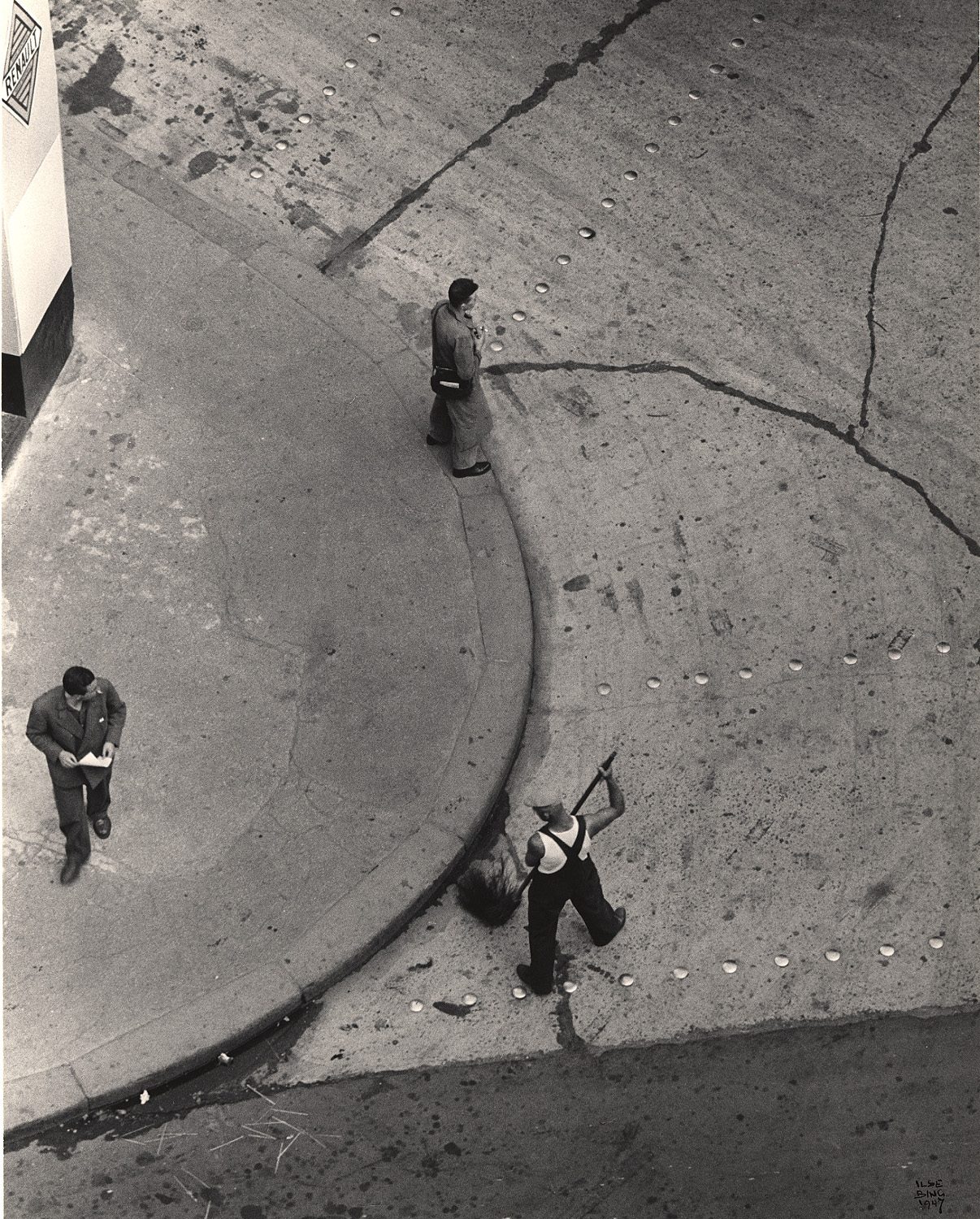

Using exclusively a small Leica, she worked on modernist motifs – geometrical and industrial landscapes, railways, stations. Some of her pictures, especially those of the Eiffel Tower (1931), with their metallic motifs and striking camera angles, are reminiscent of Germaine Krull and the Nouvelle Vision movement. Paris, Windows With Flags, Bastille Day (1933) also plays on the geometrical repetition of the windows and tricolour flags. Her Parisian period is also marked by a strong dreamlike quality – the whirling dancers at the Moulin-Rouge (French Can-can Dancers series, Paris, 1931) and nostalgic poetry found in the multitude of small details she encountered. Her close-ups of the Alexander III Bridge (1935) and of chairs in Parisian parks, puddles of water, and shop signs (Boucherie chevaline [Horse-meat Butcher’s], 1933), develop a vision that restores the enchanted facet of Paris through its particularities, a method also developed by the Surrealists at the time. The photographer also tried her hand at experimental photography, with solarisations of Parisian fountains (Place de la Concorde and Rond-Point des Champs-Élysées, 1934), and dance photography (Ballet Errante, 1933).

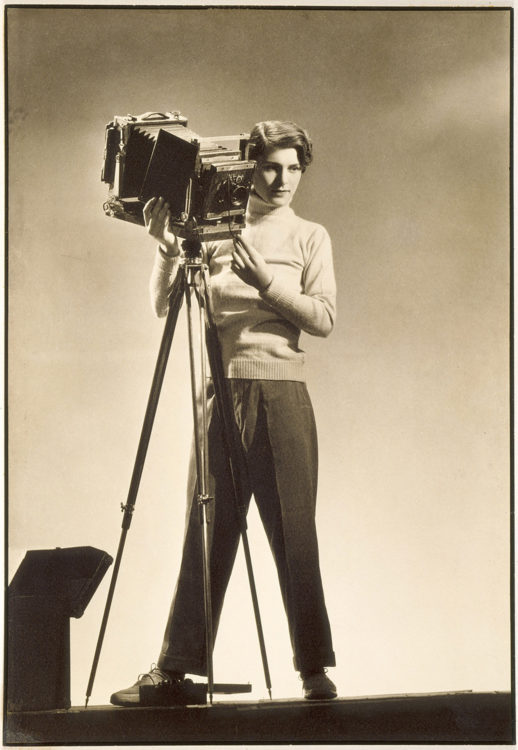

Her most famous photograph, Self-Portrait With Leica (1931), can be interpreted as a symbol. In this picture, the artist designates herself as the central figure of the historic moment that the 1930s were for photography, and makes the Leica a character in its own right. This cult, portable and lightweight device was the symbol of modernism; its user-friendliness made it an embodiment of the extension of the eye and revolutionised photography. It served the modern conception of photography as the art of capturing images in the flow of reality. This conception was shared in part by the artist, for whom the camera constituted a way of breaking the boundary between dreams and reality, and of capturing snatches of fantasy and imagination in the real world. The photographer is particularly marked by the world of childhood and fantasy, as is visible in the many pictures she took of festivals and fairgrounds. In 1940, Ilse Bing, a German Jew, was detained at the Pyrenean concentration camp of Gurs, waiting for an American visa. She fled to New York in 1941 and resumed her work as a photographer. But the start of her second career proved difficult, with financial troubles even forcing her to work at a dog-grooming parlour. In 1959, she put an end to her professional photography career and started making experimental compositions with an 8mm colour Bolex. She began writing poetry and drawing in 1968 and published two books, Words as Vision (1974) and Numbers in Images (1976). Forgotten for almost two decades, her work was rediscovered in the late 70s, when photography became recognised on the international scene. A few of her works were shown in New York at MoMA in 1976, where they came to the public’s attention, then at the Witkin Gallery. In 1982, she published her first book of photographs, Femmes de l’enfance à la vieillesse (Women from the Cradle to Old Age), with a preface by Gisèle Freund. Her crucial position in the history of photography makes her the embodiment of the modernist turning point and the Leica revolution, as well as a symbol of the birth of a new and essential figure of the interwar period: the woman photographer.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Ilse Bing Top # 11 Facts

Ilse Bing Top # 11 Facts