Isa Genzken

Diederichsen Diedrich & Farquharson Alex, Isa Genzken, London/New York, Phaidon, 2006

→Ruf Beatrix (ed.), Isa Genzken: I love New York, crazy city, Zurich, JRP Ringier, 2006

Isa Genzken: Sie sind mein Glück, Kunstverein Braunschweig, 11 June – 27 August 2000

→Isa Genzken: Open, Sesame!, Whitechapel Gallery, London; Museum Ludwig, Cologne, 2009 – 2010

→Isa Genzken: retrospective, The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Chicago, Museum of Contemporary Art; Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, 2013 – 2015

Plasticienne allemande.

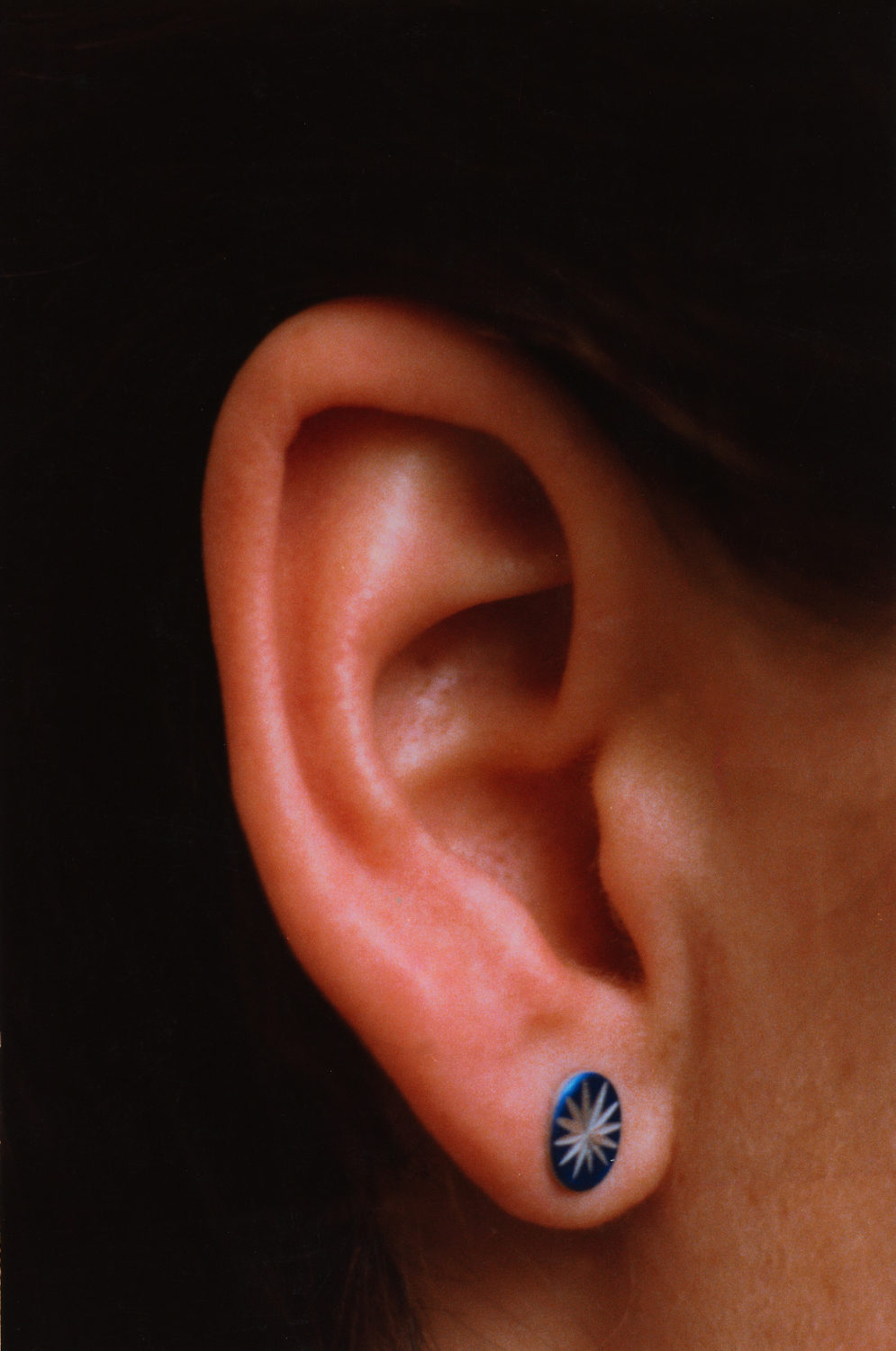

It took several decades for Isa Genzken’s pieces (sculptures, installations, photographs, paintings, and collages) to be recognized among the most important contributions to the history and renaissance of late-twentieth century sculpture. Composed of contemporary materials assembled in a sophisticated manner, her creations nonetheless display certain artisanal qualities. Her themes question the relationship between private and public space, the autonomy of art, and the collective experience. From a socio-political point of view, her forms demonstrate how art can find a way to bring shape and life to thought, ideology, and to humanity, its representations and disasters. The issue of material is of paramount importance to the artist. In the 1980s, she used wood, plaster, and concrete in her freestanding sculptures, which stand between 5 and 10 metres tall and call into question the architecture that was then at the heart of the postmodern debate over “deconstruction”. These conceptual objects are built following a rectangular design, enclosing space inside concrete walls without windows, fragments of architecture placed on a steel base (Marcel, 1987). In the 1990s, she introduced light and transparency, first using epoxy resin, a translucent material, then turning to coloured industrial glass, which lends her pieces a strange aesthetic. The façade becomes her subject, as in the New Buildings for Berlin series (2001–2002), a fragile incarnation of the skyscraper, made of glass, erected and grouped according to triangular and rectangular designs.

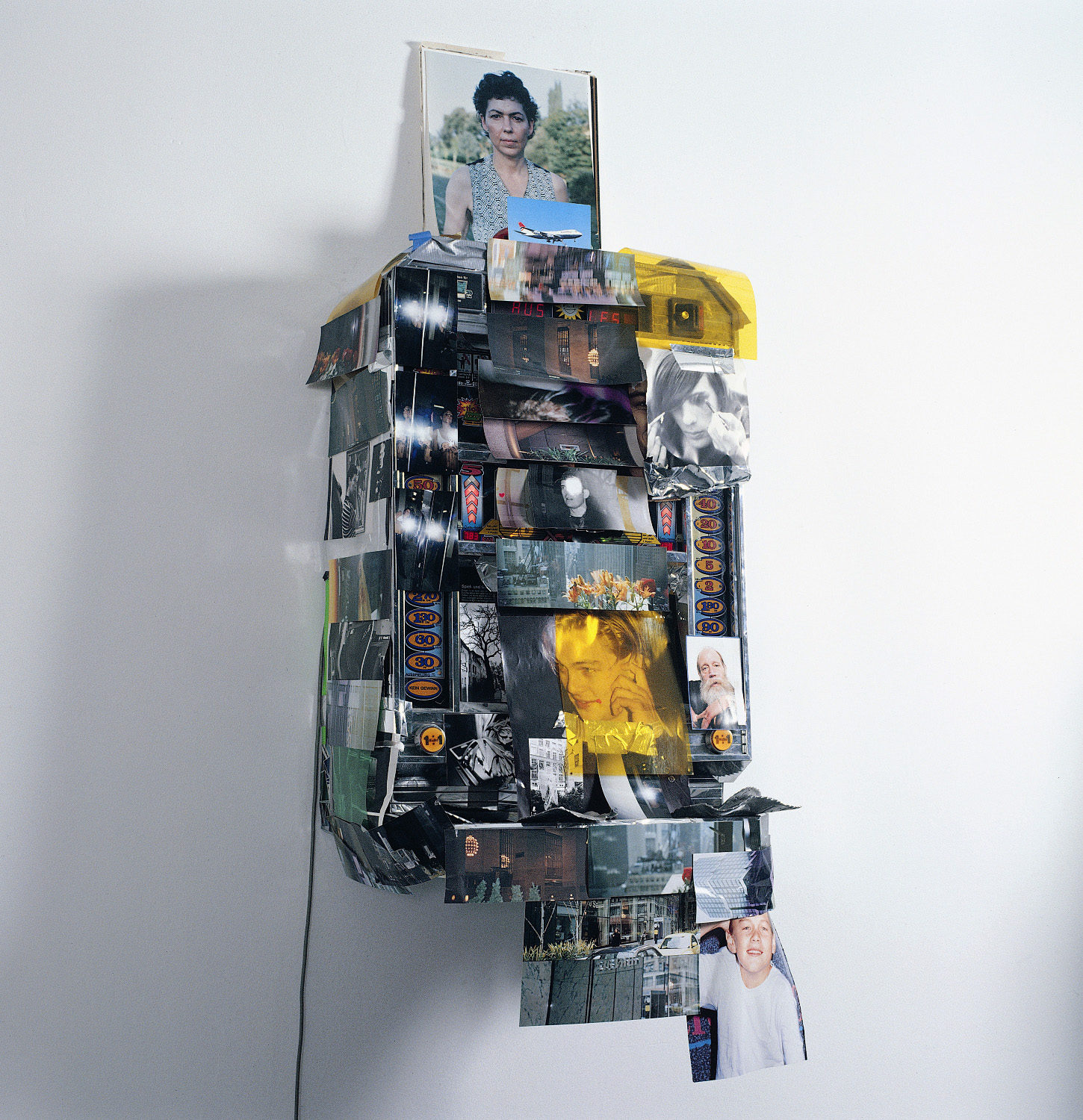

Then came, in the 2000s, the Social Façade series, in which the artist employed a format normally associated with painting. Strips of diverse metals – from copper plates to aluminium sheets – are glued to rectangular frames. Light, refracted by prisms onto shimmering surfaces, mirrors and multiplies the observer’s image, ego, and devastating power. This incursion took on even greater dimensions in the set of 22 sculptures entitled Empire Vampire, Who Kills Death (2002–2003), created following the September 11 attacks in 2001, which I. Genzken herself witnessed in New York. The materials became dirtier, and included plastic toys and debris; the colourless forms seem to be covered in ash, evoking the impenetrable and grey cloud that hung over the world that day. For a few years now, her installations have become more complex: they employ recycled materials, bright colours, torn and decomposed images, providing a feeling of violence, a definitive break with the idea of art as an all-encompassing discourse. Her exhibition in 2010 at the Chantal Crousel Gallery in Paris is a testament to this; she presented, namely, Mona Isa, which featured iconic characters from the history of art, such as Leonardo da Vinci or Michael Jackson, next to her own portraits. In Hotel, Harfe, Ambulance, Nofretete, Bibliothek (2010), sculpture-bodies symbolize universal lifestyle, in Lautsprecher, empty speaker cabinets, receivers or transmitters suspended from the ceiling forever await sounds, and an elephant – that big, sad, and tired animal – enters the exhibition through a hidden window (Mona Isa III [Elefant], 2010). The international public discovered her in 2007 through the Venice Biennale, where Genzken showcased the opaque and reflective dimensions of the history of the German pavilion, creating a real metamorphosis of and about architecture, a place where glamour and misery, euphoria and disillusion, the popular idea and the collapse of modernism rub shoulders. The MoMA devoted an important retrospective to her work in 2013.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2019

This is Isa Genzken at MoMA

This is Isa Genzken at MoMA