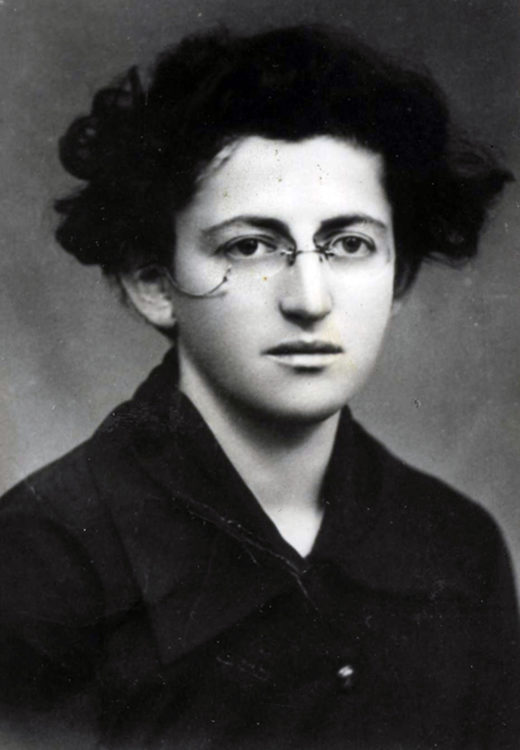

Juana Muller

Dubbeld Sabrina, Juana Muller, 1911-1952, destin d’une femme sculpteur, Paris, Somogy, 2015

→Autour de Juana Muller, sculptrices et peintres à Paris 1940/1960, exh. cat., Maison des Arts, Antony (15 April – 12 June 2016), Antony, Maison des Arts, 2016

La femme dans l’art, Museo Nacional de Balles Artes, Santiago, September 1975

→Juana Muller, 1911-1952, Musée d’Art et d’Histoire de la ville de Meudon, Meudon, 6 January – 19 February 1984

→Sculpture’Elles, Les Sculpteurs femmes du XVIIIe siècle à nos jours, Musée des Années 30, Boulogne-Billancourt, 12 May – 2 October 2011

Chilean sculptor.

From 1930 to 1933, Juana Muller studied at the Escuela de Bellas Artes de Santiago with Julio Antonia Vásquez (1897–1976), followed by Lorenzo Domínquez (1901–1963). Only rare photographs of her head and bust sculptures remain from these formative years, illustrating the sharp choices of an artist who manifested an early attraction for the female figure. The excellent performance of J. Muller culminated in her receipt of a scholarship in 1937 that allowed her to go to France. Upon her arrival in Paris, she prolonged her apprenticeship under Ossip Zadkine (1888–1967), who directed the sculptor studio at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. She frequented the Académie Ranson, where she met the painter Jean Le Moal (1909–2007), whom she married in 1944. It was during this time, likely in 1938–1939, that she met Constantin Brancusi (1876–1957) – a pivotal moment in her career – with whom she formed a fruitful friendship witnessed in their copious correspondence preserved today at the Bibliothèque Kandinsky. Brancusi immediately took her under his wing, sharing with her his studio secrets and his opinions about art, philosophy and spirituality. He solicited her aid for the realisation of La Tortue volante (1940–1945) – the ultimate proof of his trust in her.

After J. Muller moved to Brancusi’s studio, located in the Impasse Ronsin in Paris, her production transformed: the formats became more imposing, the materials (wood, stone, earthenware) and techniques more diverse, while her works detached themselves little by little from figuration. Her portraits (1930–1950), one of her favoured themes, gradually lost their naturalistic details, gaining a certain universality. Their serene beauty attracted the attention of Henri Pierre Roché, whose appetite for carved faces of women with captivating features never dwindled. In a text published on the occasion of a group exhibition organised at the gallery MAI in 1952 – in which J. Muller participated alongside Etienne-Martin (1913–1995), François Stahly (1911–2006) and Marie-Thérèse Pinto (1894–1980) – H. Roché stated that, “her Tête pour un tombeau (Head for a grave), with its wide eyes, and her pouting Cariatide énimatique (Enigmatic caryatid) with droopy eyelids, gave a silencing presence.”

In post-war Paris, the sculptor found herself at the centre of the artistic trends. She spent time with the artists united under the name of the “Nouvelle École de Paris,” including Jean Bertholle, Jean Bazaine, Alfred Manessier, Pierre Tal Coat, Gustave Singier, Vera Pagava, Alicia Penalba (1913–1982), Marta Colvin (1907–1995) and M.-T. Pinto. Her work was supported by the galleries Jeanne Bucher and Folklore, and she exhibited regularly at the Salon de Mai (May Salon) and the Salon de la jeune sculpture (Young Sculpture Salon). Her dispatches were noticed, particularly her Totem series, begun in 1945 and continued until her death. A true axis mundi, these works maintained close links to architecture through their contained monumentality. As the artist wrote, it is because “architecture and sculpture must form a unity that results from an idea that would be the basis of all human activity.” Moved by the desire to reconnect with the utopia of cathedral builders, the artist devoted her energy to the decoration project of the new church Saint-Remy de Baccart in Meurthe-et-Moselle, creating several studies of liturgical furniture and sketches for a sculpture of the Way of the Cross between 1950 and 1952.